Black Noise

JUST 117 SPARSELY printed pages, the book has the lightness of a muted sigh, or an aside in isolation. Every sentence is like a stirring in a still world, shrunken to the size of a middle-class drawing room in New York City. The talkers are trapped, between anticipation and denial, between realisation and surprise. They talk shop with the mock seriousness of playful philosophers, with some Einstein thrown in. We read it in our own confinement, our own entrapment, in a pandemic world, and our consolation nowadays comes from Netflix rather than Nietzsche.

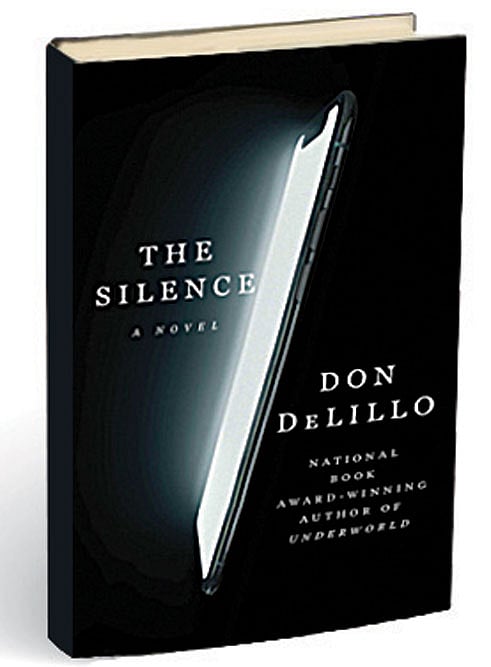

Don DeLillo, the last of the greats in American fiction (along with Paul Auster), has been here before, but not with this kind of austere premonition of apocalypse. This is as if he has chiselled an entire world of excesses to a miniature dystopia suspended in time. The Silence (Scribner, 128 pages, $22), DeLillo’s new novel, begins mid-air, in a flight cabin. Jim and his wife Tessa are flying back to New York from Paris. Their conversation is made of air-travel patois, of speed and altitudes and temperature. They are looking forward to watching Super Bowl LVI—the year is 2022—in the flat of their friends later in the day. Then: “A massive knocking somewhere below them. The screen went blank. Pilot speaking French, no English follow-up. Jim gripped the arms of his seat and then checked Tessa’s seatbelt and retightened his. He imagined that every passenger was looking straight ahead into the six o’clock news, at home, on Channel 4, waiting for word of their crashed airliner.” She says: “Are we afraid?” He doesn’t answer, instead thinks of “tea and sweets, tea and sweets.”

Elsewhere, in an Upper East Side flat in New York City, a couple, Max and Diane, and their guest, Martin, are waiting in front of a superscreen TV for the kick-off to begin. “Something happened then. The image onscreen began to shake. It was not ordinary visual distortion, it had depth, it formed abstract patterns that dissolved into a rhythmic pulse, a series of elementary units that seemed to thrust forward and then recede. Rectangles, triangles, squares.” What follows is total blackout. A digital suspension of life. In the stillness, in the electronic silence of dead algorithms, the only noise is the conversation of the three. The young Martin, a former student of Diane, is expected to speak smart. So he quotes from his most quotable source, Einstein’s 1912 Manuscript on the Special Theory of Relativity. Diane talks of him and their abruptly stalled situation: “In class you quoted footnotes. You vanished into footnotes. Einstein, Heisenberg, Godel. Relativity, uncertainty, incompleteness. I am foolishly trying to imagine all the rooms in all the cities where the game is being broadcast. All the people watching intently or sitting as we are, puzzled, abandoned by science, technology, common sense.” Soon Jim and Tessa, who survived the crash-landing, will join them, and they all become footnotes in a text of existential silence.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

The book could have been called, to improvise one of DeLillo’s previous titles, Black Noise. The noise comes from an abruptness, and it pervades the pages as disoriented and disconnected soliloquies from people punished by technological progress. They don’t know why they are trapped; they still don’t know what’s happening out there, whether it’s cyber-terrorism or foreign intrusion or some nameless digital voodoo or China. They create a fragile verbal alternative which holds them together, keeps them alive, for the moment, in this space of “dark energy” and “phantom waves.” Martin keeps returning to Einstein, who also provides the novel’s epigraph: “I do not know with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.” Martin carries within his head what Einstein sees beyond the current predicament. Are Martin and the four others in the room representative prototypes of a post-technological noir? Is it the pause before the end, the inevitable digital deep freeze? Is it that the Einsteinian “dependence of mass on energy” is having its moment of irony? Martin dreams of walking with the scientist “across the Princeton campus. Saying nothing, silent.”

Science doesn’t dazzle DeLillo. Science sets him on a journey to the future of imagination itself. In his last novel, Zero K, cryogenics is used to suspend death and enter immortality in the backdrop of a world on fire (‘Cryo-Nirvana with Don DeLillo’, Open, June 20th, 2016). The Silence was written before the pandemic. We read it in the middle of a pandemic, and when Martin reminds us that “nobody wants to call it World War III but this is what it is,” we realise that in our unsolicited isolation we are as abandoned as he and his companions in that one-bedroom flat in New York are. This is Don DeLillo, like Albert Einstein, as consolation and prophecy.