Anuradha Bhagwati: ‘Women make incredible marksmen’

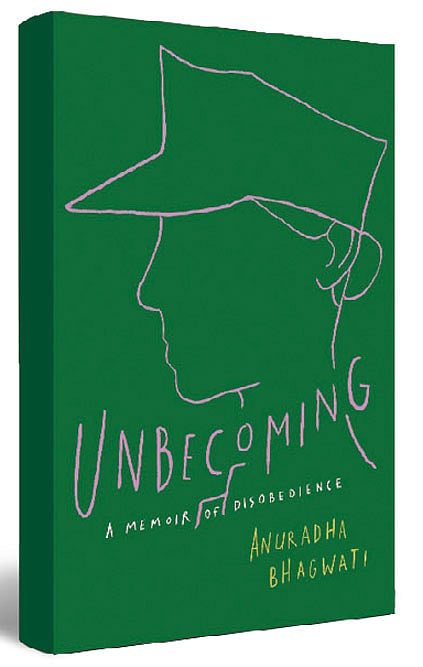

ANURADHA BHAGWATI’S memoir Unbecoming: A Memoir of Disobedience (Simon & Schuster; 321 pages; Rs 699) is an account of rebellion and reconciliation. Born in 1975 in Boston to renowned economist parents (Jagdish Bhagwati and Padma Desai), she spent her early years chafing against a family and society which did not understand her questioning and spirited self. With everything she had wanted to do being forbidden, she decided to abandon graduate school at Columbia University, where her parents taught, and chose to join the US Marines instead. Her memoir, published last year, is an account of being a ‘brown female activist’ in the most masculine of settings. In her writing, she anatomises her own actions and of those around her, with a steady surgeon’s hand. Once her service concluded in 2004, she founded Service Women’s Action Network, which brought attention to sexual violence in the military and helped repeal the ban on women in combat. Just days after India’s historic Supreme Court ruling—which makes women army officers eligible for permanent commissions, allowing them to be in commanding roles—Open caught up with the New York-based Marine Corps veteran who is also a yoga and meditation teacher and a flying trapeze acrobat. Excerpts:

What was your first response when you heard that women in the Indian military would be eligible for permanent commissions, allowing them to be in commanding roles?

I am thrilled. It is incredible. The most exciting thing is not just the ruling itself. But the tone of the judges. It was like, ‘You’ve got to be kidding, guys. This is just sexism pure and simple. You need to come up with a better argument to keep women from doing what they are clearly qualified to do. Stop making up these nonsensical arguments about men in rural areas not being able to follow orders.’ It was really exciting to read some of that.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The larger issue though, and the advocates pointed to this, is that India will have to go way farther than this. This is the first of many steps. Women have to have the opportunity to try out for any assignment, even combat assignments, anything short of that, is not good enough. The arguments are always the same—women are too weak, there wouldn’t be an order of discipline in the ranks, discipline will break down among men, there will be more sexual assault, all of these arguments have failed to have been proven true, they are not the reality on the battlefield.

I’ve worked closely with integrating women into the US military. I left the Marines. My organisation actually sued the Pentagon to open up combat assignments to women in the US armed forces. Thankfully, the US govt was ready to do the right thing.

The argument we would hear all the time is women wouldn’t want these jobs on the frontlines. My response is always, ‘Well some will. Many will not. Just as some men will, and many men will not.’ This is not about opening up all jobs to all women in the universe, it is about opening it up to any man or woman who is qualified for that job. Don’t lower standards. You have to create a single standard regardless of gender, religion, caste, race, anything. This is how militaries enforce discipline by making sure that there aren’t double standards, there isn’t special preference. India can do this.

You write how you quickly learnt that in Marine culture women appeared to have ‘two choices in the aftermath of a sexual violation; either act like nothing was wrong and play along, or suffer privately and keep quiet’. How does one begin to change this culture of silence?

For far too long it has been incumbent upon victims to speak up for themselves. Which is very unrealistic. Because often times victims are outnumbered, they are often intimidated, harassed by people who have more rank and power and authority. It is a very intimidating process to report harassment. To say nothing about the trauma you are probably going through as a result of the assault or harassment. It is really incumbent upon leadership and institutions themselves to train their officers, to train their enlisted leadership, to speak up on behalf of victims and enforce regulations. And not sweep allegations under the rug. And to believe victims and to prosecute predators. This is all very simple stuff. It is just law and order, about punishing the bad guys. Instead of punishing the offender they blame the woman or the man victim. There are many males who are victims of assault. It is about believing victims pure and simple. The pressure should not be put on victims to fix the problem, it should be on officer and managers who are managing those predators, those are the people who should be fixing this problem. We see very few sexual assaults are prosecuted in the military and that is a failure of military leadership to support victims.

