Modi’s Masculine Nationalism Faces up to Pakistan

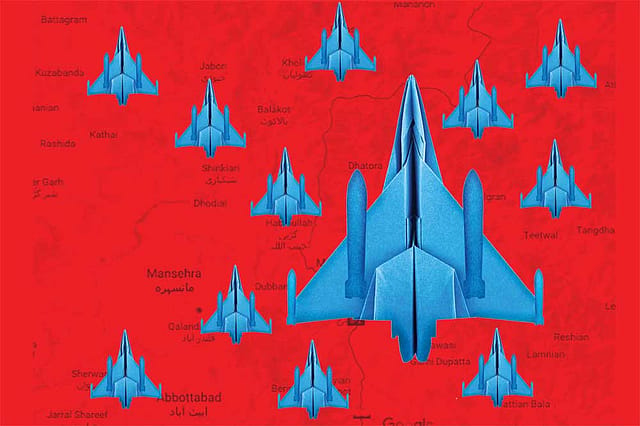

ON FEBRUARY 27TH, WHEN PAKISTAN used US-made, agile, new F-16 aircraft to unsuccessfully bomb Indian military facilities in Kashmir, American President Donald Trump was away in Hotel Metropole in Hanoi, Vietnam, to hold parleys with the recalcitrant North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, offering to make the East Asian country an "economic powerhouse" if it became friends with Washington. The irony was inescapable: it was his Republican predecessor George W Bush who, in the face of stiff opposition within, decided to sell new F-16s to Pakistan as an incentive for cooperating with the US on its 'war on terror' in response to the 9/11 attacks, just as his own predecessors—especially Ronald Reagan—who promised to make India's dodgy neighbour an economic and military power had sold it an earlier version of F-16s in the 1980s. Christine Fair, author, academic and expert on Pakistan's military and non-state actors, thundered on an Indian TV channel,

"Shame on you, George W Bush", referring to his nod to that sale of new F-16s.

America, meanwhile, came under tremendous diplomatic pressure globally to put its roguish south-eastern ally on a leash even as Trump faced trouble at home as his former fixer and lawyer Michael Cohen prepared himself to plead guilty in a Congressional testimony of complicity in frauds at the behest of the US president in breaking campaign finance laws. Cohen also called Trump a conman and a racist. Trump denied any wrongdoing.

DANGEROUS LIAISONS

Pakistan's use of stealthy F-16s—which Americans claim they do not sell to untrustworthy nations—to target India was in response to New Delhi's February 26th offensive deep into Pakistan where 12 Mirage 2000 fighter jets pounded what India said were camps run by terrorist outfit Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), which, headed by terrorist Maulana Masood Azhar, had taken responsibility for the suicide attack that killed 40 Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnel at Pulwama in Kashmir on February 14th.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

Edward Luttwak, cold warrior, military historian and strategist, has always shared the anger that many Indians had of their leaders not doing enough to stop Pakistan from waging a proxy war on their soil through non-state actors such as Lashkar-e-Tayyaba (LeT) and JeM. He has often poked fun at India for not modernising its outdated weaponry and has described the use of MiG-21 Bisons of 1960s vintage as "putting lipstick on an old hag".

He is of the view that India's failure to retaliate in the past—after the Mumbai terror strikes of 2008, popularly called 26/11, which were carried out by Hafiz Saeed-led LeT— had created a lot of "confusion", which, he insists, is now over thanks to the clarity offered by the "measured retaliation" of the early morning of February 26th. It was for the first time in 48 years that Indian fighter planes crossed over to Pakistani territory to bomb JeM targets in multiple locations, including Balakot, which falls in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (KPP) of that country. Indian Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale said in a press briefing in Delhi that the fighter jets that launched the pre-dawn attack eliminated a "large" number of JeM cadres, trainers and senior leaders.

A day later, Pakistan, which claimed there were no casualties in the Indian attack, launched strikes on India only to be repulsed immediately, according to Foreign Ministry spokesperson Raveesh Kumar. While the Indian Air Force (IAF) shot down a Pakistan Air Force (PAF) aircraft, Kumar said, India lost one MiG 21 in air combat. "The pilot is missing in action. Pakistan has claimed that he is in their custody. We are ascertaining the facts," he disclosed in the afternoon of February 27th, hours after video clips of the pilot, Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman, were circulated online by Pakistan in gross violation of the Geneva Convention, an international code brought in after World War II to restrict the barbarities of war.

Most military experts and diplomats that Open spoke to on the day India launched aerial strikes across the border were of the view that Islamabad would not retaliate through conventional ways, suggesting that it would, at the most, resort to punitive diplomatic options. Even someone as incisive as Christine Fair had downplayed a Pakistani retaliation to India's avenging of the Pulwama terror strike.

