The Son’s Rise

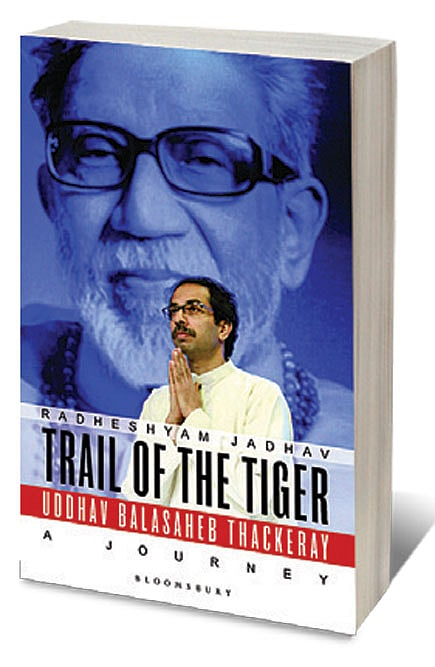

ANYONE WHO REMEMBERS the Shiv Sena of the 1990s, when it was at its peak, having captured power in Maharashtra, will be hard put to place Uddhav Thackeray among those identified with the party’s leadership. After its founder Bal Thackeray, there was his nephew Raj. There were the two chief ministers not hailing from the family. Uddhav was so low-key that even his sister-in-law, Smita Thackeray, was more in the public eye than him. But within half a decade of the new millennium, the party was entirely under his control. Radheshyam Jadhav’s biography, Trail of the Tiger, Uddhav Balasaheb Thackeray: A Journey, informs us that Thackeray’s importance in the party had been increasing from the early 1990s onwards but even Raj, who was at that point perceived as the successor to Bal Thackeray, hadn’t foreseen how much the direct bloodline helps in politics.

Jadhav tells a neat orderly story of Uddhav’s rise. If you are looking for the grime hidden in the corners of a political dynasty, this is not that book. It offers no secrets than what has been in the public sphere. But he does thread it into a coherent narrative. What you get is not the inside story but an overview that comes with its limitations. For instance, Uddhav, when he took over the chief ministership, said that it was with reluctance and at the insistence of ally Sharad Pawar. It is a story that Jadhav repeats. But was there really an option to do what Bal Thackeray did—exercise the remote control while not taking the seat of power himself. The father’s power was absolute because he pulled in all the votes and was venerated by party workers. Without that position, giving anyone else chief ministership means propping up a potential contender.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Even without scratching too far below the surface, Jadhav’s account is still a readable one because Uddhav is a politician of interesting contradictions. There is the striking contrast with his father, who turned sarcasm and perceived historical slights to draw hordes of Maharashtrian youth.

Uddhav is the refined next generation, a counterpoint to all that the Shiv Sena was unabashedly proud about for decades—regionalism, communalism, street violence. Under him, the rough edges have been smoothened, reflecting the man himself. This might not necessarily have had a happy ending and it still might not. But, the story of Uddhav is essentially his continuing survival when most felt the Sena’s gradual decline into being a bit player was a given. As Jadhav writes: ‘[H]e had little oratorical skills and was not known for his leadership capabilities. He was accused for benefitting from his father’s position and his wife’s ambition. It was predicted that once the memory of Balasaheb’s persona faded from public memory, he would fail. But it is clear today that the Sena has grown stronger under him.’

But is the Sena really stronger? Its seats have been coming down in succeeding elections but, on the other hand, it has become alive again. As Jadhav says in the book, the BJP has a history of cannibalising allies into irrelevance but usually they can’t do anything about this. Uddhav’s triumph is in essentially putting a stop to that while propelling himself into the chief minister’s chair. We don’t know the long-term story but he has won this round and remains in the game. He still has to figure out what his party will stand for. Jadhav writes, ‘The Sena’s old guard strongly believes that Uddhav’s experiments with reformist Hindutva will end the day his political experiment with the NCP-Congress ends. What will he do with his father’s dream of setting up the Hindu Rashtra, starting from Maharashtra?...His answers to these questions would depend on the lessons he learns as the chief minister of the Sena-NCP-Congress coalition government.’