Ruin of the Congress

As two recent books tell us, India's most charismatic leader, Indira Gandhi, has left a debilitating effect on the party.

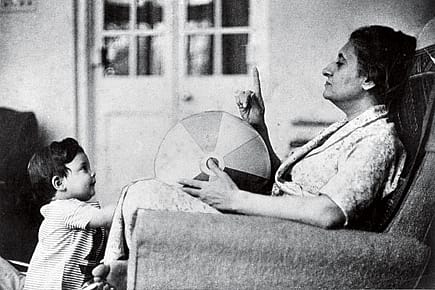

In 1970, Indira Gandhi became a grandmother. In August, she wrote to her friend Dorothy Norman, 'My grandson Rahul is a darling. He has got rid of his wrinkles and still has his double chin.' Rahul Gandhi was little able to make sense of what was going on around him at the time, but if he now looks back at the history of the Congress party, he'll find that the need for the unfruitful struggle that he is waging within it is a result of the years preceding his birth, when Indira Gandhi took charge of the country after Lal Bahadur Shastri's death in 1966.

In the story of Indira Gandhi, too much attention has been paid to the highlights—the nationalisation of banks, the war on Bangladesh, the Emergency, the triumphal return, the death of Sanjay Gandhi, Operation Blue Star and her assassination. But the real story lies in the intervening years, in the gaps when her insecurity fanned a messianic delusion that saw the destruction of almost every institution that her father had nurtured, including the very Congress party that her grandson is today seeking to resuscitate.

The release of Nayantara Sahgal's book on Indira Gandhi, published abroad in 1982 but never in India, and Aarthi Ramachandran's book on Rahul Gandhi, the second such book after one by Open's Jatin Gandhi, is perhaps the right time to look at the fate of a party undone by one of its most charismatic leaders, and the largely ineffectual attempts of her grandson to undo the damage caused.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The book by Sahgal, Vijaylakshmi Pandit's daughter and thus Jawaharlal Nehru's niece, is not the work of an academic or a political analyst. Bias is inherent in the project. Indira Gandhi distanced herself from her aunt's family shortly after Nehru's death, but for that very reason Sahgal the author does not buy into the mythology of Indira Gandhi, built in no small measure through her own exaggerations.

Sahgal notes, 'As prime minister, Mrs Gandhi told public meetings she had often faced bullets in her life, provoking a journalist to comment tartly, "If she did face bullets, it might have been in an unchronicled, unsung chapter of her much publicised life." The publicity, however, depended almost entirely on her own statements, there being no other source for much of the material making its appearance in written accounts about her. She frequently charged the Jan Sangh with trying to kill her, an accusation she had to withdraw when Jan Sangh MPs took it up in a stormy meeting of the Parliamentary Consultative Committee of the home ministry, and she admitted she had no evidence for such a statement…. Of her only imprisonment, from September 11, 1942 to May 13, 1943, in Naini Central Jail, Allahabad, she told an interviewer in 1969, "I was regarded as so dangerous that I wasn't even given normal prison facilities"—a recollection not supported by the evidence of the time. Mrs Gandhi, aged nearly twenty-five, shared a barrack with her aunt, Mrs Pandit, her cousin, Chandralekha Pandit, aged eighteen, and a number of women friends and acquaintances, all subject to the same rules and regulations. Mrs Pandit writes in her preface to the prison diary she kept, 'The treatment given to me and to those who shared the barrack with me was, according to the prison standards, very lenient.''

As became clear in the lead up to the Emergency, Indira Gandhi was completely capable of acting on her own delusions. She may even have convinced herself that the threat to her life and the country was real, irrespective of the lack of evidence. This delusional and self-serving nature of Indira's recollections may have been an intrinsic part of her personality, as noted by Nehru in a letter written to Vijaylakshmi Pandit from jail when Indira was only 15, 'Indu, I feel, is extraordinarily imaginative and self-centered or subjective. Indeed, I would say that, quite unconsciously, she has grown remarkably selfish. She lives in a world of dreams and vagaries and floats about on imaginary clouds, full probably of all manner of brave fancies. Now this is natural in a girl of her subjective nature and especially at her age. But there can be too much of it and I am afraid there is too much of it in her case… I feel she requires a course of field or factory work to bring her down from the clouds… She will have to come down, and if she does not do so early she will do so late, and then the process will be painful.'

It was painful, not just for her, but for the party. When she took on the Syndicate, the established leadership of the Congress which wielded enormous influence within the organisation, it was because she felt her authority had been challenged. Her father had acceded to the wishes of the organisation in supporting Rajendra Prasad for the post of President. Indira was unwilling to do the same where Neelam Sanjiva Reddy was concerned. Her support to VV Giri ensured the election became a direct contest between her and the party organisation. She won, and that ensured the destruction of the party.

