Vajpayee’s Balancing Act

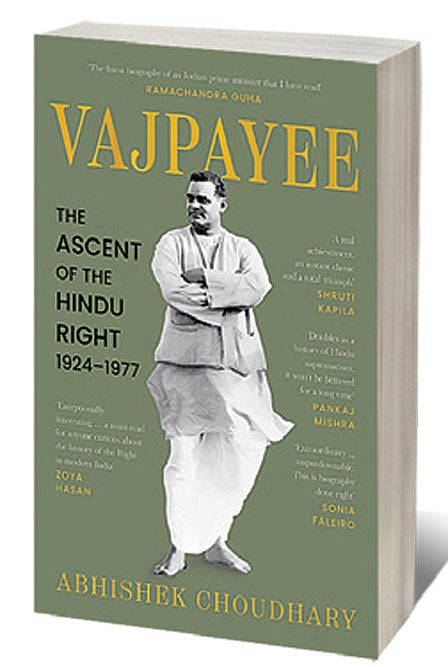

IN HIS PRAISE FOR Abhishek Choudhary’s biography of former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, RSS scholar Walter K Andersen notes, “Anyone seeking to understand why Hindu nationalism plays such a key role in current Indian politics needs to know Vajpayee’s role in making it a powerful force by a shrewd balancing of ideology and pragmatism”. Indeed, in his new book, Vajpayee: The Ascent of the Hindu Right 1924 to 1977, Choudhary traces Vajpayee’s trajectory of political growth from his early years in Bateshwar (near Agra), Gwalior, and Kanpur, and as an RSS activist until he was picked for the post of external affairs minister in the first non-Congress government in India in 1977. It also covers Vajpayee’s brief association with the most prominent Communist student union of the time and his ‘role’ in the Quit India movement.

To sketch an accurate picture of the man who would go down in history decades later as the first non- Congress prime minister to complete a full term in office, Choudhary painstakingly examines the young Vajpayee’s early writings, many of which reveal a hard-line Hindutva stance clouded by arbitrary inferences and popular misconceptions. In the pro-Hindutva magazine Rashtradharma, Vajpayee and his cohort wrote articles that lapped up the glory of ancient India or as, Choudhary says, “presented historical fiction based on Hindu scriptures”. The author does a lot of digging up to secure information from primary sources such as these write-ups.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

We all know that Vajpayee’s pragmatism hinged on the political mood of the time, which was dominated by Nehruvian modernism and dreams of socialism. And yet, he professed opinions that were hardcore Hindutva. He kept his party colleagues close as a deft political schemer within. And over time, he appeared to mellow down for political expediency—perhaps a ruse to keep his rivals closer as a moderate face from the Bharatiya Jana Sangh founded by his one-time mentor Syama Prasad Mukherjee in 1951. This balancing act was, in fact, political posturing, as Choudhary demystifies, drawing on numerous articles and speeches by Vajpayee from his formative years in politics to the time he became part of the 1977 government led by Morarji Desai.

The shrewd balancing that Andersen refers to is obvious in the following lines from a late 1940s essay of Vajpayee’s that Choudhary has ferreted out: “After Pakistan came into existence, Indian Muslims have changed colours like lizards. They keep pledging their loyalty to the Indian Union and have agreed to bow down before the tricolour flag. Some people are over-excited to see this sudden change in their mentality. In reality, this is no reason to be happy. The Muslims have only one motive, and that is to strengthen Pakistan. And to fulfil this overarching goal, they are desperate to do everything…. Thinking of Hindus as disunited, the League will do everything to weaken India’s strength, and in that struggle, the Indian Muslims will act as fifth columnists.”

The author also has done extensive reading of Vajpayee’s articles in Panchjanya, which was launched in January 1948. In a matter of days, the assassination of Gandhi changed everything, and most importantly put an end to the bloody riots and then threw the RSS, which Vajpayee was part of, in a bad spot. The author highlights a perpetual Vajpayee characteristic that he would display every time the organisation’s credibility slides: utmost loyalty. Years later, following the demolition of the Babri Masjid, too, he would do that, armed with the halo of being a moderate that he has acquired thanks to his pragmatism and cunning.

Choudhary, besides busting oft-repeated inaccuracies about Vajpayee’s life, explains how his tightrope balancing act made him a grand success and narrates with aplomb the story of this man of contradictions. This is a political history of the period under study.