Madness of Mountains

On New Year’s eve of 1932, Maurice Wilson made a resolution. The Englishman wanted to climb Mt. Everest the following year, after flying a plane to the base of the mountain from the Stag Lane airfield in north London. If that sounded bizarre, the circumstances surrounding it would make this plan sound downright absurd.

For starters, Wilson knew nothing about flying a plane. And until then, he had never climbed a mountain in his life. Yet, a year later and against all odds, Wilson was on Everest, having flown solo in a Gipsy Moth biplane as far as India.

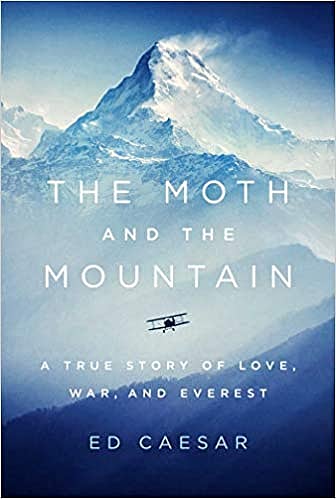

In The Moth and The Mountain, Ed Caesar relives this enthralling journey that makes up the final chapter of the outlandish life of Wilson.

After enjoying a privileged upbringing, Wilson decided to serve his country during the First World War. Though he survived brutal combat on the Western Front, followed by the Spanish flu of 1918, the mental scars were evident as he returned to England as part of a broken generation, trying to rediscover its place in society.

When the British sent their first lavishly funded expedition to Everest in 1921, Wilson was fighting for mere sustenance. In the years that followed, he travelled to lands as far as New Zealand and South Africa, trying his hand at everything from running a business to dealing with failed relationships. The ennui was deep-set, his health failing him time and again, but each time, he set it all aside to bounce back and continue his search for meaning to life.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

By 1932, Wilson had had his brush with Buddhist mysticism, abstinence practiced by Indian yogis and was in awe of the monkish aura of folks like Mahatma Gandhi. The search for purpose and enlightenment was a constant. That moment arrived while convalescing in Freiburg when he read about the last British expedition to Everest in 1924. The disappearance of two climbers, George Mallory and Sandy Irvine, had made big news and they were deemed national heroes. Wilson had now found something to drive him each day.

He started dreaming Everest. He climbed his first mountain, he took his first flight. He invested in expensive gear and experimented with fasting. Everything he did that moment on was one step closer to climbing the highest mountain in the world. He even found a believer and a soulmate in Enid Evans, with whom he hoped to be with some day. The announcement of another British expedition to Everest in 1933 teased him; he now wanted to beat them to it.

A parachute jump almost set his plans awry, even alerting British authorities in India of his impending travels. They gave him every reason on why he wasn’t welcome. But by this time, Wilson was only listening to the little voice inside his head.

On a Sunday morning in May 1933, he jumped into his aircraft christened Ever-Wrest. It’s the moment he had been dreaming of, when the spotlight would firmly be on him. He felt invincible, optimistic and now eager to get his monumental journey underway after weeks of planning.

He was soon hopping cities while flying east of England, stopping for lunches and turning in for the night as if on a road trip. The complications along the way were aplenty and his mission seemed in jeopardy time and again, especially after his plane was impounded in India. But these were but a few delays that he embraced wholeheartedly. There was no question of turning back. Under the cover of night, he set off from Darjeeling on foot, eventually hopping across the border into Tibet alongside his Bhutia companions, until he finally stood at the base of Everest.

In hindsight, Wilson was never really equipped to tackle the challenges posed by a mountain of this magnitude, despite his lack of fear and willingness to endure. Yet, how Everest toyed with the minds of romantics like him makes his attempt an integral part of the peak’s eternal history.

Caesar has made a hearty effort to decipher the mind and stitch together the life of a man about whom little has been recorded. It’s a fascinating account for anyone with a little bit of madness, just like Wilson.