You write how the MeToo movement of 2017 gave you some hope. Where do you think it is heading now?

I think it has done some extraordinary things for international consciousness. It is still fleshing itself out, so to speak. There is that demarcation, Before Weinstein and After Weinstein. I think one of the things that has happened is that more women are believing women. And that is one of the fundamental things that needs to change in our culture, whether it is Western or Eastern, it doesn’t matter. Oftentimes it is us who don’t believe one another, or support one another. People were sharing experiences they’ve never shared before. We need that in order to feel less alone. Then we can have the solidarity to come forward and do the difficult reporting of assault or harassment and seeing it through the system. It requires so much courage and patience and emotional resources, financial resources. This is not a short-term thing.

I have seen extraordinary progress. Men are also—good men—now much more conscious and thinking about what kind of language they should be using in the workplace, how they should be thinking about women they coexist with in the workplace, and how they treat partners, potential dates, the whole nine yards. A lot of this is generational. I have talked to many older men, they might not ever get it. But I have a lot of hope from the next generations of boys and men, I really do.

You write how ‘even good people could be trained to think and commit horrific, unthinkable acts of violence’. Similarly, aren’t ‘good men’ capable of sexual violence?

Ya. I mean within the military we learned that there is a group think. This is true for most institutions where toxic masculinity is allowed to go unchecked. This kind of bullying mentality, of ganging up on the weakest in the group, is so common, it is so hard to step out of the mould, whether you are a bystander, whether you are the victim, the perpetrator, everyone is involved in the culture of silence. The bystander is the one I am the most curious about. Because, really, how much can you do when you are being victimised? The perpetrator is oftentimes so stuck in their mind, it is hard to change their mindset. But the bystander oftentimes is just watching. They know this is wrong, yet they don’t act. And majority of the folk in these situations are bystanders. And so that is what is really disturbing. We join these institutions for a large part for honourable reasons. When bad things happen, we often don’t step up and help the people being harassed. That has to stop. And that requires having some skin in the game, and taking some risks. We have to learn to be better allies. It is not the job of the victim to speak up all the time. It is the job of the bystander to step up and be the friend. Which is what military leadership needs to train military personnel to do.

In the military, where you are trained to kill, how do you not have toxic masculinity?

It is very difficult to do in institutions where ethics are not part of the training. You have a lot of folks, unfortunately, who join the military around the world, who serve with this blood lust. This desire for violence, this desire to legally kill. Unfortunately, you do see a few sociopaths serving every now and then. But the vast majority are struggling with life and death circumstances, with doing the right thing. And most people do do the right thing, with good leadership. Where it gets really disturbing is when militaries instil troops with any kind of misogyny, any kind of racialised stereotyping, any kind of homophobia, any kind of othering of the civilian population. This is where things get really really messy.

I was really concerned after 9/11. In the West, we saw this rise in Islamophobia, and we are still seeing it, this racism against Brown people generally, Black people, people of other religions. Meanwhile we are sending troops around the world, and you know a handful of troops are blurting this very Islamophobic vocabulary and unfortunately committing crimes against civilian populations, because of this racism. This is nothing new. Exploitation of local women and girls, it will happen as long as military leadership sweep incidents under the rug, and pretend that all people who are going to serve are going to do the right thing. And we know that is not true as human beings are fallible.

In what ways does misogyny affect men?

I served mostly with men in the Marines. It is 93 per cent male. There is a sense in the civilian population, at least in the United States, that most people who serve are good and heroic. In general, I would like to think that. But there is so much misogyny in the training itself, in the culture itself. You can’t just walk out of it pretending that you haven’t benefited from it in some way. The treatment of women, I should say, the mistreatment of women is so glaringly obvious, to anyone who has their eyes open, it becomes so normalised after years of serving in uniform that I really had to reverse the indoctrination. And educate myself again about what kind of language is appropriate in a civil democratic kind of environment. What kind of attitudes were appropriate? And I was realisng my own misogyny. And I had grown up quite the proud women’s rights activist. I had to relearn how to be that way. Because sexism was part of our vocabulary, part of our pride, it was just unbelievable. It is hard to imagine that kind of culture. In the military the worst insult in the world is to be equated with a woman.

So few people speak out. We are taught to stay quiet in basic training and obey orders. It is almost in the DNA of your basic training. To speak out and actually go against the grain, it feels like you have to rewire your brain sometimes. Which is why so few people in the military speak out when racism, assault, happen.

You rewired your brain through yoga in a way?

