Shoaib Akhtar, Passing Through

The world according to a muscular man

The misfortune of Shoaib Akhtar is that for a man who loves lofty praise he will always be remembered as a Pakistani train. For some reason, no one has been able to think of a better compliment than 'Rawalpindi Express' to describe the fastest bowler ever clocked. Which makes Shoaib Akhtar the only sportsman in the world who is faster than his own metaphor.

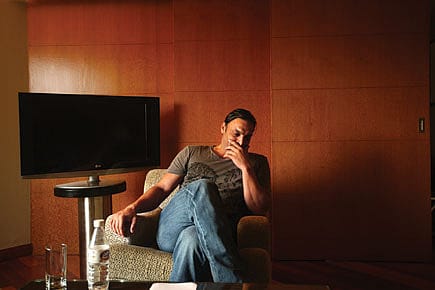

He is at the Hyatt in Delhi to promote his autobiography, oddly titled Controversially Yours. The girl at the door of his suite is Sudesh Rajput, his girlfriend for three years—a pleasant Delhi girl of austere beauty, who is reluctant to talk about her association with him. But she is very clearly his love, handler and some kind of filter.

Akhtar emerges from the bedroom looking like a Komodo Dragon. He has a grey stubble, his large baffled eyes look tired. As with most controversial people who know they are controversial, he has the bearing of a martyr.

There is something about muscular men that makes people, including other muscular men, first regard them as dim. But Akhtar quickly establishes that he has substantial son-of-the-soil wisdom. If you were to place him in your school classroom, he would be that philosophical thug. Despite everything, it is hard to dislike him after a point. Akhtar believes in the ability of all human beings "to see through" a man for what he is. And he has a good feeling about what they would see inside him. "If Indians come to know me, if I am allowed to interact with them, they will think I am not so bad."

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

He turns to Rajput, who is in one corner of the room, and says, "Coffee." He pretends that he is about to rise and help her, as if to suggest that he did not mean it as an order though it may have come across that way to the visitors. She saves the moment by offering to make coffee for everyone in the room.

He gathers his thoughts, looking a bit distracted at the same time, and says he is amused by the fact that the Bombay leg of his book promotion had to be cancelled following threats from Indians who claimed to be infuriated by his claim that Sachin Tendulkar was scared of him. What Akhtar is preoccupied with is the idea of fear. He likes the idea of fear. He likes to believe that fully grown men are terrified of him and that he himself is not scared of anything or anyone. He says that despite the fury of the Indian public he is not afraid of being in India, and he is not scared of saying what he wants to say. As proof, he says, "Shah Rukh Khan is an idiot" for criticising him without reading the book. A few days ago when a waiter at the Hyatt hotel asked him what he wanted to eat, he said, "bring me Kapil Dev". That is part of his imagined fearlessness—to sit in India and make jokes about Indian stars. "I have the phone number of a good hair transplant doctor for Sehwag," he says.

He is not very fond of Virender Sehwag, which is unfortunate because they talk alike. He and Sehwag have had one famous chat, which millions of cricket fans could not hear. It was on the pitch of the Centurion Park during the World Cup in 2003. Akhtar had been appealing constantly and at one point Sehwag said something to him. I was in the press box that day and the word was that Sehwag had said, "Are you appealing or begging?"

Akhtar says, "Sehwag spread a lie about what he had told me. He is not as gutsy as he pretends. He would not stand in front of me on a cricket pitch and say something like that to me." I imagine he is referring to the 'Are you appealing or begging?' statement. But according to Akhtar, what Sehwag had claimed to have done was point to Sachin Tendulkar at the other end and say, "Tera baap khada hai" (That's your dad standing there).

It is exactly the sort of thing Sehwag would say, but Akhtar fiercely denies that. "I know who my father is and if Sehwag had actually said that, I would have gone to his hotel room and hit him."

He lights up a cigarette and asks Rajput to keep the door open "please" to let the smoke escape. He has been smoking for several years. "Four or five a day." Does Sachin Tendulkar smoke? His eyes light up. He tries to look mysterious. "Never know what gods do," he says. He looks as if he wishes Tendulkar smokes. He hopes, for some reason, Tendulkar is flawed, that he is not as perfect as Indians would like to believe.

In his book he has shown some great players he dislikes in poor light and has drawn flattering portraits of some mediocre players who are his friends. This makes his autobiography a flawed story, like many autobiographies. But his desire to embarrass his foes also gives one a rare insight into the Pakistani dressing room. Pakistani cricketers have dismissed his opinions and interpretations, and have condemned his decision to reveal some secrets, but he maintains that nobody can question his facts.

Cricket fans have always known that Pakistan's dressing room is a snake pit, but some of Akhtar's accounts are baffling. It appears that one of the greatest sporting mysteries is how, for years, eleven Pakistani men on a high-protein diet somehow did not kill each other despite easy access to willow wood bats and sharp objects.

In his book, Akhtar describes the Pakistani dressing room as 'a place where wild animals are packed together'. He writes, 'Over the years, I have seen fistfights, knives flashed around, bats swung at each other—it never got out because everyone was doing it.'

There is a question the Indian government has asked Pakistan explicitly, and the American government has been hinting at in public statements: 'Who exactly is in charge of Pakistan?' As Akhtar brings together many strands of Pakistan's society to tell his story, it would appear that it is a question that can be asked in many rooms in Pakistan, including the Pakistani dressing room. It is a question whose answer keeps changing depending on who you ask and when.

There are portions in the book that carry the spirit and insanity of the great satirical novel by Mohammed Hanif, A Case of Exploding Mangoes. These portions tell the story of a fellowship of men who are comically religious, paranoid, scheming and not always in control of themselves. It is not Indians but Pakistanis who should be upset with Akhtar for embarrassing them in a book that does not even have the masquerade of 'fiction'.

Akhtar grew up in poverty in Rawalpindi as the son of a watchman. Cricket saved him. He has in him the pride of a person who has made it on his own steam, but he has an unambiguous adoration for men of class. He says Pakistan and its cricket must be led by "men who have been to Oxford".

"Like Imran Khan," he says. "He has class, articulation, vision."

When Akhtar later reveals his world view, his analysis of terrorism and his opinion of the United States, he repeats almost exactly what Imran Khan recently said in an interview.

"But what a strange country Pakistan is," Akhtar says, somewhat ponderously, "Imran Khan was beaten up by some people in public. That can never happen in India to an Indian cricket legend."

That is true.