Sex and the Raj

IN INDIA’S IMAGINATION, the notion of sex and queer love had always been vast and unembarrassed—carved into stone, sung in verse. Its art and mythology spoke a language of sensuality.

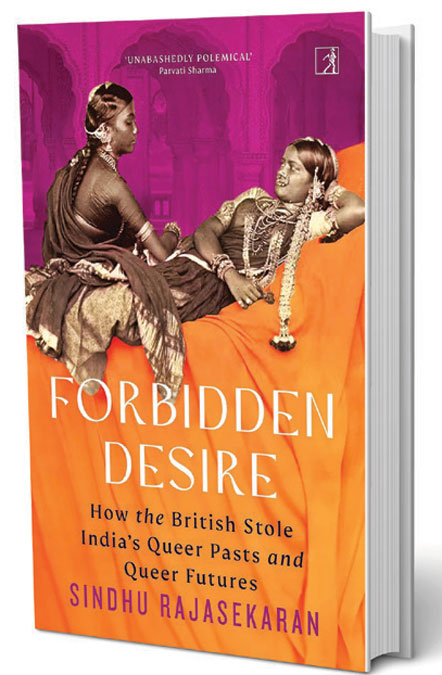

This changed under colonial rule, when the British imported their Victorian anxieties about sex and morality. Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, enacted in 1861 but later struck down in 2018, was the clearest expression of that discomfort, criminalising what had once been celebrated in story and sculpture. In her new book, Forbidden Desire: How the British Stole India’s Queer Pasts and Queer Futures, writer and academic Sindhu Rajasekaran traces this dramatic shift and its consequences on India’s attitude towards love and queerness.

In pre-colonial India, the boundaries between gender, sexuality and faith were porous. It was part of the fabric of life, not something to be hidden or policed. To recover this forgotten ease, Rajasekaran turns to literary and historical sources that speak of a culture once unafraid of its own complexity. That confidence began to erode after 1857, as British rule tightened its hold on India. With it came Victorian ideals of morality—repression disguised as virtue, and shame as civility—gradually remaking India’s moral imagination.

Rajasekaran, whose works include Smashing the Patriarchy, has studied this area for years. Growing up as a queer teenager in India, Rajasekaran’s account is also intensely personal. She describes the effects of Section 377 on her life as a 16-year-old. “I was scorned at, marked as a sexual deviant… Everyone cited Section 377. I was told I was a criminal for being in love. It was traumatic.”

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

“All love is queer love in India,” she writes, pointing to original myths where gods and goddesses were sexually fluid, and frequently even reversed gender roles; there are numerous accounts of androgyny in literature, drawing on examples from books by Madhavi Menon and Ruth Vanita, which also illuminate how gender boundaries and sexual codes were previously much less defined. In an instance uncited by the author, Vanita’s Memory of Light is about the romance between the female poet Nafis and the courtesan Chapla in 18th-century Lucknow. More importantly, Rajasekaran and these other authors highlight the extent of freedom, sexual and otherwise, that women once enjoyed. There is also Manu S Pillai’s The Courtesan, the Mahatma & the Italian Brahmin (2019), which showcases many examples of women with power and agency. Such agency alarmed the Victorian colonisers. They didn’t take long to deem such women ‘prostitutes’. This was applied to all women outside of Hindu monogamous marriages, including widows; thus all women who stepped outside of the role Victorian morality allowed them were tainted. Those who embraced their queerness and blurred sexual boundaries were termed ‘deviants’. The colonisers didn’t stop there, they indoctrinated Indian men and made them the agents of their purpose, leading them to repress Indian women.

Rajasekaran’s account shows the extent to which India’s patriarchy has its roots in its colonisers. Yet, she does not present an idealised view of pre-colonised India; she confronts its centuries of misogyny and caste-based exclusion. Forbidden Desire is painstakingly researched—evident in the number of sources and records referenced. But the book doesn’t read like a text. Her writing style is light, accessible and addresses the reader directly and informally. Interestingly, she spells ‘men’ and ‘women’ as ‘mxn’ and ‘womxn’ throughout the book to show ‘the diverse and fluid’ nature of gender, and the absence of boundaries. In her effort to reclaim this part of India’s history, she is also creating a revised language of her own. This can also be seen when she writes, “Queer folk need to write their own stories,…make their own spaces and code their own truths into performative art forms.”