The Doubting Believer

The cover of Urmilla Deshpande and Thiago Pinto Barbosa’s Iru: The Remarkable Life of Irawati Karve bears an illustration, a portrait of Dr Karve, India’s first woman anthropologist. Stars are scattered across Karve’s saree, and stars, too, adorn the top half of the cover. Food for thought: Irawati Karve, after all, though a scientist, was no astronomer. This was a woman who spent her life studying people: trying to understand what made Indians, especially, who they are. Stargazing, in the sense of daydreaming, does not seem to have been one of her traits. And though, by defying her own family and going abroad for higher education, Irawati showed that she could reach for the stars, there’s more to it.

Near the end of the book, co-author Urmilla Deshpande (Irawati’s granddaughter, the daughter of her youngest child, Gauri) explains that her grandmother loved wearing sarees. Because Irawati was quite tall, she had to have her sarees specially woven for her: store-bought sarees were too short. These bespoke sarees would be decorated, according to Irawati’s wishes, with screen-printed stars. Are the stars on the cover a continuation of that saree pattern? Or a subtle reminder that Karve was a star too? Also, one who, while she had her feet firmly on the ground, could look up and beyond? Both philosopher and scientist, both believer and doubter?

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

This duality is, appropriately enough, a hallmark also of this book about Irawati, ‘Iru’, as she was affectionately known. Deshpande and Barbosa, the former a writer of fiction and the latter an anthropologist, bring to this work their own areas of expertise, their own perspectives. Thus, as they begin the book with the 22-year-old Iru’s sojourn in Berlin, pursuing a PhD and

measuring human skulls to test her guide Eugen Fischer’s theory of eugenics, we have solid science showing us what Iru was expected to do, and how she went about it. But we have, too, a weaving in of a story: how a lonely Iru, an Indian woman in post-Great War Germany, might have felt about the racism, the disturbing signs of the Nazism that would take root within a few years.

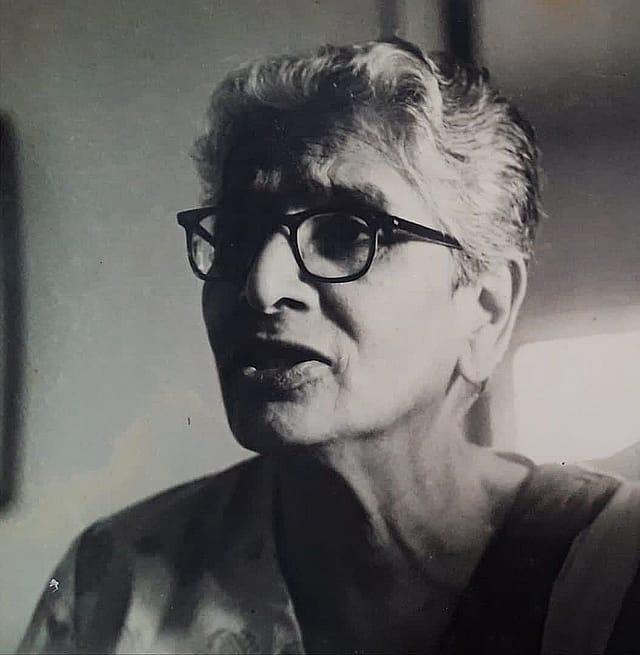

The balancing of professional and personal, of the scientist and the philosopher, the wife and the mother, is a theme that runs through the book. Iru traces Irawati’s childhood, first in Burma as the daughter of expatriate Maharashtrians, and then in Pune, where she was sent for her schooling and ended up becoming foster daughter to ‘Wrangler’ RP Paranjpye, the mathematician. From Iru’s marriage to Dinkar ‘Dinu’ Karve to their children, from Iru’s first stint in Berlin to subsequent journeys to Europe and America, to field trips across India: the story of Iru’s life builds up vibrantly.

The anecdotes that give us a picture of Iru’s work are fascinating, ranging from unusual bits of trivia relating to field trips, archaeological digs, interesting communities she studied, and so on. Equally insightful are the glimpses we get, alongside, of the philosopher Iru was. The woman who loved trees and birds and animals. Who could look at a millennia-old human skeleton and feel a connection to it. Who was well-versed in literature (and used literature to help interpret what she saw in human societies she was studying). A woman who wrote extensively not just on science but on the Mahabharata too. A scientist, rational and level-headed. But a believer, too.

This duality of Karve’s nature is built up with sensitivity through the book. Deshpande and Barbosa’s writing meshes mostly well, though there are moments when one can imagine (perhaps) which of the two authors has written which part. The picture that is built up is of a courageous, curious, highly intelligent woman with an insatiable sense of curiosity and a determination to forge her own path. A truly remarkable woman, indeed, and deserving of the tribute that this book offers her.