How Sheikh Hasina Fell: The Story of Bangladesh’s July Revolution

When the British historian AJP Taylor wrote that in 1848 “German history reached its turning-point and failed to turn”, he was speaking not of crowds or courage, but of consequences. Germany’s liberal revolts had barricades, manifestos, and youthful idealism in abundance. What they lacked was a durable transformation of power. Old elites regrouped, authority reasserted itself, and history moved—just not in the direction the revolutionaries had imagined. Taylor’s remark has since become a warning against mistaking political drama for structural change.

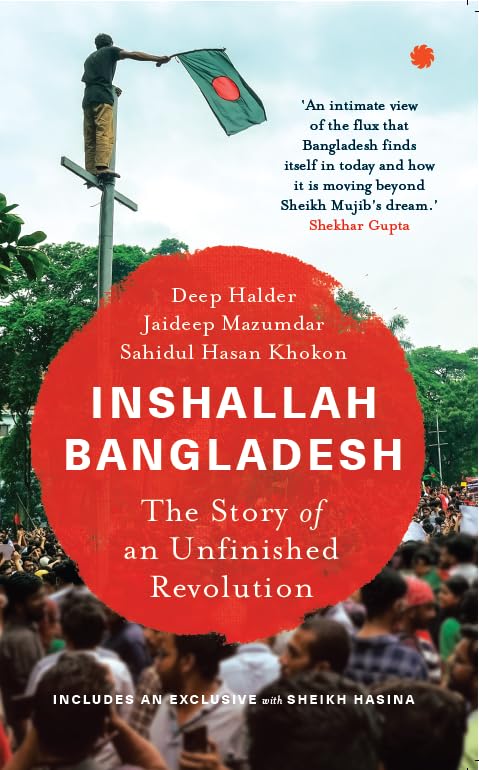

Reading Inshallah Bangladesh: The Story of an Unfinished Revolution (2025), it is difficult not to hear the echo of that warning. The book captures a moment of extraordinary intensity, otherwise known as the July Revolution (2024): a students’ protest spiralling into a nationwide uprising, a long-entrenched prime minister fleeing the country, and the ruling party that once embodied the spirit of 1971—when the Liberation War took place—suddenly outlawed and disgraced. For a few heady weeks, Bangladesh appeared to stand at a decisive crossroads.

Written by Deep Halder, Jaideep Mazumdar and Sahidul Hasan Khokon, Inshallah Bangladesh brings together three journalists with long experience of South Asian politics, conflict reporting, and Bangladesh’s fraught public sphere. This background matters. The book is not an exercise in retrospective theorising, nor does it indulge in ideological polemic.

The book reads at times like reportage and at other times like a political thriller, with explosive new details that make familiar headlines feel newly strange. One of the most compelling episodes the authors reconstruct is the closing hours of Sheikh Hasina’s rule. On August 5, 2024, as protestors converged on Dhaka and security forces hesitated, Hasina received a phone call at 1.30PM from a top Indian official she knew well.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

According to the book, this minute-long exchange was decisive—and may have saved her life. Inshallah Bangladesh recounts how Hasina initially refused military advice to flee, confident that state coercive power would hold. It was only after the India call—urging her to “live to fight another day”—that she agreed to evacuate Ganabhaban, the prime minister’s residence, and escape by helicopter before boarding a C-130 transport to India. Within hours, she was in secure New Delhi, escorted by India’s National Security Advisor.

The Importance of the Perspective

The book implicitly shows that Hasina did not leave because a revolution demanded it; she left because the state could no longer guarantee her survival. Few accounts of South Asian political upheaval have captured this twilight zone between command and collapse with such precision.

Equally important is the book’s refusal to reduce the uprising to a single cause or constituency. While students dominate the opening chapters, the authors quickly widen the frame to include lawyers, journalists, civil servants, informal workers, and families of security personnel. The protests are shown not as a homogeneous moral community but as a convergence of grievances, some overlapping, others contradictory. From the outset, Inshallah Bangladesh is written as a chronicle of destabilisation, not deliverance.

What immediately distinguishes Inshallah Bangladesh from routine political commentary is its narrative texture. The book opens like a thriller. A journalist in Dhaka receives a chilling phone call from a military intelligence officer: “Run before it’s too late. There is no law left”. From there, the story unfolds through scenes of escalating chaos—ambulances ferrying mutilated policemen, mobs roaming neighbourhoods, security forces unsure of their own chain of command.

The authors reconstruct these moments with the instincts of seasoned reporters, relying on eyewitness testimony, internal security briefings, and conversations with political actors across factions. Dhaka’s descent into disorder is rendered not as abstraction but as lived experience, where authority dissolves not with a proclamation but with hesitation.

These scenes do more than add colour. They underscore a central, if understated, argument of the book: that the fall of the Hasina regime was not simply the result of popular mobilisation, but of state paralysis at a critical juncture.

An Unfinished Revolution?

