When Shadows Speak

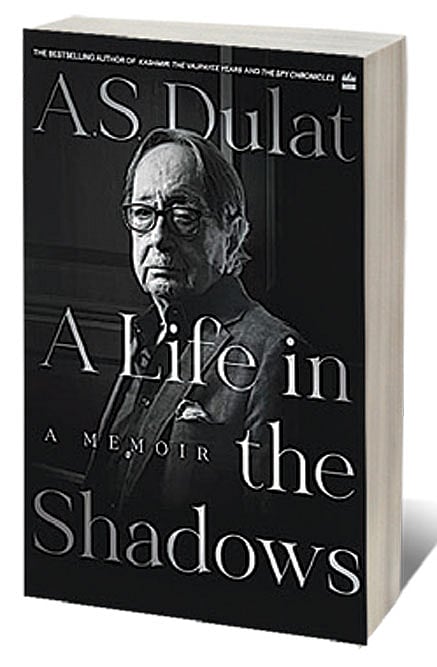

AFTER HIS TWO books, the unreservedly open account of his work in Kashmir in The Vajpayee Years (2016) and the more explosive account of his work in the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) with his Inter- Services Intelligence (ISI) counterpart in The Spy Chronicles (2020), AS Dulat is being excessively modest in calling his biography A Life in the Shadows. His life has hardly been in the shadows.

It is perhaps a structural lacuna of autobiographies that the author remains firmly in the centre of his own cosmos. One may wonder whether stepping back a few feet from the centrestage may have helped him to examine the core concerns of his age or chronicle his times better. Distance may have also helped him to talk less about his junior colleague—Ajit Doval. Whether he was persuaded by his publishers, with an eye on the saleability of his book, to write a separate chapter on Doval or he sincerely felt the need to pay such glowing tributes to the latter’s spy-craft is unclear. Be that as it may, a more important question is left unanswered—as to whether between the Dulat doctrine and the Doval doctrine, there is any hope for Kashmir. Anyone familiar with the trajectory of the Kashmir problem knows that while Dulat advocated “talks and engagement,” Doval preferred using the full coercive power of the state and a “muscular” policy of “tit-for-tat” for the terrorists fighting the Indian state. These are only two different approaches to a problem—the “good cop, bad cop” scenario. There is little doctrine to it.

Surely, to be called a doctrine, there have to be some elements that could go into making the framework of an agreement, what would its contours be, up to what point would the Indian state negotiate and what is non-negotiable, what are the demands of the Kashmiris that can be met within our Constitutional confines or within the framework of “Jamhooriyat, Kashmiriyat and Insaniyat,” a formulation that only Vajpayee could have come up with, which swayed the Kashmiris in an unprecedented way, probably because of both its fuzziness and poetry. Was either Dulat or Doval given a free hand to craft Vajpayee’s doctrine? And is the Doval doctrine different from Home Minister Amit Shah’s doctrine, which in turn is shaped by the ideology of the Sangh Parivar, namely to crush the militancy, subjugate the Kashmiris by breaking the state into two Union Territories, remove its special status and try to change the demography so that the Muslims are reduced to a minority and then hold elections in the state? Dulat says that this policy has further alienated the Kashmiris and has clearly failed. What then is the solution?

Braving the Bad New World

13 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 62

National interest guides Modi as he navigates the Middle East conflict and the oil crisis

The current narrative is that Kashmir has been historically held to ransom by three families—the Abdullahs, the Muftis and the Gandhi family, meaning the Congress party. If we were to dismantle the three families, what are we left with—Shabbir Shah and the Hurriyat Conference, which is now reduced to Mirwaiz Umar Farooq? Neither of them represents anything or anyone more than themselves and the Hurriyat has stubbornly refused to take part in the elections, thus keeping away from any legitimate process of joining the Indian state. So, Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh have failed to resolve the problem. Now is the turn of Narendra Modi, Amit Shah and Doval to try out their new method.

The fact that Pakistan is the big elephant in the room, which will not permit a resolution of the Kashmir issue without taking its pound of flesh has always complicated the matter. Both Dulat and Doval are acutely aware of it, and both have participated in dialogues with Pakistan either directly or through Track-II meetings. Now the present government has stopped talking to Pakistan too. Neither Pakistan nor Kashmir will disappear if we don’t talk to them. And we continue to grapple with the problem.