Historical Lives

ONCE UPON A time History was simple. Indians of a certain vintage will remember school history as a collection of kings, dates and events. The subject was a confused mass of disparate ‘collections’ that contrasted with an ‘ordered’ discipline like physics with its neat formulae. For a young person trying to grasp something real, the lack of predictability added to the indecipherable nature of history.

In retrospect, the study of accidental events with no motive force—just the plain rise and fall of dynasties, empires and great men and women—appears comforting. Once someone has read Karl Marx, the idea of history having a purpose seems hard to dismiss. It takes a lot of time and no small amount of common sense to realise dangers that lurk in the idea of history with a purpose. It took a century of bloodshed, tyranny, war and oppression—all in the name of a better future—to appreciate ‘simple’ history. That realisation is now ingrained in how history is understood in Europe and the wider West. In India, it continues to be resisted tooth and nail by an obdurate establishment of historians that clings to ideological interpretations of the past. That was not always so.

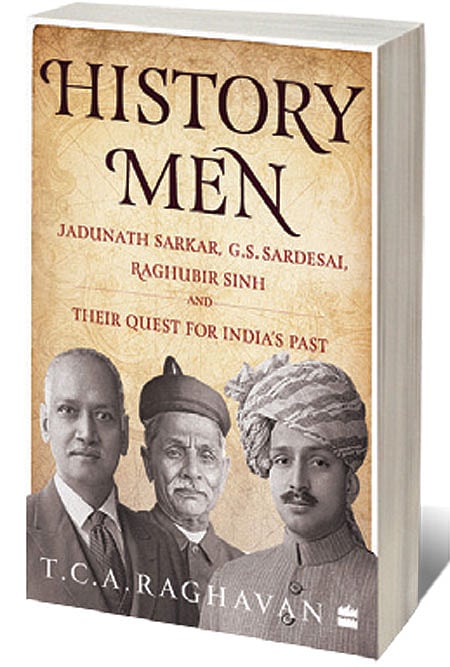

TCA Raghavan’s History Men is a different take. It is not a usual history of some period of India but a ‘history of historians’. The protagonists of the book were not only pioneering historians but were perhaps the last ones who went to great lengths to unearth facts and allowed facts to speak for themselves. In this they, wittingly or unwittingly, followed the paradigm of the great German historian Leopold von Ranke (1795-1886). GS Sardesai (1865-1959) and Jadunath Sarkar (1870-1958) came of age at a time when nationalist consciousness was developing in India. History writing and discovery of the country’s past was a nascent undertaking that was in the hands of Europeans. It was also hard work.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Between them, Sarkar and Sardesai hunted for written sources across the length and breadth of India. Unlike today, English translations of documents, proper archives and other historical tools were absent. Gathering, transcribing and translating records consumed a major portion of a historian’s time. To give one example, the papers at Poona Residency alone were in tens of thousands. There was an archives department but that was more or less a storehouse of sorts.

The output of the two scholars was prodigious by any measure. Sardesai’s Marathi Riyasat (in eight volumes), Sarkar’s History of Aurangzib (in five volumes) and The Fall of the Mughal Empire (in four volumes) were Gibbonesque ventures that are daunting achievements that will put contemporary historians to shame. These are the most wellknown works of the two authors: their total output was much greater.

Later on, they were joined by a third—much younger—historian: Raghubir Sinh (1908-1991), heir to the princely state of Sitamau in Central India. It was an unusual combination. The prince’s foray into history was a historical accident of sorts. His father, Raja Sir Ram Singh, was an astute person who kept an eye on the events of his day. Raghavan notes how after the Russian Revolution, the ruler of Sitamau realised that the future of his state and his children could be very different from the certitudes of his time. If that were not enough, the state’s somewhat uncomfortable position in a territory dominated by bigger states like Gwalior was always a source of unease. Sinh’s doctoral dissertation, written under the guidance of Sarkar, was later published as a book. Malwa in Transition or a Century of Anarchy: The First Phase 1698-1765 (1936) dwelt on theme. Sinh’s appreciation of his native land informed his submission before the States Reorganisation Commission (1953-1955). It was ignored as the priorities of the new Government were very different from the kind of concerns that Sinh had.

In the end, the Rankean renaissance in India enjoyed a very brief life. Five years after Sarkar’s death appeared the first serious work of interpretative history. Irfan Habib’s The Agrarian System of Mughal India: 1556-1707 (1963) cast a very different light on Mughal India from what Sarkar and Sardesai had written. Gone were factual histories that allowed readers to make up their mind and, if they were up to it, explore historical themes on their own. Henceforth, there would be specialist historians who would write and interpret the past not just keeping in mind their readers but also the sensitivities of the political climate in the country. Perhaps that is too harsh a judgement but it is proper to say that the ‘new’ histories sanitised the past, making it safe for the present. The crisis of credibility in Indian history dates to that period.

Worse was to follow for Sarkar. In 1990s, it was not uncommon for him to be called the ‘doyen of communal historians’. In reality, Sarkar was no such thing. Anyone who has bothered to read the History of Aurangzib (and not A Short History of Aurangzib) can only have a degree of appreciation for Aurangzeb as an administrator and as a prince who remained out of favour in the court of Shah Jahan. It is only in the third volume of the History that Sarkar elaborated on themes that were to become contentious in the later part of the 20th century. Aurangzeb’s religious bent, his bigotry and the overreach of the Mughal state under him are all matters of fact. They deserved a proper interpretation. Instead, there were two ‘interpretative equilibria’ so to speak: an interpretative denial, most clearly seen in the works of some historians from Aligarh or blaming ‘Hindu fanaticism’ for giving the last of the Great Mughals a bad name. Audrey Truschke’s Aurangzeb: The Life and Legacy of India’s Most Controversial King (2017) is an example of the latter trend.

Raghavan’s Sarkar is a very different historian. While reading Sarkar’s work, Raghavan has been careful and fair to him. In this, he follows a recent and far fairer re-appraisal of Sarkar, one that began with the publication of Dipesh Chakrabarty’s The Calling of History: Sir Jadunath Sarkar & His Empire of Truth (2015). There is always room for overturning of historical facts and interpretations in light of new material. But interpretations based on ‘sensibilities of time’ are as pernicious as the politics that informs them. It is heartening to note that Raghavan has taken great care to show what the aims of India’s pioneering historians were all about. The three historians, two professionals and one prince, were far-removed from the history wars of the late 20th century and were scholars with a zeal that is unknown today.

There are very good reasons to be pessimistic about knowledge of India’s past. History writing is now a highly contested domain that has percolated to genetic studies of Indian populations. But in books like the one Raghavan has written, there is hope for a balanced appraisal. Hopefully, someday, India will get the history it deserves, one that is not good or bad history but just plain history.