The Art of Repair

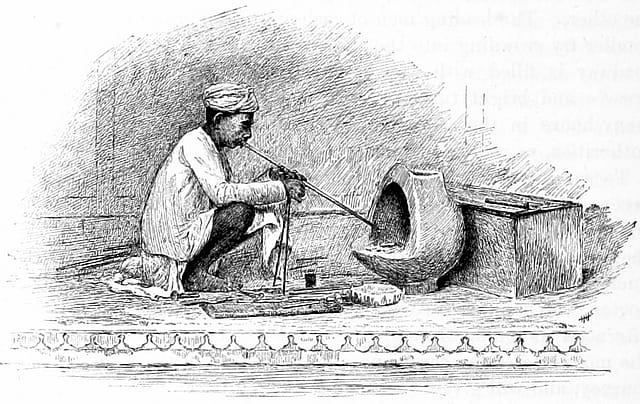

In Anukrti Upadhyay’s Kintsugi, we first meet Haruko, a Japanese-American with Korean roots, who arrives in Jaipur to learn the art and craft of jewellery-making first hand from the famed goldsmiths of the city. An unfortunate accident takes her away from the traditional workshops abutting the famed jewellery market of the city, threatening to derail her apprenticeship. But one of her mentors, an acclaimed and talented goldsmith, invites her to his own house to recuperate. His family members are only too happy to look after their unexpected guest, especially Leela, the youngest daughter of the house. The sunar sets up a table for Haruko so that she can continue her training and she is delighted. For Haruko, jewellery making is more than a profession, it is a craft, an art and a precise science all rolled into one. When Haruko enthusiastically speaks about jewellery making, she inspires Leela to take a closer look at her father’s work.

Leela sees first hand, Haruko’s diligence to her work and the deep satisfaction that comes with coaxing precious metals and stones to form intricate pieces of jewellery. Leela also observes the quiet way in which Haruko turns her life around in the face of obstacles that threaten to crack the contours of her life. In a patriarchal society, the concept of a woman working as a sunar or goldsmith is unheard of, yet Haruko’s brief appearance in her life gives Leela the courage to break open the door to this forbidden space when her father falls ill, even when the people of her community frown in disapproval.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Upadhyay has used the Japanese concept of Kintsugi, as the title and theme for her book that looks at the lives of six people whose paths intersect in spaces and situations spanning continents. While we meet Haruko, Leela and Prakash in Jaipur, Meena, Yuri and Hajime are presented to us in Japan. Ever present at the heart of the narrative is an echo of loneliness, loss, longing, and unfulfilled promises.

Kintsugi or the practise of mending a broken object with gold to restore the object may not bring back the original utility of the object. But what it does is create another use for the object or simply convert it into a thing of beauty to admire. While looking at Haruko’s design books, Leela chances upon a broken bowl repaired with gold fillings and she is shocked at seeming wastefulness of it, ‘…Can it (the repaired bowl) hold water?’ she asks Haruko who replies, ‘Not all vessels are meant to hold water, some are meant for allowing water to seep away.’

When Haruko appears again, in Hajime’s story, she is an acclaimed jewellery designer whose designs are much sought after. A successful professional with an elegant personality, her quiet confidence is apparent now as she navigates personal and professional relationships with aplomb. Meena, a literature student in Japan, does not know how to tell her family back home about her girlfriend, while Prakash decides it is safer to go along with his family’s plan rather than listen to his heart. When Hajime’s life veers off the path suddenly, he is at a crossroads while Yuri’s tragic abandonment in childhood seems to have followed her into adulthood too. Leela, inspired by Haruko, fearlessly forges a path for herself amidst the disturbances of her life, but Meena, Prakash, and Hajime flounder and Yuri finds it quite difficult to gather together the broken pieces of her life.

Upadhyay’s descriptions of places are immersive, whether the bustle and heat of the bylanes of the jewellery market in Jaipur or the cool mountain towns and ordered neighbourhoods in Japan. The description of the scents and sounds of the locations add to the reading experience. Upadhyay writes in detail about the elaborate process of fitting together diverse elements in various forms of jewellery making—kundan, meenakari, thewa, which forms the perfect frame for fitting together the narratives about each of the characters.

When Leela says to Prakash, ‘If there is a flaw in the first moulding, however much you patch it up, the ornament will remain imbalanced. The only solution is to start over again, even though precious metal is lost in the process,’ she is referring as much to jewellery making as also to the choices taken by him.

In Kintsugi, the author shows the extraordinary strength inherent in the lives of ordinary people if only they had the courage to tap into it without fear.