Burdened Riches

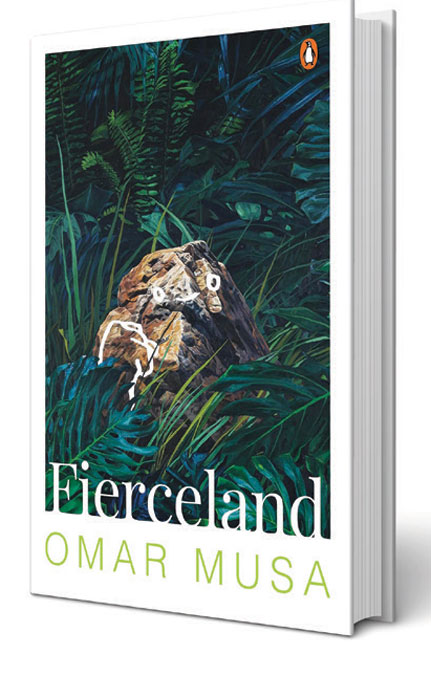

A LINE NEAR the end of Fierceland, by Malaysian-Australian writer Omar Musa, captures its essence: “Every rags-to-riches story is fertilised by blood, a great f*****g over of someone or something”.

This particular rags-to-riches story is about one of Malaysia’s richest men, Yusuf Mansur. This particular “f*****g over” is both large-scale and close-range. Mansur’s meteoric rise has involved denuding forests and snatching lands from indigenous communities, as well as leaving a trail of guilt, confusion and unease for his children.

Musa’s second novel opens with the children, Rozana and Harun, growing up in the 1990s in Sabah, northern Borneo. When Yusuf takes them on a work trip to a forest, they see him doing something terrible. After that, Roz retreats into art and schoolyard fights and Harun into prayers and piety.

Wealth flows in from his palm oil business and the children are sent to posh schools in Australia. Here the difficulties of assimilation singe as much as their past. They slowly drift apart.

Roz goes on to become an artist in Sydney, Harun turns into a Silicon Valley tech bro trying to recreate through virtual reality the kind of forests his father helped destroy. Things come to a head in 2018 when they return home for their father’s funeral and reckon with each other as well as their murky past.

Musa has Bornean heritage, though he was born and raised in Australia. Fierceland switches between first-person perspectives of Roz, Harun and other minor characters. It also toggles between poetry and prose, past and present, Borneo and Sydney, fabulism and realism. Musa is ambitious, unafraid to experiment with form and style in what at first glance is a standard novel about a family in crisis. In his fictional universe, a man can literally evaporate, a trinket takes centrestage as it travels from Italy to Malaysia and the forest is given a voice.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

At its heart, this is a novel about ecological disaster, about cultural erasure and filial guilt. What is the cost of getting to the top? What happens once you get there? And is it possible to make reparations? This is also the story of Malaysia, the suturing together of a nation, and the many large and small violences involved.

Fierceland works best when it focuses on the siblings, their relationships with their parents and with each other. The childhood chapters glisten with foreboding; the intrigue of knowing something bad happened, yet being unable to fully grasp it. Even Crazy Auntie, the family friend whose on-the-nose portraiture as the truth-telling mad woman evades caricature.

Musa wants to reclaim a people and a way of life through this novel; an entire section is dedicated to a single poem called “The Song of the Wood” which is painstakingly translated into multiple Sabahan languages, some nearly extinct.

Apart from this linguistic experiment, Fierceland frequently lapses into non- English words. To Musa’s credit, he does not patronise the reader by translating each time. But does that somehow make it more authentic? Does gesturing at cultural unknowables freight them with greater meaning? Som-Mai Nguyen captures this tendency in an essay called “Blunt-Force Ethnic Credibility”: “There’s a jazz-hands half-nelson device I dislike in diasporic literature and criticism. Writers extrapolate from orthographic coincidence and sprinkle in non-English words to assert unearned authority.”

Not just that. There is something essentialist about the way Borneo is portrayed: the kind forest people, the ancient and wise trees, the eternal river simply called River. Prominent novelists have heaped praise on the book—three blurbs describe the book as “urgent”. I suspect that’s coded praise for good politics as much as good craft. No doubt this critique of hubristic wealth-seeking, tech disruption and deforestation comes from a place of good intentions. But despite its fizzy energy and the lively family saga it often feels didactic.