Who Is Charles Sobhraj?

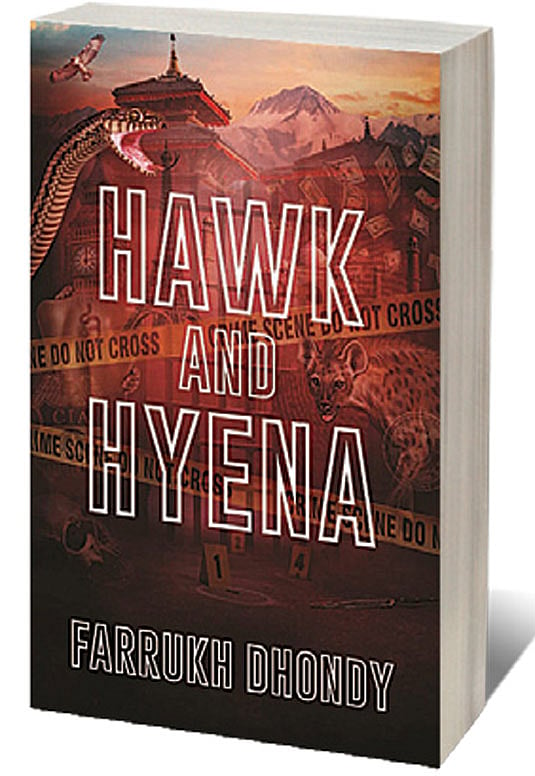

A PRECISION HUNTER? Or an odious brute? Hawk or hyena? Farrukh Dhondy’s principal question on the identity of an alleged serial killer appears deceptively simple. As the pages in the book turn, one thing becomes clear. Questions on identity and essence are a complicated exercise. But the answers become more elusive while investigating a person like Charles Sobhraj, who few really know and, that too, only in “bits and pieces”.

Two tensions in the narration turn this puzzle into a riddle and then into an enigma. The first one is Sobhraj’s tense tightrope walk into his past, whenever he is asked about it. Sobhraj is keen to boast about his sordid life, but he is also wary that too much information can incriminate him. Dhondy notes Sobhraj’s “ambivalence about being a killer and the uncertainty about how famous a killer”.

His own fears aside, Sobhraj, perhaps, sensed the kind of story people wanted to hear and he tweaked his narration accordingly. He is boastful before the gullible listener, but sober and more candid with the hard-nosed Dhondy.

The other tension running through the book comes from within the author himself. Dhondy is keen to demonstrate to the readers that he knows Sobhraj well enough to chronicle a memoir. He is also anxious to inform the readers that he harbours no moral ambivalence about the subject. Dhondy makes his disapproval, and at times his dislike, of Sobhraj clear. These tensions will captivate even those readers only somewhat familiar with Sobhraj.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Dhondy’s anxieties are most pronounced when he takes Sobhraj to meet a former CIA employee. The author wonders if he needs absolution for his association with a killer. He tells himself that he should not be sharing in guilt, which is not present within the actual killer. Yet, Dhondy is unable to sever ties for once and for all. For years, he keeps answering Sobhraj’s calls to get his whole story.

At times, Dhondy’s scepticism can infect the reader, who may speculate whether Sobhraj is a master criminal or an accomplished storyteller. For instance, in the ’80s, Sobhraj captured the Indian media’s imagination with the story of his daring jailbreak from Tihar that involved drugging the guards into stupor. Years later, Dhondy finds that the story was run-of-the-mill bureaucratic greed—a few prison officers facilitated the escape for a bribe.

While Dhondy’s patient unearthing of the truth is commendable, sometimes complicating the questions around a subject makes for a better read than answering them. Had Dhondy woven a maze of intriguing questions around Sobhraj, the book could have seduced critics far more than, say, the widely panned OTT series on the man.

Overall, Dhondy’s occasional perspectives and idiomatic ease in writing multiply the attractions of this book. However, his narration may leave the reader searching for context.

In Agra, Sobhraj spots a group of French tourists discussing gems that could be purchased in north India. Sobhraj befriends them and executes a complicated plan to rob them. The scheme ends in disaster for the hunter. Dhondy had an opportunity to provide a backdrop to this story. Why were the tourists interested in buying gems from India? How was the global trade in gems conducted at the time?

Answers to these questions could have helped readers understand why the tourists fell for Sobhraj’s ruse in the first place. When Sobhraj spotted this opportunity, it was likely based on some knowledge of this trade and the inclinations of European tourists in India. The most interesting biographies are after all those in which, as the American anthropologist David Mandelbaum said, we see “how the person copes with society rather than how society copes with the stream of individuals”. Mandelbaum’s acuity came from his study of Mahatma Gandhi. The insight may apply equally to a saint and a scoundrel.