‘Mindwandering Is Where Creative Thinking Happens’

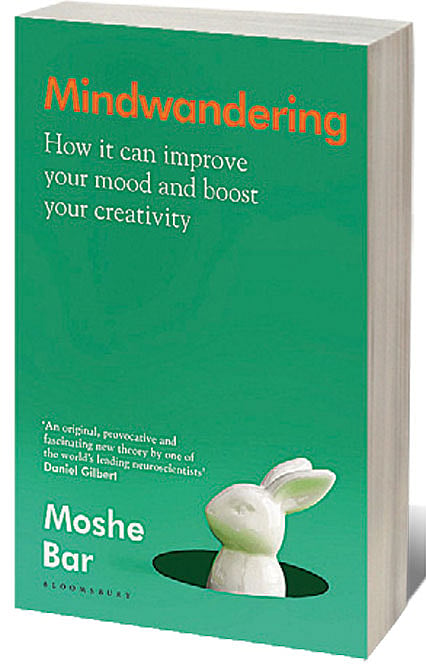

ISRAELI COGNITIVE neuroscientist Moshe Bar’s book, Mindwandering: How It Can Improve Your Mood and Boost Your Creativity (Bloomsbury; 272 pages; ₹ 599), couldn’t have been released at a more propitious time. There is a certain doomsdayness to the world in its present state. We’re slowly emerging from the pandemic into a world where some countries are at war and a climate crisis that is only worsening. Our minds go wandering along different alleys of thought, perhaps more so now than before; we can’t stop our minds from buzzing with all kinds of concerns and scenarios, even if we tried. And here is Bar championing mindwandering (with certain caveats, of course).

In his book, he examines the phenomenon of mindwandering and what is actually going on in our never-resting brains when it happens, and proposes its varied benefits when circumstanced rightly. Over a Zoom interview, Bar speaks about mindwandering’s link with creativity and contentment, how mindwandering and associative, broad thinking could potentially help with depression, and who his book is meant for. Excerpts from an interview.

What is mindwandering, and how is it different from daydreaming? Mindwandering generally has a negative connotation, but daydreaming seems somewhat permissible. How are these two different?

One of my missions with this book is to rid people of the guilt of mindwandering that society has kind of programmed us to feel. I wanted to highlight the positive aspects of mindwandering, so that people feel liberated and encouraged to engage with it. Mindwandering is a collection of processes, and one of them is daydreaming. Other processes include when you’re deep in thoughts about the future, or reminiscing about the past, or simulating possible scenarios and possible futures. And, of course, creative incubation. When you require creative thinking, mindwandering is where it happens.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

According to the book, the default mode network or the DMN is where mindwandering operations take place. What is the DMN and why is it important?

For many years, neuroscientists thought that when we tell participants in our experiments to rest between conditions, their brain really goes to rest. But when we looked at their brain using functional MRI and examined what was happening during this rest period, we realised that the brain is actually very active when we’re not doing anything, when we’re not engaged in a specific task.

The default mode network is a massive network of big cortical regions that are connected and active when we’re resting. By default, our brains are very active. Half of our waking hours are dedicated to mindwandering. We’ve understood by the logic of evolution that there must be a reason for why nature has spent so much time and energy on activating such a global set of brain areas. The DMN is the platform and the vehicle for our mindwandering.

The scope of mindwandering is wide, and it doesn’t distinguish between the various aspects of our lives—personal, professional, social, and so on. How can one harness the benefits of mindwandering in these different aspects?

It is indeed the case that mindwandering has a mind of its own, so to speak. It’s a beast that is not going to be tamed. We cannot really tell ourselves to start or stop wandering.

One can harness it, first, by raising awareness. This sounds like a cliche, but it works very well. Realise that mindwandering can be good, that it happens by default, and that it can help creative thinking and innovation, and enable a better mood. Secondly, when you’re in the streak of mindwandering, give it a chance to develop and see how it unfolds. This could be a good place for caveats because there’s also mindwandering that’s not good for us: obsessive thoughts, ruminations, worries can all be unhelpful. The question is, can we learn to distinguish and encourage one but not the other?

When you talk about associative thinking, you say that one should “think broader to feel better”. Can you expand on that?

