World At Their Feet

Cricket

ICC 50-over World Cup: May 31-July 14, 2019; England and Wales

The balcony at Lord's is of great significance to Indian cricket, and to the state of the world game as we know it today; its economics, its geofences, its subcontinental mania. For, on 25th June, 1983, on a cloudy afternoon in central London, had Kapil Dev not stepped on to the balcony's verandah with his perma-grin (all poise and teeth), followed closely by the rest of his World Cup winning teammates (one of them crowding the claustrophobic space was opener Krishnamachari Srikkanth, gloriously sucking away at a cigarette), cricket would not have transformed, irreversibly, from an elite pastime to mass entertainment in India. Kapil then held aloft the Prudential Cup and the image birthed everything from Sachin Tendulkar to the Indian Premier League to the BCCI's autocratic control of the sport.

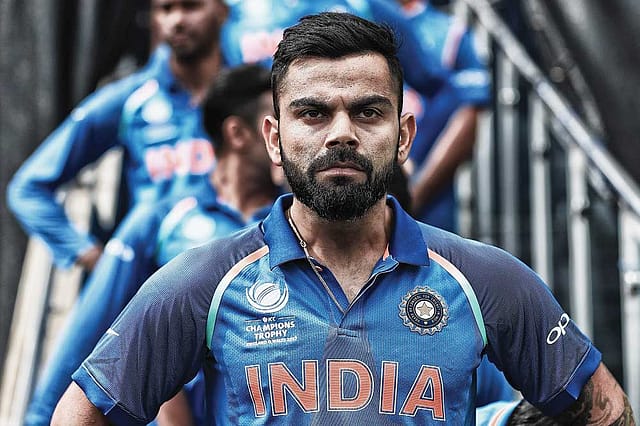

Thirty-six years later, the stage, and the balcony, is set for Virat Kohli—an offspring of Kapil's creations, for he is a reincarnation of Tendulkar, the face of modern-day cricket and the invisible commander-in-chief of the Indian cricket board—to sow the seed for a new revolution. And if he's stood at Lord's on 14th July this year, holding a World Cup, Kohli would have become only the third Indian to be called a World Cup-winning captain and second Indian player (along with MS Dhoni) to win the trophy twice. Between Kohli and immortality stand nine teams, all of which India will face in the space of 32 days during the group stage. The last time a 50-over World Cup pitted every team against every other before the table's top-four made the semi-finals, the 1992 edition in Australia and New Zealand, it produced arguably the most memorable World Cup of them all, what with the current Prime Minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan, triumphing against all expectations, including his own.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

Kohli's India are far from Cornered Tigers (as Pakistan of '92 came to be known). They go into the tournament with the baggage of being favourites, equipped as they are with the best top- order batsmen (Rohit Sharma has three ODI double hundreds; Kohli, as of now, has 38 ODI centuries) and the finest bowling attack—a delicious and perfectly balanced mix of wrist spinners (Kuldeep Yadav and Yuzvendra Chahal) and death bowlers (Jasprit Bumrah and Bhuvneshwar Kumar). Yet, of course, simply being a great team does not guarantee India success, not when any given side is 11 matches away from the trophy.

India—and most Indian fans will be surprised by this—aren't the only team at the World Cup with aspirations. Many eyes and hopes will be pinned on India's first opponents in the group stage, South Africa, who, incredibly, haven't gone past the semi-final stage of a 50-over World Cup despite being the best team at a given edition, time and again. And home conditions and support should count for something in England's—a vastly improved ODI side in the last few years—bid to break their duck.

Don't rule out Australia, a team under transition, either. Not just because they are defending champions but because this is a World Cup, and Australia always play their best short-format cricket at one. The last time a World Cup was played in the UK, back in 1999, it was Steve Waugh who was stationed atop that iconic balcony, ushering in one of the most dominant eras in cricket; an era in which Australia won four out of the last five World Cups.

Tennis

Davis Cup: November 18 -24, 2019; Madrid, Spain

For as long as anyone can remember—because that's how far back the sport's greatest era stretches—the build-up to a fresh tennis season, which coincides with the beginning of a calendar year, revolved around the physical fitness and off-season preparations of the game's all-time superstars: Roger Federer, Rafa Nadal, Novak Djokovic and Andy Murray. This forecast was largely predictive, positive and controversy-free. And then came 2019, a year that threatens to rip apart the players and the fans into factions, and also destroy what has been a harmonious relationship between them and the game's sponsors.

After 118 editions, the tried and tested format of the Davis Cup— tennis' only international team competition of worth— has been forced to change. For over a century, the competition was played alongside the regular season, in a home-and-away format, all around the globe and during intermittent windows between the big tournaments. It was held in every country that has heard of tennis and discovered heroes who always rose to the occasion while rallying with their nation's name on their shirts (read Leander Paes, a Davis Cup legend). But the ITF, tennis' governing body, wanted to keep up with the times and hired Kosmos, a fledgling investment group headed by former Barcelona defender Gerard Piqué, to drive in the reforms. The result? A one-week, one- venue play-off between 18 countries at the end of the tennis season.