Yet, the book also documents something more unsettling: the deep distrust of India among young Bangladeshis, a sentiment that shaped both the uprising and its aftermath. Drawing on border testimonies, the authors recount incidents of violence involving India’s Border Security Force, including the harrowing account of a teenage boy wounded in a border encounter. These stories circulate widely among Bangladesh’s youth, feeding a narrative in which India is seen not as a benevolent ally of 1971 but as a domineering neighbour indifferent to Bangladeshi lives. In Inshallah Bangladesh, this distrust is not treated as propaganda or fringe sentiment; it is shown as a shared emotional reality that cuts across ideological lines and complicates any reading of the movement as purely domestic or liberal.

It is at this point that the book’s subtitle—An Unfinished Revolution—begins to feel less rhetorical and more diagnostic.

The authors repeatedly describe the upheaval as a student revolution, and there is no denying the centrality of campuses, youth networks, and student courage. But history offers little support for the idea that students alone make revolutions.

Revolutions succeed—or fail—based on what happens inside states. This is where the work of Theda Skocpol becomes quietly relevant. In States and Social Revolutions (1979), Skocpol argued that revolutions emerge not from ideology alone, but from structural breakdown—when administrative capacity erodes, elites fracture, and coercive institutions fail to act in unison. Popular mobilisation matters, but only when the state can no longer hold.

Seen through this lens, Inshallah Bangladesh reads less like the story of a pure student uprising and more like a case study in state failure. Police violence escalated and then lost effectiveness. Bureaucratic authority wavered. Most tellingly, the armed forces—under General Waker-Uz-Zaman—refused to intervene decisively, warning of catastrophic consequences if troops were ordered to fire. The fall of Sheikh Hasina, the book suggests through its own evidence, was contingent, not inevitable.

What followed reinforces this scepticism. If the events of July 2024 constituted a full-fledged social revolution, one would expect a decisive restructuring of power. Instead, Bangladesh entered a liminal phase. An interim government took charge. New parties mushroomed. Old opposition forces resurfaced. And most significantly, Islamist organisations re-entered the political arena with confidence.

The book does not exaggerate this development, but it does not ignore it either. To understand the re-entry of Islamist forces after Hasina’s exit, the book implicitly gestures towards a longer South Asian history of religion stepping into political vacuums left by exhausted secularisms. Bangladesh’s trajectory is not unique in this respect. From Pakistan after Ayub Khan, to Iran after the Shah, to Sri Lanka’s ethno-religious turn following the collapse of left-nationalist coalitions, moments of state weakening have often enabled religious actors to reorganise themselves as moral alternatives to discredited regimes.

Islamic Revivalism

The book is careful to show that Islamic revivalism in Bangladesh has never been merely theological. It has been institutional, pedagogical, and organisational. Student wings, mosque networks, welfare associations, and informal justice mechanisms had long existed beneath the surface of Hasina’s securitised secularism.

Bangladesh’s contradictions run deep. It was born in 1971 out of a secular, linguistic nationalism that deliberately distanced itself from the Islamic politics of its neighbours. And yet, Islam has never been absent from the country’s political imagination. It celebrates 1971 as a founding rupture, yet continues to wrestle with the legacies of Partition, Pakistan, and pan-Islamic politics. Even moments of apparent reconciliation, such as Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s visit to Dhaka in 1974 and his reception by Mujibur Rahman, underscored how layered and uneasy these identities were.

The book implicitly reminds readers that revolutions do not inherit the values of their initiators by default. They inherit the structures that survive the collapse. In Bangladesh’s case, those structures include religious organisations with deep roots, disciplined cadres, and a narrative of moral legitimacy sharpened by years of exclusion. Inshallah Bangladesh thus becomes not only a story of an uprising, but a meditation on what follows when secular authority erodes without being institutionally renewed.

Amid the weakening of the secular-authoritarian order that Hasina represented, groups like Jamaat-e-Islami moved swiftly to assert presence, mobilise supporters, and contest the meaning of Bangladesh’s future. Attacks on minorities, renewed religious rhetoric, and demands for constitutional reorientation appear in the narrative as warning signs. The irony is stark: a movement ignited by youthful, largely secular grievances risks empowering forces historically opposed to the secular foundations of the state.

What’s New? What’s Old?

Islamic political mobilisation in Bangladesh long predates the current crisis. From the dilution of secularism in the late 1970s to the rehabilitation of Jamaat into electoral politics, religious identity has always coexisted uneasily with Bengali nationalism. Hasina’s regime did not eliminate these forces; it suppressed them. And history teaches us that suppression does not erase political energies—it merely postpones their return.

Inshallah Bangladesh deserves attention precisely because it captures this moment of suspension. It does not offer easy conclusions, even if its narrative occasionally leans toward revolutionary affirmation. Its greatest strength lies in showing how rapidly history can accelerate, and how uncertain its destinations can be.

Whether Bangladesh’s turning point will eventually turn—or whether it will join the long list of aborted transformations—remains an open question. That uncertainty is not the book’s failure. It is the condition of the present.