The Constant Migrant

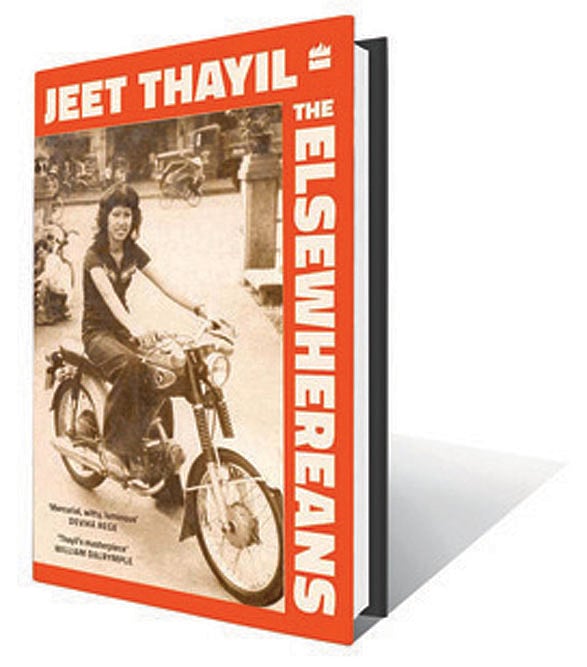

MOST SUCCESSFUL AUTHORS find a formula that works for them and their readers, and stick to that. But Jeet Thayil is not one to succumb to an oeuvre. With each book, he seems to pull a new creature from his hat. And those who follow his work can only gape and exclaim—now what? With The Elsewhereans (Fourth Estate; 221 pages; ₹699) he does just that. Classified as a ‘documentary novel’ it veers away not only from easy labels but also from his previous works.

With The Book of Chocolate Saints (2017), Thayil proved that he could write the ‘big Indian novel’—peopled with desolate poets and broken artists, determined journalists and feisty women. He changed register and completed his Bombay trilogy with Low (2020), a harrowing tale of bereavement and a search for oblivion. Next came Names of the Women (2021), a novel about the women whose roles were reduced or erased from the Gospels. Thayil has never shied away from plumbing the material of his life for fiction. His debut novel Narcopolis, which was shortlisted for the 2012 Man Booker Prize, drew from his drug-addled years in Mumbai. Low plunged into a personal tragedy. Names of the Women borrowed from his years growing up in a Malayali Christian household. In his previous books fact and fiction met like ink and water, each swirling within the other, creating wondrous patterns. In his most recent work, he pushes the same premise farther.

In The Elsewhereans Thayil comes home, and we meet his closest relatives, his parents. Writing about lovers and partners is often an exercise in self-examination. But to write about parents is an act of exhumation. One’s childhood—however fraught or fun—can be examined only at one’s peril, as a parent-child relationship is an intrinsically unequal one. In his writing and persona, Thayil can never be accused of sentimentality. He brings not only a realist’s understanding to his material, but an anatomist’s. With The Elsewhereans his gaze burns into his parents (Ammu and TJS George) and his ancestral land (Kerala).

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The Book of Chocolate Saints and Names of the Women in some ways presumed a prior knowledge which risked alienating a lay reader. The Elsewhereans is his most relatable book to date and his finest. Relatable, not because it is simple, but because it is universal, as Thayil spreads his canvas wider. He tells us we all belong to Elsewhere, and that the Elsewherean is worthy of celebration.

I consumed the book in less than two days. Even though it is autobiographical its power lies in how many a reader will say: this is my story. We are now at a time when where you are from is who you are. It is a time when to be a migrant is not to be a wanderer but an interloper. A time when parochialism is a badge of honour and cosmopolitanism a threat. At such a time Thayil’s The Elsewhereans serves as a rallying call. It is an anthem for migration. It is a paean to movement. He reminds us that movement is central to both the Bible and the myths. All great literature is one of two stories (as Tolstoy said), “A man goes on a journey; or a stranger comes to town.” Both work on the premise of displacement. Without movement what stories would we have? Humans were never meant to stay in only one place. To move is to not only explore, it is to evolve. This movement (which is relocation and not tourism) might reconfigure one’s sense of self, but it is movement that propels the human story. Movement takes one to Elsewhere, and movement makes one Elswhereans. Thayil tells us that Elsewhere can be a “spiritual calling”, and that freedom is the only patriotism and internationalism is the true nationalism.

The book might move from Kerala to Bombay to Paris to Hong Kong, but it maps more than geographies. It is a book where Elsewhere is both place and condition. A book that says authors are always migrants, as they travel from this world to the one of the imagination. A book which reminds us that ‘Death’ is the ultimate Elsewhere. A book which found its natural ending with a death.

It was originally titled ‘Melanin’. Rahul Soni, the book’s editor had suggested ‘Elsewhereans’ and Thayil resisted the suggestion until a few months ago when it struck him that ‘Melanin’ implied limited circumstances, whereas ‘Elsewhereans’ was multidimensional. He says that ‘Elsewhereans’ is more open to interpretation, and it is “the correct title for a book full of people who can’t be pinned down to one place”.

