Nehru: The Idealist and the Realist

WHEN JAWAHARLAL NEHRU died in 1964 he bequeathed a by and large peaceful India to his successors. To be sure, there were problems. Pacification efforts in Nagaland failed and five years earlier it had become necessary to impose a draconian law giving unusual powers to the armed forces. Two years earlier, China had beaten India in a short but intense war. Nehru never recovered from that blow. But overall, India was on the right track. States had been reorganised successfully; a system of economic planning was created and at a time when democracy was failing in newly independent countries, India stood out as a successful example.

Fast forward to the end of the 20th century and virtually all ailments that plagued India were blamed on Nehru. His strategy towards China was held to be the root problem for India’s territorial losses in the Himalayas. The “appeasement” of Muslims by his party was traced back to the choices he made

after Independence. The interesting thing is that with the same set of facts, he has been criticised by Leftist and conservative intellectuals alike. One British Marxist intellectual went so far as to discern a reactionary Hindu in him. For conservative Hindu intellectuals, he was not Hindu enough. Only the Liberals, the dominant intellectual tribe in India, think he was right all along.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The best way to understand Nehru, the context in which his ideas emerged and debates of the time, is to wade through his selected works and the speeches, letters and writings of those who raged against him. But that literature poses great difficulties for the ordinary reader. The Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru are spread across a hundred volumes. Responses to his writings by others are equally scattered. Of late, efforts are being made to collect these texts in a thematic fashion to make life easy for readers.

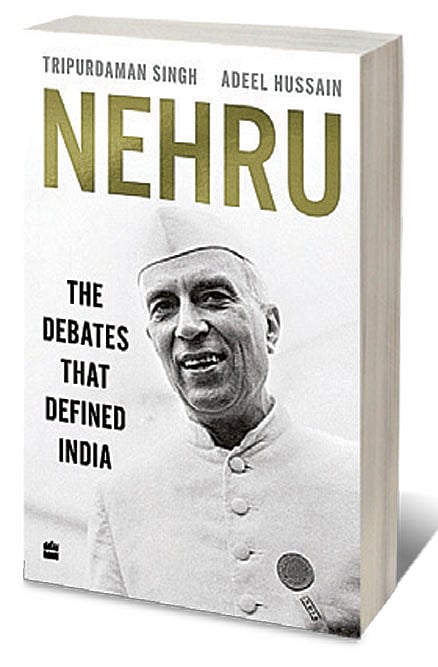

Nehru: The Debates That Defined India by Tripurdaman Singh and Adeel Hussain is one such effort. The book extracts key documents and writings that deal with four very different themes that continue to dominate debates in India until now. Thematically, there are three debates. First, broadly speaking, the “Muslim Question” of the pre-Independence era involves Nehru’s exchanges with Muhammad Iqbal—the Muslim theologian and a key intellectual figure of Muslim separatism in 20th century India—and those with Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Second, the debate between Nehru and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel on foreign policy and in particular China and, finally, the debate around the First Amendment to the Constitution that had far-reaching effects for the Indian polity.

What arises from these debates is a complex figure who—after all the twists and turns—emerges as a territorial nationalist first before anything else. If one were to sketch a line from the liberal-idealist to the realist-nationalist end, the debate around the “Muslim Question” is the one that lies at the liberal end. The First Amendment issue, one that liberals would like to somehow vanish, is firmly located at the realist end. The debate on foreign policy can, with many complicating qualifications, be located more towards the realist than idealistic end.

Consider the “Muslim Question” and here Nehru seems to have been outwitted by both Iqbal and Jinnah; the former on theological grounds and the latter on political ones.

Unlike Nehru, Iqbal had no illusions about what his religion stood for and what he—as a conservative leader—wanted. To be sure, Iqbal had his own complicated conception of what Indian nationhood would entail but he did not want a “forced unity” of communities. This was expressed in a far sharper manner by Jinnah for whom the price for Indian unity would be a decentralised state where individual units would call the shots. Nehru’s weakness, if it can be called that, was a poor comparative understanding of religions. What emerges from these debates is an unvarnished relativism of sorts where all religions can be equally prepared for entering modernity. The contrasting fates of India and Pakistan—a fascinating natural experiment—shows how erroneous his assumption was. Iqbal and Jinnah were very clear about what they wanted and they managed to get it. For all the rap that Nehru received about his “woolly idealism”, it is the creation of Iqbal and Jinnah that is in trouble and is yet to resolve its identity issues.

At the other end of the spectrum lies the debate around the First Amendment to the Constitution that imposed “reasonable restrictions” on the Fundamental Right to Freedom (Article 19). The book covers one aspect of that debate, between Nehru and Syama Prasad Mukherjee. A fuller treatment of the debate is in a book by one of the authors (Singh’s Sixteen Stormy Days: The Story of the First Amendment of the Constitution of India, 2020).

At that time this was held to be a regression from the promise that had been given just a year earlier when the Constitution was ushered in. Nehru was criticised for harbouring some deep anti-democratic tendencies. But 70 years later, that amendment has stood the test of time and has helped India survive as a nearly coherent nation-state. The authors may disagree, but that amendment surely ranks as one of Nehru’s great contributions to the survival of India. At that time, there was no internet, no WhatsApp, no social media and none of the disruptive technologies that made it easy to gang up against the government. And yet, within a year of the Constitution’s arrival, Nehru probably sensed—and rightly so—the perilous road ahead.

The Nehru who emerges from these debates is not a wooly liberal, but someone who with his education was an idealist and a realist in different proportions. The trouble in understanding him lies in our quest for neat, clear-cut, classificatory pigeonholes and the way we want to push leaders and individuals into them. It is also easy to blame him for the “mistakes” that continue to haunt India. Take China, for example. A careful reading of the record shows that he was a territorial nationalist through and through. Where he made an error was in appreciating Chinese intentions and strength. Similarly—on a topic that is not covered in the book—he was very clear on Kashmir.

The trouble for him, and India, was that it was one matter for a world empire to hold a territory and something entirely different for an independent country to do so. The resources required—material, ideological, legitimising—were of a very different order. Perhaps what was needed and what India possessed were badly mismatched. Yet, to the chagrin of the Chinese and Pakistanis alike, he did not let go of India’s territorial claims. One well-known commentator on international affairs has for decades blamed Nehru for not demarcating the border with China and artificially sketching a line in Aksai Chin. It is interesting to note that there has been no comment from that quarter about China’s “Nine-Dash line” that claims the entire South China Sea as its territory. It is always easy and cheap to blame the dead. There is no doubt that mistakes emerged as he went along but to blame him totally (or absolve him, for that matter) tends to impart an otherworldly, non-human quality on him.

It is high time that India and Indians stopped criticising Nehru for his personal failings and mistakes and analyse the context in which he made the choices that he did. Singh and Hussain’s book is a good starting point to examine the basis of those choices.