US analyst and the Wilson Center's Director of Asia Program Michael Kugelman said Pakistan would perhaps recall its high commissioner from Delhi. It was most likely, he said, that Pakistan would stick to its tried-and-true tactic of having non-state actors stage attacks in India. "The latter tactic, in fact, could be intensified," he noted.

However, Indian Defence Ministry officials said they had anticipated a counter-attack, considering the pressure from opposition groups within Pakistan that had goaded the Imran Khan-led dispensation to retaliate.

STRANGE OBSESSIONS

Pakistan has always wanted to live by what it considers its destructive military goal to 'bleed India by a thousand cuts'. Islamabad had been at it for long. Which is why at least three armed forces officials that Open spoke to on February 28th contend that, so far, the actions of poll-bound India and an India-weary Pakistan were along expected lines. "Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan was under intense political pressure. You have to bear in mind that it is a country where the army calls the shots and where non-state actors are considered prized assets, cheaper and perhaps more effective than the officers," says a senior army officer. JeM, in fact, is crucial to what Luttwak, author of Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, calls "Pakistan's grand strategy to hide behind jihadists". Fair writes in her recent book, In Their Own Words: Understanding Lashkar-e-Tayyaba, that the deep state—players who manipulate the policies of the government— in Pakistan 'has continued to invest' in JeM because 'revitalizing JeM was a cornerstone of Pakistan's strategy of managing its own internal security challenges as well as a cornerstone of its policy of terrorism backed by nuclear blackmail to achieve its ideological objectives in Kashmir'. She writes in the book that 'in 2015, individuals from internal organizations tasked with monitoring these groups told me that since 2014, JeM activists have long been posed for infiltration into India along the line of control in Kashmir'.

Nuclear blackmail has always been the clincher for Pakistan, until February 26th when an impatient India struck back with force. That explains why on Pakistan's TV channels— such as Dawn News, Samaa TV and Geo News which were surveyed by Open—there was a sense of disbelief as the day began. The immediate reaction on TV channels that had experts and politicians on panel discussions was of shock. And then, slowly, wounded pride—a recurring theme in Pakistan since the humiliation it suffered at the hands of India in the 1971 war—set in. Since then, the Pakistan government and the military has used non-state actors and religious schools run by them to meticulously drill into the minds of young students a totally distorted picture of India as a satanic, anti-Islam entity that is home to kaafirs (unbelievers). On February 26th, Pakistani parliament—called the National Assembly—was chaotic, with leaders of all political persuasions appealing to Imran Khan to give India a befitting reply. Tweets by various politicians were as aggressive as their posturing in public. Bilawal Bhutto, Pakistan People's Party leader and son of the late Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, tweeted, 'India has chosen to respond to a homegrown, organic freedom fighters attack in Indian occupied Kashmir by conducting an airstrike on Pakistan soil for the first time since 1971. This outrageous and unprecedented act of aggression should be condemned internationally. Pakistan is well within our right to retaliate'.

For his part, Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) President Shehbaz Sharif—who happens to be former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif's brother—said that if India tried to launch a war, Pakistan would hoist its flag in New Delhi. Syed Fakhar Imam, a senior leader of the ruling Pakistan Tehreek- e-Insaf (PTI) called for a joint session of parliament to discuss how to respond to the Balakot attack. He said that the country had remained silent when the US discredited Pakistan by grabbing and killing Osama bin Laden at his mansion in Abbottabad, a Pakistani township that houses retired military officers. Imam argued that while Pakistan was bogged down by various compulsions back then, this time around, Islamabad must respond sharply to the violation of the country's air space by another country.

BREAKING NEW GROUND

On closer scrutiny, the Indian response to Pulwama and the Pakistani reaction have another aspect to them; one that was lost in the din for 'de-escalation' after Wing Commander Varthaman was captured in Pakistan-occupied-Kashmir (PoK). The issue can be framed in simple terms: how does a country that has to live under a nuclear shadow of a neighbour respond to terrorist attacks by that very neighbour?

India has faced this dilemma for almost a quarter century now. In the years after the Pokhran nuclear tests of 1998, it was felt that wars between India and Pakistan would become history as both countries would desist from attacking each other. But within months, the Kargil conflict broke out. That was the first time the two countries went to war after having acquired nuclear weapons. They had done so thrice in the past—in 1948, 1965 and 1971. Both took away very different lessons from the Kargil encounter. For Pakistan, it was clear that India could be stopped against considering any legitimate response to terrorist attacks. India erred on the side of caution and in return had to face a number of Pakistani terrorist atrocities that included an attack on Parliament in 2001, the 2008 mayhem in Mumbai, the killing of 18 soldiers in Uri in 2016, and the suicide bombing by a Kashmiri youth who was a member of the JeM on February 14th. It was this last attack that finally forced India's hand.