In a way, yea. It is a long process. I still like to fight [laughs]. But the fight now is about social justice, ‘Why did they get away with that?’ Back when I was in training, there was definite blood lust. In boot camp and officer candidate school, I like to tell people, that killing is part of your daily philosophy. It is hard to imagine. When you are in basic training, there is a real tribal, primal instinct that is cultivated. You do everything in unison. You chant in unison. One of the words we used to chant in unison was ‘Kill’. And you say it in unison with dozens of other Marine candidates. So your drill instructor would tell you to stand, and you would stand, and then you scream at the top of your lungs, ‘Kill’. And then when you are ordered to sit down, you scream at the top of your lungs, ‘Kill’. When you run to grab your rifle, ‘Kill’, when you laced your boots, ‘Kill’. Dozens of times a day. And not just casually, we would say it like we were trying to wake up somebody across the ocean. And this is like day one. You don’t have a rank or commission and you are screaming ‘Kill’ at the top of your lungs all the time. It is really a reprogramming of the brain. It took me a decade to unlearn some of that language, because there is something really tribalistic and ancient about saying this stuff in unison, with all this passion, when you are wielding weapons. This is not peaceful training. It is very violent training. And so, I had to let it, like, go on a psychic level. Yoga and meditation have helped me with that because it is really hard mental training.

I found it interesting how much you like shooting and marksmanship.

It is funny to admit it, but it is a very meditative practice, aside from the recoil and the loud sound. I do feel like Buddhist monks [laughs]. It requires quieting of the mind, it is nothing but concentration, so yea, I do love these ultra-discipline, ultra-focus activities. Women make incredible marksmen. I remember guys with me would be so alarmed and surprised when women could shoot. I would be like, ‘Why are you surprised at that? What is wrong with you?’

You have this interesting line: ‘I wasn’t sure if I was the one holding the weapon, or the one looking into its muzzle.’

It is the world we live in. America fights a lot of wars. But most of the wars have been fought against people who look like me, in places in the Global South. It is hard to know sometimes when so-called ‘enemy combatants’, or ‘terrorists’, or use whatever word you like, look like your dad and mom. In fact, the more journalists and historians reveal the way wars have panned out through the ages, we see many folks on the other side are civilians, not enemy combatants. It is really difficult, knowing who is holding the weapon, who is at the receiving end of the weapon, it is dictated by power and money.

What is it like to be Brown in the US army? After all, patriotism is the bedrock of all armies. It is rather complicated, no?

It is a very complicated relationship. And one of the brilliant things about military training, in a place like the United States, where people do really come from all parts of the world, ethnicities, races, religions, it is so effective in its indoctrination. Ultimately, I just saw myself as a Marine, I was like, ‘I am just like everybody else.’ I believed it, ‘I am a Marine first and foremost, nothing else matters.’ And yet I experienced the misogyny and racism.

The scary thing now with the rise of this President and the rise of neo-Nazi groups, is that White supremacy is out in the open. Definitely when I was in the military it was behind closed doors. Now it is alive, well, out and proud. You see the rise of White nationalist groups in the military, you also see military leaders trying to clamp down on that, because that can get really dangerous, really fast.

What was it like writing this book? Especially parts on your parents, that must have been rather wrenching?

It was really a traumatic experience. I don’t think I knew what I was getting into when I started the project. It was harrowing. Many people would ask me when I was done, ‘Oh, it must have been such a cathartic experience.’ I would just laugh at them. There was nothing cathartic about it [laughs]. It is not like going on a juice cleanse. I learned a lot about trauma and memory, and what I was okay diving into, and what I was not okay diving into. I had to wrestle with how I’d tell the stories of people I care about. Is there an appropriate way to it? Is there not an appropriate way to do it all? Is it for me to tell? Them to tell? No one to tell? I learned so much about myself and boundaries and lines.

It is not for everyone, though, writing a trauma memoir, I would not recommend it. It is a reckoning.

What hobbies keep you busy now?

If I had not joined the military, I think I would have joined the circus and started a restaurant.

The circus?

Yes. I discovered flying trapeze a few years ago. It is amazing. I highly recommend it. Now I mostly open water swim. Cold water swimming during the winter, it is quite an adventure. In Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, with a Russian community. We swim on the weekends. Without wetsuits. Just in bikinis or trunks. And it is freezing. It is a wild spiritual experience, you feel like you are on fire, you are dying, you have to survive, so you have to swim, or your body will shut down in a hypothermic blaze [laughs]. You swim for like two minutes and then shiver on the beach for a few hours drinking hot tea. It is quite an experience. It is the weirdest thing I have ever done.

Sounds kinda crazy!

This is what happens when you leave the military, trying to find the most extreme things you can semi-safely do without completely destroying your body.