We discovered that there is a reciprocal connection between mood and creative thinking. Creative thinking is usually associated with broad associations. What are broad associations? If I ask you to give me your first association with the word, ‘table’ and you say, ‘chair’, that would be the nearest association. It’s the most obvious and the most frequent one. It’s very correct, but it’s not creative. If I say ‘table’ and you say ‘wood’ or ‘tree’, then in this case you went further on. It indicates that you’re thinking in a broader, more original manner.

We found that a positive mood is associated with broader associations, higher creativity, and broader mindwandering. What’s interesting is that we can also do the opposite. And not only in the lab. We have a start-up company that tries to treat depression and improve mood by making people think more broadly. To improve mood we show a list of words, or engage in other methods to make the scope of thoughts more associative and broader. We can take advantage of these techniques. When you want to feel better, you could try playing with creative thinking. When you want more creative thinking, you should look at how to improve your mood.

You talk about two states of mind, exploratory and exploitatory. The first one is when you’re looking to be creative, and the second one is when you try to focus on a narrow, familiar area. How long do you think these states of mind last? Do they fizzle out or fade away, or do we require a trigger or a distraction to enable a shift in state?

By and large, there is no limit to how long a state can last. They are dynamic and affected by contextual factors, such as the people around you, where you are, whether you’re in a new or familiar environment. Changes to your state of mind can be gradual. If you’re in a good mood, sitting in your living room and reading a sad story, then your mood will gradually change from good to bad. If I land in Varanasi in an exploitatory state of mind, and see all the amazing and exotic things, I would change to being exploratory instead of exploitatory as I approach the novel and the uncertain.

But there is a different time course to these different processes. Attention, perception, thinking, openness to experience and mood are all tied together. But if you change one parameter and it happens to change quickly, it may not be so for the others, even if everything will align after a few minutes. Attention can change very quickly from the ‘forest’ to the ‘trees’—from the global to the local—but mood will follow suit a little slower. Overall, in terms of how long a state can last, I would say anywhere between seconds to hours, but not more than that.

An overarching sense I got from your book is that when we’re working with the human mind, we’re treading on contradictions. This perhaps explains the multidisciplinary approach you’ve taken, where you’ve welded together cognitive psychology, neuroscience, spirituality, philosophy and other disciplines. How do we arrive at a balance amid these contradictions?

It’s not so much a contradiction as it is a conflict between two opposing forces. One wants to excite, the other wants to inhibit. One wants to minimise uncertainty, the other wants to maximise learning. So the balance you talk about is really the state of mind we have, and it differs depending on the situation. When you’re visiting a foreign city that is very different from what you know, your balance will be closer to exploring. When you’re in a dangerous environment and you want to be protected, then your balance will be somewhere else. These forces are always there. The balance between them, and where this balancing point is, depends on the context.

What are the changes that you’ve brought about in your life and in your family’s life, based on the research that you’ve been doing on mindwandering?

There’s a lot of it. First of all, my kids know that if I haven’t listened (and I’m very often not listening), it’s not because of them. It’s because I’m deep in a wandering of thoughts. This holds true for all of us. So, we exercise better patience and are not offended when somebody asks us to repeat because they’ve been lost in thoughts. Also, when I see my kids lying on the sofa and staring at the ceiling, I’m very happy about it and walk on my tippy toes so as not to disrupt them in their wandering because I know it’s usually a platform for good things to happen. Even when it comes to memory, we are aware that there are all kinds of distortions to it, so we know to take our own memory with a grain of salt. Other people might take memory as truth and as facts, but we realise that it’s fallible.

While you were working on this book, who did you visualise would be your audience, and what is it that you hope they gain from your book?

I noticed that while I was writing the book, depending on where I was and what my state of mind was, I saw different kinds of audience in my mind’s eye. My audience could be someone who wasn’t highly educated but nonetheless curious and liked to learn. Or it could be someone who has already read all the popular science books about the brain, for whom I’d really have to work hard to offer something new. The book itself is also diverse. There are sections and chapters that are easily digestible by someone who is less informed, and others that could be challenging for those who have read similar things in the past. In terms of what I’d like to achieve through the book, I have to tell you, it’s a great privilege to put my thoughts in writing and to say that people are interested in reading it. But my biggest hope is to make the science and the amazing findings, not just mine but from all of my community, available to all our fellow humans. If they can implement that knowledge in their daily lives in a way that makes them happier, then it would be a real privilege for me—to know that our research actually helped people.