In the next few years, she virtually reduced the organisation to its present state, 'An atmosphere of fealty, feudal in texture, descended on the Congress. Her colleagues and associates, with few exceptions, had no political bases of their own and were dependent on her for their positions. Nehru had been surrounded by an aura of deference, even reverence, but his ministers had been personalities in their own right, some of them powerful and impressive men. The contrast extended to the secretariat. Nehru, often impatient and short-tempered, tended, all the same, to support his civil servants, and they were sure of the ground beneath their feet. The government's intentions and objectives were known. Mrs Gandhi's lack of a defined philosophy left those working with her in uncertainty. There was no clear-cut framework within whose rhythm and logic they could take decisions without getting clearance from her, no orchestration of men and ideas to produce teamwork. There was an ad hocism, a compartmentalisation of subjects and long delays in making senior appointments that often lay vacant for months. And with Mrs Gandhi's instinctive antagonism to criticism, known or suspected, only a show of loyalty guaranteed a career.'

With the destruction of the party organisation came ideas such as a committed, read servile, bureaucracy, the manipulation of judicial appointments in the hope of subverting the Judiciary, and the attack on a free press. We are still living with the results.

In 2006, Aarthi Ramachandran recounts, Rahul Gandhi spoke at the 82nd Congress Party Conclave about the 'party's problems in states where it had become "weak". He chose UP as an example and pointed out that the Congress failure there had been organisational rather than political. "We have failed because we lost that ability by which we could bring forward the true worker of the Congress," he said, asking the party to give "the anonymous mass of workers" a "voice in the organisation". The difference between a "true leader" and a "neta" or powerful politician, he stressed, was that—the former would have to be built "brick by brick" as there was "no fast path to success in creating leaders".'

He could well have been quoting his great-aunt, who, in her introduction written in 1982, had noted that 'this book originated with a paper I was asked to contribute on Indira Gandhi's political style for a conference on 'Leadership in South Asia'… It traces the events in the Congress party and the country that represent a break with the style that had been a feature of the historic Congress.'

'Congress politics had worked within the framework of democratic institutions, encouraging open and diverse expression and debate both within the party and between the ruling party and the Opposition. Indira Gandhi's creation of a highly centralised governing apparatus and party machine under her personal command had the effect of reversing this process.'

The problem that Rahul Gandhi now faces, as becomes clear from Aaarthi's account, is that it does not suffice to reverse this process. Rahul has focused his energy on trying to rebuild the party organisation, starting with the Youth Congress and the NSUI. Typical of his background in management, he has concentrated on a structural solution, deliberately forgoing any attempt to create a politics of personality around him.

But this is to pretend that Indira Gandhi never happened. She has left a Congress behind that can only be held together through the force of personality, and which needs a personality-driven campaign to contest elections. Thus, the bewilderment that surrounds Rahul in the party when he says he is the long term. As far as party members are concerned, there is no long term; the party cannot hold together if it does not partake of the spoils of power every few years.

If Rahul has to succeed in changing the party, he has to reverse his priorities. It is only when he can demonstrate that he can lead the party to victory in elections that his attempts to change it from within will be taken seriously. Right now, they are seen as indulgences granted to a Nehru-Gandhi heir to keep him occupied while he makes up his mind about his political future.

This is clearly lost on Rahul and on men such as Kanishka Singh and Sachin Rao who surround him. They speak the language of modern management, given their corporate background and training. It is no wonder their ideas are so ill-suited to the political environment that Indira Gandhi has left behind as her legacy. Management, by its very nature, demands a set of skills that work equally well while selling soaps or shoes, and these may help in setting up an organisational structure, but they ring hollow when they are brought in to define the message a party must project.

In UP, the Congress faces parties such as the BSP and SP, whose support base is clear and whose programmes are built around this fact. The Congress, which hopes to reach across fixed support bases, then needs to begin by articulating ideas that resonate, not fixing organisational structures. We still have no idea what Rahul Gandhi stands for, what he believes in, what he will not tolerate, what his priorities are for a Congress government.

If not in this election, then in the next, the Congress will have to meet the challenge of a Narendra Modi, who brings the same authoritarian impulse and charisma that Indira Gandhi embodied, even if she cannot ever be accused of the kind of communal politics he thrives on. Polls show that she continues to be seen as our most popular Prime Minister. Obviously, people pay little heed to the reality of what she wrecked in this country. It is likely to be much the same with Modi.

Indira Gandhi showed that the politics of personality can override the strongest political organisation this country has ever seen. There is little chance that Rahul's rag-tag Youth Congress and NSUI can head off a Modi who, if anything, might be countered by what we hope is the innate good sense of voters in this country—which admittedly failed to stop Indira Gandhi.

However, it would help if Rahul could articulate a vision that people could respond to, stand for ideas that are worth fighting for, rather than try and indulge in Bandaid repairs of an organisation that is almost dead. It is only through his success that he can begin the reconstruction of the Congress. Unfortunately, the possibility looks very remote today.