An upset Federer remarked that the Davis Cup had become the 'Piqué Cup', adding: "It's a bit odd to see a footballer arrive and meddle in the tennis business." He has since made himself unavailable for the Finals Week in Madrid, which will take place at the end of the 2019 tennis season in November. But for every Federer there is a Nadal, who has backed the venture and promised his participation. Some see the move as a facelift. To others, it is a botox job gone wrong. However one chooses to look at it, the change has got more people talking about the Davis Cup than ever before, which, for Piqué and Kosmos, could well be half the job done. Every tennis fan and player has an opinion on it and that's also why, come November, all eyes will be on it.

Badminton

BWF World Championships: August 9-25, 2019; Münchenstein, Switzerland

No Indian has worn a gold medal around his or her neck in the 24 BWF World Championships held so far, dating back to 1977. Not in singles (men's or women's) and not in doubles (men's, women's or mixed). But over the last three years, Indian badminton took larger strides towards the top step of the podium than all the previous years combined, thanks to two girls who have become synonymous with the sport itself in this country: PV Sindhu and Saina Nehwal. For, in 2018, 2017 and 2016—at Nanjing, Glasgow and Jakarta, respectively—either Sindhu or Saina found herself one match away from ending the drought.

This is the golden period of women's badminton worldwide, and, hence, for Indian badminton as well; the renaissance ushered in by Sindhu and Saina—top rankers, global superstars, household names (in the Forbes list of richest Indian athletes in 2018, Sindhu was ranked fourth). Both have medalled at the Olympics, both have a fistful of Super Series titles, and both have finished runner-up to the eventual winner of the World Championships. In the 2016 and 2018 finals, Nehwal first and then Sindhu lost in straight games to Spain's Carolina Marin, the undisputed leader in this era of glut. But it was in the year between those losses, 2017, in Marin's absence, that the meaning and the scope of the World Championships was truly understood.

For 110 minutes in Glasgow, Sindhu and Japan's Nozomi Okuhara appeared in what is widely considered the greatest women's match ever played. Sindhu matched Okuhara stroke for stroke and point for point, only to lose out (and because this is badminton) by a feather. Some say Sindhu has never mentally recovered from being so close and some say that the easy loss in 2018 proves the fact. But some also say, especially in sport, that athletes tend to get third-time-lucky and for Sindhu, 2019 in Münchenstein, Switzerland, could be that place and time.

Rugby

IRB World Cup: September 20 -November 2, 2019; Japan

Every four years, for about a couple of months and mainly during weekends, the world wakes up to a sport and tournament predominantly played, headlined and won by countries that lie south of the equator: the World Cup of rugby. Of the eight World Cups held so far, only one country from the northern hemisphere has won the trophy: England—the inventors of the game. The rest have been neatly shared by three nations: South Africa (2), Australia (2) and the country where the soul of this sport resides, New Zealand (3), who would not like to be denied a fourth Webb Ellis Cup on 2nd November, 2019, in Yokohama, Japan.

New Zealand, or the All Blacks as the team is known, won the last two editions, played at home (2011) and England (2015), but a third straight win this year—as expected by the quadrennial fairweather fans—may not be taken for granted, given their recent form. In 2018, they lost a Test to the Springboks (South Africa, who will be in the same pool as NZ in Japan) in their fortress at Wellington and then to Ireland, giving Steve Hansen, All Blacks' Cup-winning head coach, plenty to mull over.

If the pundits are to be believed, then the smart money to win the ninth edition could well be on Ireland, a team that has never reached the semi-final of a World Cup. Yet. Last year, the metamorphosis from also-rans to genuine World Cup contenders took place as Ireland, under coach Joe Schmidt, beat the Wallabies (Australia) in their backyard to win a Test series and also the Six Nations. But all that wouldn't have made a dent to the punditry had they not defeated the All Blacks in Dublin and thrown a gauntlet all the way to Japan.

Football

English Premier League: January 1-May 12, 2019; England and Wales

Since England's top flight football was rebranded the English Premier League in 1992, Liverpool FC—the most successful club in not only England but all of Europe at that point, with 18 titles— haven't won the league. For the Liverpool fan, and there are many millions of them globally, this is a rather depressing statistic. Not only have their arch rivals, Manchester United, overtaken Liverpool's tally with 20 league titles (13 of them having been achieved in the post-Liverpool era); the Anfield die-hards also have to live with the fact that there are, among them, 29-year-old men and women who have never in their lifetimes witnessed their club topping the table at the end of a season. That, however, could well change over the next few months.

Miracles do occur in the EPL, as Leicester City proved in the 2016- 17 season by beating the mightiest odds (2000:1) and winning the league. Unlike Leicester, Liverpool have a great squad, an incredible manager at the peak of his powers, Jürgen Klopp, a global superstar in Mo Salah and, most measurably, a nine-point lead over second- placed Tottenham Hotspur at the end of December. Yet, a Liverpool win will nevertheless be considered a miracle, for the same reason that Boston Red Sox's World Series win after a wait of 86 years was received as one; a globally loved team had killed off a decade-long curse. But monkeys tend to cling to backs, and the Reds know of the burden of rewriting history better than most football clubs.

Twice in the last 10 years, in 2008-09 and more recently in 2013-14, Liverpool entered the second half of a season—into the January of the new year—in the lead and promptly blew it. Both Tottenham, a club that has never won the league, and Manchester City, a club that has taken over the baton of perennial favourites from their city rivals, will live in the hope that the incumbent leaders stumble during the home stretch, on or before May 12th, 2019. This has all the makings of one of the finest seasons, football- wise. But were Liverpool to win, it will be a season to cherish for millions, and remember for all.