Indira’s India

THERE IS A veritable industry when it comes to biographies and studies of Indira Gandhi, her life and the India she ruled over. Every decade since she was elected as Prime Minister has seen the publication of a major biography. The quality is inversely proportional to the number. Some of them are plain outrageous attempts at exculpating her record as prime minister; others swing to the polar opposite direction, personally blaming her for all that went wrong between 1966 and 1984, the two decades in which she dominated India’s politics.

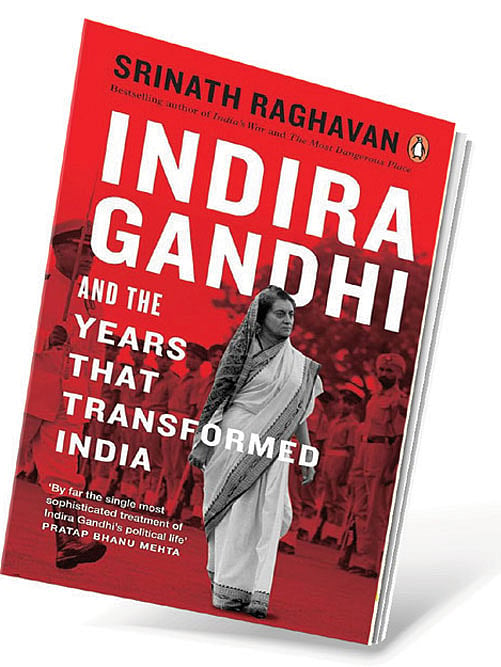

Why publish a book on her now, long after the tumultuous events of her time have almost faded away? Perhaps this is the best time for such an exercise, one where her tenure as Prime Minister is evaluated coolly by assigning proper weights to events, ideas and personalities. Srinath Raghavan’s Indira Gandhi And The Years That Transformed India does so capably. He excoriates her for her faults but also highlights the “structural” or “environmental” variables that made her age so difficult and volatile for India and Indians.

The explanation is believable. By the time Jawaharlal Nehru died in 1964, the old order that had prevailed since Independence had begun to crumble. At the same time, the “period of patience” that every de-colonised country gets, one where citizens wait for a better life, had nearly come to an end. This played a big role in the political and economic choices that Indira Gandhi made. They interacted in a complicated way and created several problems in the next two decades. It is interesting that Raghavan highlights the ideas in ‘The Report of the Committee on Distribution of Income and Levels of Living, Part I’ (Planning Commission 1964) and those in an earlier paper, ‘Perspective of Development: 1961-1976, Implications of Planning for a Minimum Level of Living’ (1962). Both documents highlighted problems that had been ignored by Nehru: poverty and income distribution. These were thought to be secondary to the key problem of the Indian economy, industrialisation and economic growth. In Indira’s tenure distribution acquired greater salience over increasing output.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

In Indira’s hands and those of her advisers like PN Haksar, these issues acquired an extreme leftist direction. This served Indira’s politics especially after 1967 when she began eliminating her political rivals in the Congress party. While these ideas delivered political dividends, they wrecked the Indian economy. It was only in the mid-1970s at a time of economic and political chaos due to socialist economics gone haywire that a course correction was attempted. This began after nationalisation of grain trade was rolled back in 1974. By then, the international oil crisis, the pervasive shortages in the Indian economy and the almost uncontrollable inflation had spilled over into the political domain. The Emergency came a year later.

It would, of course, be disingenuous to blame the Emergency on economic problems. These were, after all, deliberate choices that were made by Indira and her advisers. Raghavan does not take that route, but highlights the complex interplay between economic and political factors that made for a mess.

The novelty of Raghavan’s book is two fold. The conventional measure of approbation in such studies is how far a scholar has plumbed the archives to buttress new claims as well as close the gap between what was believed about a historical figure earlier and what new archival finds reveal. By this standard the book stands out.

But there is another, even more novel, feature of the book but one that Raghavan does not take to its conclusion. Instead of a bland narration of facts interspersed with interpretation he tries to explain those tumultuous decades using a very different theoretical approach, one not usually used to explain domestic politics. This is the “systems” approach of the International Relations (IR) scholar, the late Kenneth Waltz. The attempt in the book is to figure the political outcomes at the system-level by looking at the interplay between its parts, the executive, the judiciary and Parliament.

He writes, “The systemic change in Indian politics was not merely due to the rise of new actors, parties, and social groups in politics. The change took place, above all, at the level of system-wide components that influence all actors.” (Emphasis added). These were the institutional arrangements of political actors according to their differing functions and relative powers and, secondly, the rules, procedures, principles and norms that regulate the pursuit of goals by different political agents. Both came under exceptional strain during the two decades that Indira Gandhi dominated Indian politics (1966-1984). (See pages 22, 144 and 180, where he highlights the system-level disequilibrium in terms of these three “units”.)

There is, however, a great deal of difference between applying a Waltzian systems perspective at the global and domestic political levels. At the global level anarchic competition prevails because of “unit-level” competition between nation-states as there is no “global government”. It is tempting to think that the “anarchy” of the Indira years was due to a similar unit-level competition at the domestic level. But the analogy breaks down beyond a point. If some analysts are to be believed, the problem in those decades and later as well, lay with a particular unit: legislative majorities leading to a strong executive. This was considered a problem in 1971 as it is by some contemporary observers as well. To be fair, Raghavan’s book does not suffer from any of these “presentist” blemishes unlike two other recent studies of the period dealing with the Emergency.

Theoretical perspectives to explain historical events can be hazardous. But since IR theory has been pressed into service, might one suggest that a “constructivist” approach—one where reality acquires meaning through ideas and beliefs—will be much more interesting. Who can doubt that the late Prime Minister thought in those terms?

There is one, relatively minor, quibble in this thoughtful book. This is towards the end where the author tackles three difficult subjects: the problems in Assam, Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) and Punjab. This is a relatively thin gruel. Perhaps this has to do with the fact that these problems unfolded fully during the Rajiv Gandhi years. Or perhaps more mundane factors are at work: the length of the book would have gone up significantly in case a fuller treatment was carried out. It is interesting to note that while archival sources have been used extensively for understanding developments in J&K, there’s much heavier reliance on secondary sources in the case of Assam and Punjab.