Muscle Power

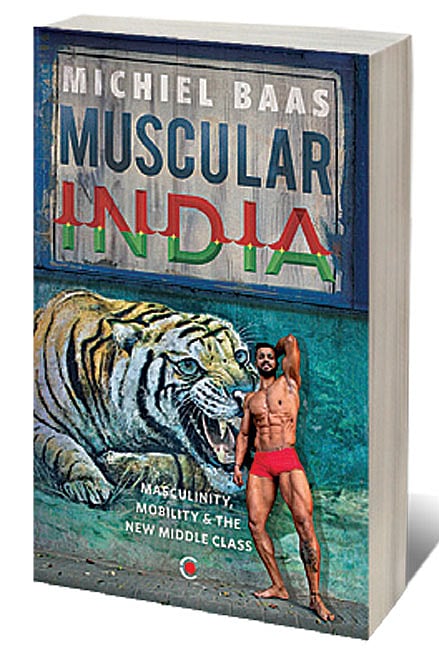

IN THE 1980s, the delightful ‘Sunday Ho Ya Monday Roz Khao Ande’ jingle by the National Egg Coordination Committee was one of the most popular ads on Indian television. An ad in this campaign featured a half-naked bodybuilder with a thick moustache flexing his muscles; seemingly built by consuming eggs. A lot has changed since these Pre economic liberalisation days. As per a Deloitte India report, the wellness and fitness industry’s worth in India crossed $1.1 billion in 2017. This growth, enabled by the ever-increasing disposable incomes of the middle class and rapid urbanisation has also created a great demand for fitness trainers. For crores of lower-middle-class men, the job of a fitness trainer has become a vehicle to achieve socio-economic mobility. But is the bodily capital—of having a muscular body and possessing the knowledge of how to build one— sufficient for these men to overcome the limitations of sociocultural capital (family, caste) and be accepted as middle class? Muscular India: Masculinity, Mobility and the New Middle Class, an exciting new book by anthropologist Michiel Baas, attempts to answer these questions and more through an ethnographic study of the lives of trainers and bodybuilders across India.

During his decade-long research, Baas met, became friends with and interviewed personal trainers with upper-middle-class clients, floor trainers in a neighborhood gym and bodybuilders across India’s metros. In a thrilling introduction, he dwells on how the popularity of the transformed bodies of the three Khans—Salman Khan in Pyar Kiya To Darna Kya (1998), Shah Rukh Khan in Om Shanti Om (2007) and Aamir Khan in Ghajini (2008)—and the launch of the Indian edition of the Men’s Health magazine (2007) gave birth to a new ideal of the Indian male body. Baas argues that the promise of transformation, set against the background of a rapidly transforming urban India, led to a ‘rapid growth in gym memberships and demand for personal training’ amongst the 30-crore strong middle-class India. Interviews with trainers reveal that although the trainer-client relationships inside the gym are that of equals, gaps remain in their outside lives. Add to this the reluctance of the older middle class to accept these new entrants and the negative associations attributed to muscular bodies in a society infamous for violence on women and the complexities of the Indian context are evident.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In the chapter on bodybuilding, Baas briefly traces the history of bodybuilding in India from the Eugen Sandow’s visit in 1904-1905 to the inefficient contemporary system marred by the proliferation of federations across the country. He writes evocatively about the struggles of bodybuilders to meet the financial needs of their families while keeping up with extreme workout routines and investing in protein supplements. Despite their harmful effects, the use of growth hormones and anabolic steroids seems to be rampant in the sport and the grim accounts of the bodybuilders almost make their consumption sound inevitable. Perhaps, the most intriguing and less-known subject is the chapter on sex and desire in which Baas writes on the sexual capital of a muscular male body and also its exploitation.

Baas intersperses narratives of his interactions with the trainers and body builders with scholarly analysis; this constant shifting of styles can be taxing for some readers. Passages where he describes the intimate time spent with these men, such as his journeys with Shivam, conversations with Manish and Selvam and the Ganapati Visarjan procession in Mumbai with Vijay are delightful and subtly let us into their complex world of aspirations, anxieties and insecurities. Apart from extensive field research, Baas analyses Bollywood and published works—both scholarly and otherwise—to develop his arguments thus resulting in copious notes and a very helpful bibliography.

Muscular India does a great job of breaking down (some of) the complexities of internal middle-class hierarchies and is a significant addition to the study of contemporary Indian middle class. Baas’ decision to publish his research for popular consumption is commendable and will hopefully encourage other eminent researchers and scholars to follow suit.