The book opens in Kerala and recounts the first meeting of Ammu and George (Thayil’s parents). Thayil was preordained to move from city to city because his parents were peripatetic. His father’s work as a journalist and editor took the family from Kerala to Bombay to Bihar to Hong Kong to Bangalore. His mother emerged as a fearless go-getter as adept at the stock markets as she was as a swimmer in the backwaters of Kerala. The book is dedicated to Ammu George (1934-2025) “who preferred the fictional over the real”. Her life provides the start and end of the book. She died on January 2, 2025, and this book uses the grief of her passing to celebrate her life.

While using original photographs of his parents and other protagonists in the book, Thayil chaffed against making this book entirely nonfiction. Speaking from his parents’ home in Bengaluru (which he moved to in 2018 to be “a son and not the black sheep”), he says he chose to call it a documentary novel, “because so much of it is documented and documentarial—if that’s the word—and there are a lot of real places, names, characters, organisations, journals, events, historical events, a lot of that is real. But the thing that ties it all together is fiction, is the imagination”.

Sixty-five-year-old Thayil says he had to complete the Bombay trilogy to arrive at Kerala. He has long been “hoarding” his Kerala material and needed to find the correct medium for it. The nonfiction novel proved to be the apt vehicle. He says, “For this book the longest time was taken in just trying to find the right kind of format for it, because it’s a form I’d never done before, it took a lot of trial and error until I finally found the right way to do it.”

If Thayil’s wanderings started in his childhood, his interest in literature was similarly seeded then. In The Elsewhereans we learn of how his father and uncle both harboured literary dreams. His father who authored 20 nonfiction books always wished to write a novel. His uncle was a lawyer who always wanted to be a poet. By chance, Thayil took on both roles. Thayil was first educated at George’s library. Here he read James Joyces’ Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. Here he chanced upon a first edition of Dylan Thomas’ poetry which he still has. George pored over these books not only for pleasure, but also for study. He hoped to one day write like them. Similarly, Thayil’s uncle had an “unhealthy obsession” with Baudelaire. He led a 14-year-old Jeet to the French poet, essayist, translator and art critic, as his home in Kerala was “actually a library/ shrine to Baudelaire” as it had every book by him in French and English. Speaking of these Malayali men of thwarted dreams, Thayil says, “Something of that transferred to me by osmosis. And so with these two writers, in my family, I felt I had kind of a duty. And it was a pleasure to tell their stories in an interesting way, in an entertaining way.”

Thayil mentions in the book that George was the “kind of writer who can’t start a sentence with the first-person pronoun”. I ask if he is afflicted with the same condition and if fiction provides an exit route. He says that parts of the book were written in first person and he then changed it to third person, which freed him in many ways. He adds, “The minute you make it the third person, everything changes. You bring in all kinds of things that you probably would not have brought in when it was first person. You allow your imagination to run riot. You can turn yourself into a loathsome character.”

George emerges in the book as a difficult character, a father who wouldn’t talk, a husband who is absent. Through the course of the book he also changes, diminishing with age. As Thayil writes towards the end, “Because of his failing memory and lack of hearing, he becomes genial, very different from the humourless authoritarian I’ve known for most of my youth. He’s forgotten how to be a bully.” Thayil says it has been difficult to write about him as there are parts that are absolutely factual and those which didn’t happen at all. The son says, George has been reading the book in which he sees himself do things he has done, and hasn’t done, and “he’s been very wise and calm and mature in the way he’s handling that experience.”

For nearly a decade, when he was deep in his Bombay trilogy, Thayil had said he would not write poetry again. While he has continued to edit and anthologise, the last two years have seen the publication of two significant collections of poetry; I’ll Have it Here (2024) and The City under the City with John Kinsella (2025). Thayil says initially he would do 70-80 drafts of a poem. But on a recent commission he spent a few hours over a poem and was pleased with the result. He says, “It was such a pleasure to do. Maybe coming back to poetry after such a long interruption freed me in some ways. I just didn’t feel that anxiety of influence and all those dead poets staring over my shoulder at my screen and shaking their heads with disappointment and frustration.”

While writing fiction he doesn’t deal with the same anxiety, as fiction just takes on a life of its own, which shushes disapproving literary ghosts. The writing of The City under the City bled into The Elsewhereans, as the latter was originally much longer. But he found that an entire chapter often worked better as a six-seven stanza poem, and in this way both forms have nurtured each other.

The city has been the one common thread in all of Thayil’s work. It is unsurprising as he has never lived in a single place for more than five to six years at a stretch. Given both his appearance and demeanour he is often mistaken for a resident in different parts of the world, whether it is Warsaw or London or Hanoi. He says, “I’m totally from Elsewhere first. I’m very comfortable in between places. I’m never just a tourist. I am very comfortable in the margins. And in the places where migrants and that shadowy race of traveller lives.” It is in these margins that we the Elsewhereans find home.