Pankaj Mishra’s Protest

THE LIST IS impressive. In a span of 200-odd pages, Pankaj Mishra has taken potshots at the who’s who of the intellectual world and beyond. Historian Niall Ferguson, The Economist, the late Milton Friedman, India’s ‘military occupation’ of Kashmir, Islamophobia and, his new fascination, the failure of Western Liberalism.

After reading the book one doesn’t know what survives. Indian capitalism cohabits with social Darwinism in Mumbai; Brexiteers have made a colossal error that Britain will pay for dearly; Western Liberalism—and its historians—has successfully hidden its bloodsoaked history; and other woeful tales abound in the book. Liberalism can be salvaged but the ‘how’ of doing that eludes Mishra.

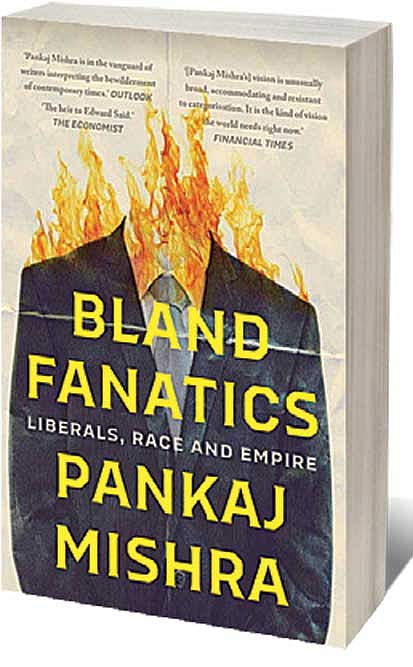

What can one say except that Bland Fanatics: Liberals, Race and Empire is a book of angry essays that leaves one dazed.

At one time, not adhering to a set of ideas, ideology or outlook was considered a mark of intellectual purity. Mishra belongs to that school. That was also the time when intellectuals were arbiters of good taste, the bounds of human possibilities and, in some cases, even moral acceptability. It was also a much simpler world. In the years between 1950 and 1991, only two rival ideologies had any real space: Communism and Capitalism. To be sure, there were forms of Third-Worldism—Nehruvian Socialism, African variants and assorted ideologies—but these never had much space on the world canvas. With 1991, the field became constricted to the point that only one ‘ism’ survived: Capitalism. To that was grafted a very different ideology: Liberalism. For all the ideological baggage tied to Capitalism, it was first and foremost a system of decentralised production, distribution and consumption. Liberalism, on the other hand, was more an idea up in the air until that point. It had a historical lineage that went back to Benjamin Constant (1767-1830) and even further to John Locke (1632-1704). There was a parallel American version dating to James Madison (1751-1836). But right until the end of the Cold War, no one thought it would become a governing principle with its own manual of acceptable and unacceptable practices. By the end of the first decade of the 21st century, Liberalism, too, was in trouble. This was waiting to happen as the ideology had acquired the trappings of a bastardised theology. But unlike an original theology, it lacked a spiritual core, something that did not escape the sight of people-at-large.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Might Mshra’s idea of freewheeling protest become relevant in the age of Nationalism? One can’t say anything about the future but for the present, this is unlikely. On the one hand, the force of nationalism is now beyond intellectual questioning. On the other hand, the world is yet to acquire a system of production that supersedes Capitalism. Notwithstanding the rising barriers to trade and the sway of protectionism, markets remain essential. In practical terms, whatever ‘isms’ are dreamt up, they have to function between these two poles. To borrow an idea from economics, Mishra is facing a ‘reverse Tinbergen problem’. The Tinbergen Rule—named after the Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen—states that policymakers must have one policy tool for every policy target they have to achieve. Mishra has too many tools at hand and too few targets to achieve. Capitalism and Nationalism are sufficient for the task of ordering the world.

Intellectual protests shorn of some link with reality become sterile after a while. They don’t die but remain in some rarefied world that remains inaccessible to ordinary people. One fears the same fate may befall Mishra’s ideas even if they are eloquently argued. No country and people escape his piercing gaze. Unfortunately, this is the world one must work with even if one is trying to make Utopia. Alas, the world is content with much less.