If all this was about terrorism on the ground, it was also about ideas. In the two decades since the 1998 tests, Pakistan has steadily redefined its nuclear 'redlines'. At one point, in 2002, the Pakistani general in charge of its nuclear weapons programme, Khalid Kidwai, clearly spelt out the circumstances under which his country would use these weapons against India. These included: India conquering a large part of Pakistani territory; destruction of a large part of its army or air force; economic strangling of Pakistan and pushing Pakistan into political destabilisation or its internal subversion. These clear redlines were quickly disowned when it was said that the decision to use nuclear weapons lay with political authorities there, and the latter would define the conditions under which they could be used.

Since then, these redlines have been consistently downgraded to the point that even the possibility of a least intrusive anti-terrorist operation against Pakistan is considered a 'nuclear flashpoint'.

In this pushing down of the nuclear rubicon, the Pakistani position has acquired a near-unanimous scholarly approval. On the one hand, India's weak military capabilities and the nuclear danger have been repeatedly cited as a reason for Indian inability to do anything against the terrorist menace. On the other hand, this was held as a normative ideal for India to follow. What was lost in this consensus was the threshold at which this would become too expensive for India.

That threshold was first tested in the aftermath of the Uri attack. At that time, it was held that the Narendra Modi Government 'used' the opportunity to buttress its national security credentials. The shallow Indian ingress across the Line of Control (LoC) into PoK was the first demonstration that even under a nuclear overhang, there was an upper limit to what India would tolerate.

Barely two years later, a similar situation emerged in the wake of the Pulwama attack. This time India enlarged the envelope and carried out a military operation in Pakistani territory across the International Border and not merely the LoC. This distinction is held important by scholars of nuclear theory, the claim being that any action across the LoC and the International Border will elicit different Pakistani responses. To an extent, events have proved this to be correct: In Uri, Pakistan denied that any military operation had ever taken place, except a bout of intense artillery fire across the LoC.

POLES APART

This time around, the contrast between the positions of India and Pakistan was glaring. India was careful—as clearly spelled out in Foreign Secretary Gokhale's statement—that India was hitting "non-military" targets from where the country faced the danger of further terrorist attacks, and hence the "pre-emptive" nature of these strikes. In contrast, Pakistan said that it had the right to respond to Indian "aggression". But it chose to hit Indian military targets in Jammu and Kashmir. The nature of this response has been the subject of a scholarly debate. Asfandyar Mir, a Stanford University specialist on Pakistan's military affairs, looked at the situation immediately after the Balakot operation in terms of credibility costs it imposed on Pakistan's military and political leaders and the strategic damage: if India thinks it can get away with action in Pakistani territory, it will be emboldened to strike again.

He made a clear distinction between the two: in case of the 'audience costs'—damage to the credibility of Pakistan's leaders—a slightly weaker response could be expected while the reaction strategic damage would be more severe. Where the scholarly narrative went off ramp was in assuming that India would not react to the atrocity in Pulwama.

It remains to be seen whether India can break out of the jam imposed by a nuclear overhang. Rajesh Rajagopalan, a professor of international relations at Jawaharlal Nehru University, looked at the costs of escalation and de-escalation after Varthaman was captured. In his analysis, this is a dangerous moment for India. If India escalates without adequate military preparation, it courts disaster. But if India de-escalates, it risks getting into a long-term strategic stasis that will impose equally severe costs: terrorist attacks will continue unabated. But much more dangerous for India will be the undoing of its efforts in the Balakot operation, leaving it in a far worse position. These are not ordinary calculations that can be made in a detached manner, but are high-level decisions for India's political executive.

As Open goes to press, the situation remains fluid. After Pakistan's attacks early on February 27th, there has been no major military escalation. Reports of heavy firing across the LoC continue to pour in. But this is a situation that has remained more or less constant over the last two decades barring a temporary interlude after 2002.

The other aspect of the situation is the diplomatic support India has received after the operation in Balakot, a place considered holy by jihadists. In her work, Partisans of Allah: Jihad in South Asia, Harvard University historian Ayesha Jalal talks of the warriors who fought a Sikh army: 'Accolades showered on the martyrs of Balakot and reverential accounts of the movement written by [holy man] Sayyid Ahmed's followers and admirers have since 1831 assumed such proportions that separating the myth from history is a difficult enterprise'. Now, one of the early supporters for India was France that promised to help India's case on terrorism at the United Nations. Soon after that, support poured in from other countries as well. Just after the Pulwama suicide bombing John Bolton, the US National Security Adviser, phoned his Indian counterpart Ajit Doval and supported "India's right to self-defence against cross-border terrorism". In the wake of the Balakot operation, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo issued a statement saying, "I also spoke to Pakistani Foreign Minister [Shah Mehmood] Qureshi to underscore the priority of de-escalating current tensions by avoiding military action, and the urgency of Pakistan taking meaningful action against terrorist groups operating on its soil." He also said, "I spoke with Indian Minister of External Affairs (Sushma) Swaraj to emphasise our close security partnership and the shared goal of maintaining peace and security in the region."

