The End of Immunity

Austrian-American historian and preeminent Holocaust scholar Raul Hilberg never asked the big questions because he was afraid the big questions would get small answers. He focused on the minutiae, looking at the how, avoiding the why. Proceed vertically, not chronologically, he might say, and then like a geological study, you would get a cross-section of what happened. There may be half-answers to the big questions by the end, but that’s not the point. The pursuit is the detail that establishes the truth.

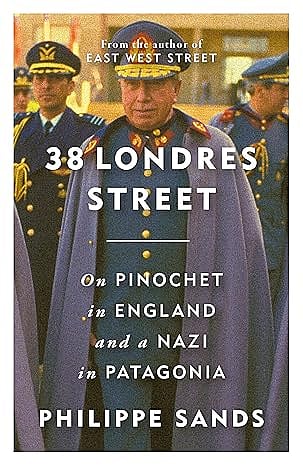

Philippe Sands, writer and international lawyer, is a master storyteller. 38 Londres Street is the conclusion of a trilogy that began with East West Street: On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes against Humanity (2016) and continued with The Ratline: Love, Lies and Justice on the Trail of a Nazi Fugitive (2020). 38 Londres Street intersects two narratives: former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet Ugarte’s arrest in London on a medical trip in October 1998 and attempts to extradite him to Spain to stand trial for crimes of mass murder, torture and disappearances committed by his regime after the September 11, 1973 coup that deposed President Salvador Allende; and the refuge given in Chile to SS officer Walther Rauff—the inventor of the mobile gas vans that murdered 90,000 European Jews before the death camps became operational—and his alleged links to Pinochet’s regime and participation in the Chilean chapter of mass murder.

There is a third narrative: Pinochet’s was the first instance of a former head of state arrested in and by another country for “international crimes” at the request of a judge in a third country. This was before the International Criminal Court (ICC) was founded; long before Rodrigo Duterte’s extradition on an ICC warrant in March 2025, or calls for the arrests of Vladimir Putin and Benjamin Netanyahu. Slobodan Milosevic’s trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) doesn’t count because the ICTY, like Nuremberg, was a special tribunal. The Pinochet case, therefore, set a precedent in redefining the contours of immunity for a former head of state under international law.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In East West Street, Sands studied the destruction of Lviv (Lemberg) and its Jewish community; the end of his grandfather’s family in the Holocaust; and how two Jewish lawyers, Hersch Lauterpacht and Raphael Lemkin, survived to define genocide and crimes against humanity at Nuremberg. These were new legal concepts. In Ratline, Sands pursued the story of Otto von Wächter, a high-ranking SS officer and Nazi governor of Lviv/Lemberg on whose watch the author’s extended family had perished. Wächter died in mysterious circumstances in Rome after the war while awaiting a passage to South America on the advice of his friend Walther Rauff. The books interrogate denial and the tendency to move responsibility up the chain of command. Ratline is also a study in the complicated inheritance of the children of war criminals, and the clash of personal memory with historical perspective.

The title of 38 Londres Street refers to the former headquarters of the Socialist Party in Santiago—Londres 38—which was turned into an interrogation and torture chamber by the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA), the first avatar of Pinochet’s security service under Manuel Contreras. The agency undertook repression on an industrial scale and built a concentration camp in Tierra del Fuego. It also used a colony of Germans, established by the paedophile Paul Schäfer, another Pinochet loyalist, to bury bodies. DINA’s orders would have codes indicating land burial or sea burial. The sea burials happened off the coast of San Antonio near Valparaiso and there are allegations, never proven, that many corpses were turned into fish meal and chicken feed. The Pinochet regime found one ethnic group very useful, especially those among them who were mid-century émigrés running from their past. These men had special knowledge of interrogation, torture, prisoner transport, killing techniques, and disposal of corpses.

Sands was asked to be Pinochet’s counsel after his arrest. His wife threatened to divorce him and he ended up on the other side, working for Human Rights Watch, one of the groups submitting evidence against the former dictator. In due course, Sands discovered a personal connection again—his mother-in-law was related to Carmelo Soria, a UN diplomat from Spain tortured and murdered by the regime in 1976, whose case became one of the pivots for Spanish Judge Baltasar Garzón’s request for Pinochet’s arrest and extradition. It took the UK’s highest court two judgments to decide the question of immunity, with Chile’s democratic government arguing that Pinochet be returned home to stand trial. Home Secretary Jack Straw authorised the extradition but deals made at 10 Downing Street by Prime Minister Tony Blair’s Chief of Staff Jonathan Powell (currently Keir Starmer’s National Security Adviser) stopped the extradition. Pinochet returned to Chile, cheered by Margaret Thatcher, pretending to be old and infirm in a wheelchair, the act ending—as the world watched—once he landed in Santiago and greeted his supporters.

Sands’ pursuit of Rauff, a man who appears in various avatars in Roberto Bolaño’s works as well as Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia (1977), is structured like a thriller. This is real detective work and it takes years for Sands to establish the connection between Pinochet’s regime and the Nazi—something accepted even by taxi drivers in Chile but which never threw up a shred of credible evidence. Another personal connection: Sands’ aunt Herta, his mother’s cousin, and her mother were among the 90,000 killed in Rauff’s gas vans.

Pinochet denied he knew Rauff but that was a lie. They had got to know each other in Ecuador in the 1950s. In fact, Rauff had moved to Chile on Pinochet’s advice. He lived openly, managed a crab cannery in Punta Arenas in Chilean Patagonia. He celebrated Hitler’s birthday every year, worked at a time for both the West German BND as well as Mossad, neither agency seeming to know whom it had recruited. Under Pinochet, Rauff called himself a “protected monument” in a letter. But as early as 1962 Chile had refused to extradite him to West Germany in a decision supported by Allende. A disgusted Pablo Neruda had written: “I cannot deny that this man understands vans… Nor can I deny that my country’s justice system has a well-adjusted conception of reality: it protects those who efficiently organise mass murder and the use of vans.”

Vans were used to transport prisoners and corpses. These vans belonged to another cannery, near San Antonio. A former detainee at Londres 38 had heard a man speak bad Spanish with a German accent but couldn’t see him through his blindfold. There would be other accounts but that this man was Rauff was never established with near-certainty before Sands came into the picture and cross-checked evidence from former DINA conscripts still testifying against the Pinochet regime in Chile’s courts.

Pinochet died in 2006. Rauff died in 1984. Neither man was tried for his crimes. Both enjoyed impunity till the end. But after Pinochet, immunity for former heads of state/government hasn’t been the same. And Rauff would have hanged at Nuremberg anyway. Antony Beevor calls Sands “phenomenal” and not without reason. A lesser writer would have lost the reader in the legal labyrinth of the Pinochet case. Sands is subtle and understated. He doesn’t show emotion despite his personal involvement and family history. All he cares for is the incidence and chain of evidence. The Hilberg detail that makes the case.