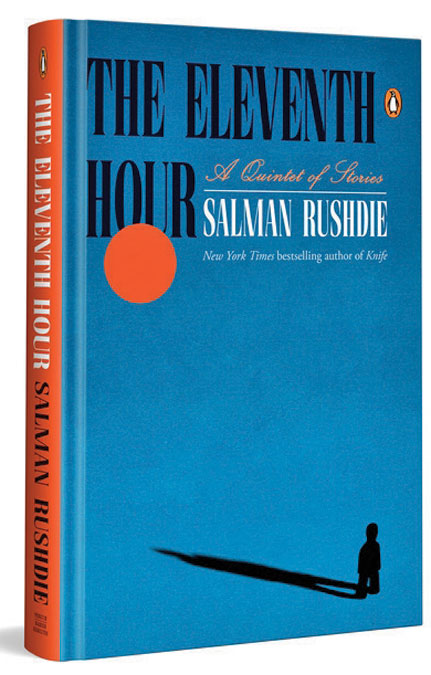

Salman Rushdie: The Vanishing Act

DEATH CEASES TO be a metaphor for those characters playing out the eleventh-hour plot variation in their lives. It is the meditative pause in the denouement, this sudden thrust of mortality in memory. In The Eleventh Hour, Salman Rushdie’s new collection of stories, they are a varied lot, unsettled by their own evening shadows. Among them: a man, suddenly deprived of his sparring partner, who realises that “death and life were just adjacent verandas”; the Honorary Fellow at Cambridge who wakes up dead; a writer obsessed with disappearances and guided by Kafka in his final journey; and a renowned old man, having lived through the ages of consensus and quarrels, succumbing to existential insignificance. Death, or the intimation of the end, doesn’t slacken the pace of Rushdie’s pages, the tone of which is indebted to his intimate conversation with mortality. The eleventh hour is a time for remembrance and redemption, and when it is Rushdie, fiction’s relentless fabulist, the shades of a life the enemies of storytelling dared to rewrite are an inevitable presence in the last stretch of the journey, the twilight of revelations.

The first story, ‘In the South’, featuring two old men and set in Chennai, merely named Senior and Junior, has the poignant note of a leave-taking and the weary banality of confinement. As Senior, on his loss on the sidewalk, on the sensation of the sparring coming to an end, says, “The old move through the world of the young like shades, unseen, of no concern. But the shadows see each other and know who they are. So it was with us. We knew, let me say this, who we were. And now I am a shadow without a shadow to shadow. He who knew me knows me nothing now and therefore I am not known. What else…is death?” In this story of sudden fall and slow descent, to bow out alone is to accept the quiet elegance of being alone in the void—and a leaner Rushdie makes the prose of valediction even more sombre.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Death is the belated answer in ‘Late’, staged in Rushdie’s alma mater, Cambridge, in which if the protagonist, the Honorary Fellow SM Arthur, rhymes with EM Forster, it could not be accidental. Rushdie adds to the enigma of his persona with a dash of the famed code-maker Alan Turing. Secrets, the best story in this collection says, are revealed in the faint glow of death: “In books it is necessary to bring things to a satisfying resolution. In real life things are not so neat. In my own case, the second secret will only be revealed when I am long gone. I fear it will soon be my time to die again.” Arthur lives in death for a final validation, and in real life, sexual orientation and betrayals take a higher price. The eloquence of a spectral life lets him set the record straight, and to read them as revenge or rancour is to minimise the magic of never closing the chapter—of keeping the possibilities of death alive.

‘Oklahoma’ is structurally ambitious as a meta-fictional foray into the art of disappearance, textual as well as physical. The manuscript left behind by the author Mamouli Ajeeb is a “narrative that is untrue and therefore true, as fiction is.” Kafka’s first novel, Amerika, provides the narrative propulsion to the relationship between the master and the protégé. In Amerika, Kafka abandons his protagonist, Karl Rossmann, just before he reaches his destination. In Rushdie’s story, the novelist of vanishings curates an elaborate performance of death, only to be exposed by the protégé—or an unrealised version of himself. Death, faked or “lived”, brings face to face the vanished and the abandoned. The dead and the living become one statement of fiction, the last truth.

Death, in ‘The Musician of Kahani’, a vintage Rushdie back in his original city which he now calls Kahani, is the music of retribution emanating from the frenzied fingers of a singer scorned. The story is populated by characters who bear an unmistakable Rushdie stamp. Meena Contractor is the no-nonsense matron of ambition and solidity, and her husband, Raheem Contractor, an academic drawn to a friend-turned-godman. Their daughter, Chandini, is a musical prodigy who gets married to a millionaire Parsi playboy, Majnoo. The newly minted godman calls himself Man in the Moon, shortened as Mithmu, who lures his old friend into his cult and makes him a soup maker. The apostle of sexual freedom and a collector of Ferraris, too, needs the consolation of disappearance in the final act. For Chandini, life in a gilded cage is confinement of art itself, and to break free she needs to send out the destroyer’s raga; and to be born again, death is a prerequisite.

Even arguments die, as in the last story, ‘The Old Man in the Piazza’. There was a time when—the Trumpian era?—arguments were an illicit indulgence, when there was only “yes” and its variations. Redemption comes when language itself rebels, and in this parable as protest, Rushdie asserts that language is the sole legitimate expression of conscience. When conformity prevails, language explodes, shattering the lies of the yes-world. ‘The Old Man in the Piazza’ is more an essay of dissent than a story with a message. It is a writer’s testament: language is freedom.

It is on that freedom, on Valentine’s Day in 1989, a dying revolution’s vengeful imam put a price. In exile, his books defied the dead certainties of the Book. More than three decades after the fatwa, in 2022, at a literary event in New York, the assassin caught up with him. Rushdie suffered multiple knife injuries, but, as confirmed by Knife, the memoirs of a fighter-survivor, and now by The Eleventh Hour, the storyteller has not lost his verve, the comedic flamboyance or the linguistic playfulness or the cerebral side glances. The story returns to its natural habitats—India, England and America—and at a slower pace, more reflection than razzmatazz, with the assured elegance of an evening sonata.