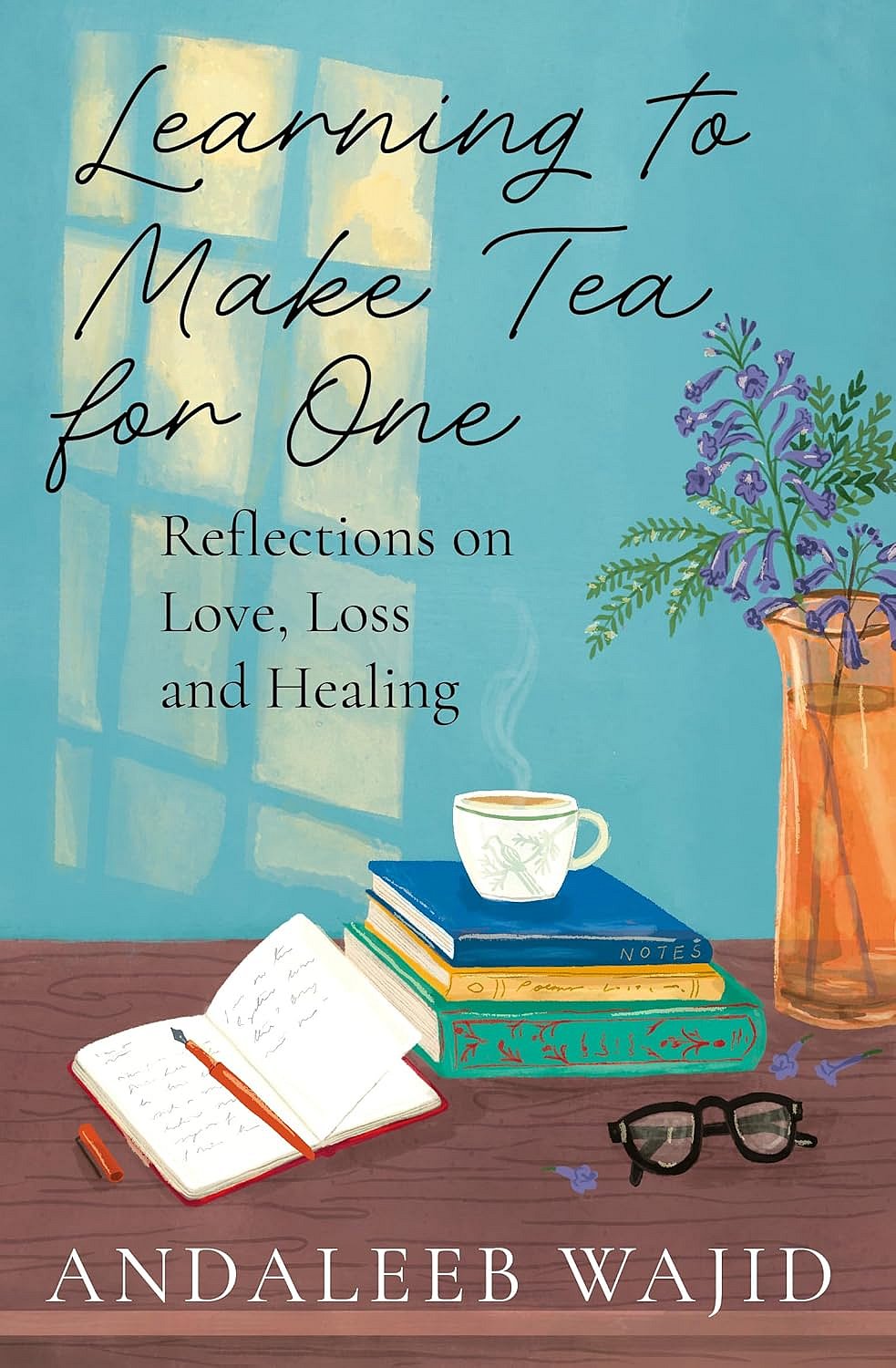

Journey through Grief

Andaleeb Wajid’s Learning to Make Tea for One is a memoir documenting her ebb and surge of emotions as she copes with the illness and eventual passing away of her mother-in-law (who was also her aunt), followed by her husband, during the Covid-19 pandemic within a span of five days in the summer of 2021. In untangling the threads of her grief, the author ends up celebrating her love for them, particularly her husband Mansoor.

She was 19 and still in college when she got married to her cousin who was in his late twenties. They spent 24 beautiful years together, which involved bonding over their love of “trashy songs”, cooking biryani, raising two beloved sons, and getting on each other’s nerves. The author does not force herself to make it seem that everything was picture perfect, but she does depict how they both made sincere efforts to accommodate and nurture each other.

She used to make tea for him whenever he demanded it though she did not like either the taste or the aroma of tea. He accompanied her to many literature festivals though he was not much of a reader. In fact, he had not read even a single book written by her. She recalls, “He was there with me, and he was happy to see me shine. For someone who was rather egoistic, this was a sign of love that I didn’t recognize until quite late in our shared life.”

By revealing intimate details about him throughout the book, she makes him come alive for the reader as a man who was a caring husband, a doting father, an indulgent son, and a person filled with zest for life. She does this not only for her own sake but also to rescue him from the dehumanising experience of being reduced to a patient by the medical-industrial complex.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Wajid’s mother-in-law too has an important place in her heart and in the book, and so do many other members of her family who did their best to be there for her during the tragedy.

Reading this book is like applying a soothing ointment to heal a wound that is in no hurry to disappear. It does not provide instant relief, but it fulfils the promise of comfort. Though Wajid makes no attempt to hide her pain, she refuses to perform for those who expect her to “look hollow-eyed and sad”. She writes, “…in my head, I don’t feel like a widow…I still feel married to Mansoor, just that he’s not here. So why should I dress or behave differently?”

The author does not claim to speak for anyone other than herself, but it is not difficult to imagine how her words would offer courage to women who are made to feel that their personhood and their place in the universe is diminished by the absence of their husband.

In articulating her own reality with clarity and confidence, Wajid acknowledges the right of every person to grieve in a way that seems right for them. “If there’s one thing my loss has taught me, it’s to stop being judgmental of people and how they handle their grief,” she adds, emphasising how unhelpful it is to be told that one needs to “be strong” for one’s children.

She shows how such remarks from supposedly well-meaning visitors can hurt instead of lending support at a vulnerable moment. Explaining her irritation, she notes, “…while my children mean the world to me, this implies I have no existence of my own outside them.” She also calls out the unfairness of a patriarchal society that expects widowers to marry as soon as possible after their wife’s death, whereas widows are defined by their role as mothers.

This book is not only for people who are grieving. It is for everyone, because the agony of losing loved ones to death is universal.