The Russian and Chinese reactions were muted and calibrated to maintain equal distance between India and Pakistan. In the case of Russia, the statement did not even mention Pakistan while the Chinese reaction was about the necessity of de- escalation and terrorism being a global problem, an anodyne formulation whose political emphasis was not lost on India.

As regards the US, Kugelman says, "Privately, you can be sure Washington is working the phones with interlocutors in both Delhi and Islamabad. While the US likely was supportive of India's strike, it won't want India to do anything else." He adds that Washington can ill-afford a war on the subcontinent while it desperately tries to hammer out a deal with the Taliban that enables it to leave Afghanistan. "The US has a tough balancing act: It will want to express its support to India as Delhi seeks to eliminate terrorist threats, but it won't want to alienate Pakistan at the very moment when it needs Islamabad's assistance in helping launch formal peace talks with the Taliban," he avers. Meanwhile, a diplomatic effort has been mounted to designate Masood Azhar of JeM a global terrorist. Azhar was released by the then NDA Government of AB Vajpayee along with two others from an Indian jail after a week-long crisis in December 1999 in exchange for passengers of Indian Airlines Airbus IC-814, which was hijacked by Pakistan-based terrorists.

POLITICAL OVERTONES

Amid chest-thumping and sabre-rattling on both sides of the border in TV studios, on social media and in public, India's ruling BJP came under sharp attack from the Opposition for using military action to gain a political edge. Though it was clear that the BJP, which is seeking a re-election after a five- year term that expires in a few months, will use the war-like situation in its poll campaigns, certain statements of senior leaders have invited criticism. Though the irony of an NDA Government freeing Azhar cannot be whitewashed, the Modi Government has won accolades for breaking the habit and acting decisively to warn Pakistan that its use of non-state actors would not be tolerated from now on. Yet, remarks made by the likes of former Karnataka Chief Minister BS Yeddyurappa that India's air strikes have created a wave in favour of Modi and will help the BJP win over 22 of 28 seats in his state in the General Election due by May, are being frowned upon. Similarly, in Ghazipur in eastern Uttar Pradesh, BJP President Amit Shah raised a question for the crowds on February 27th, hours after Pakistan targeted Indian installations for a foiled attack, asking if it is leaders of the gathbandhan or Modiji who can assure security. His assertion attracted criticism for being insensitive to the plight of the pilot under Pakistan's custody—Imran Khan announced only in the evening of February 28th that he would free Varthaman as a peace gesture to de-escalate hostilities. The 21-member Opposition that met on February 28th had lashed out at Prime Minister Modi for busily campaigning while the nation was faced with a security crisis. Modi was earlier criticised for taking part in a shoot for a TV channel on February 14th in a national park when the Pulwama attack took place. The ruling coalition dismissed the Opposition charge as frivolous. On February 28th, even as the situation remained tense and the IAF pilot's future was still uncertain, Modi addressed BJP booth-workers in a calibrated, interactive, televised event—where he pledged the nation won't bow down—attracting some flak for what his critics called his 'skewed priorities' at such a time. Meanwhile, writing in The Independent, author and journalist Robert Fisk warns India against allowing its military ties with Israel, its biggest arms supplier, to influence the country's political interests. He claims it was not by chance that the Indian press trumpeted the fact that Israeli-made Rafael Spice-2000 'smart bombs' were used by IAF in its strike against alleged JeM camps. He points out, quoting analysts, that right-wing Zionism and right-wing nationalism under Modi should not become the foundation stone of the relationship between the two countries. That is a disastrous proposition for a democracy like India, he argues.

Clearly, jingoism seems to have gained in fervour in a section of the television media, if not in the Government, which, many pundits believe deserves praise for being unprecedentedly stern on terrorism. A tweet by former Foreign Secretary Nirupama Rao critiques the apparent 24×7 war-mongering thus: 'The western front is not a TV studio anchored by those who are unqualified to dictate strategy and are unconscionable flame throwers. Our political leaders should not take the nation's temperature-readings from the seizure-like screaming on some media'. Winning a war is not all about making loud noises and trending hashtags on social media. In a modern war, very often, less is more. After all, in his Art of War, Sun Tzu says that 'the supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting'. This makes immense sense at a time in history when war is not merely a military assault but also a diplomatic offensive. Perhaps it is time to learn to unlearn.

Also Read