‘I tried to think of a way to put the human back into a world history,’ says Simon Sebag Montefiore

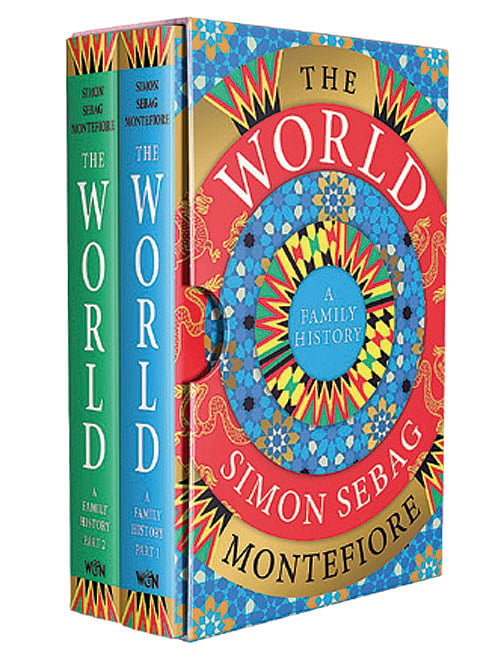

LONDON-BASED HISTORIAN Simon Sebag Montefiore, 57, has written compelling biographies of Catherine the Great, Joseph Stalin, Russia’s Romanov dynasty and the city of Jerusalem. The multiple-award-winning former journalist is also a television presenter and author of many novels. He has been translated into 48 languages. Montefiore now returns with The World: A Family History (Hachette; 1,344 pages, ₹1,899). The tome in two volumes maps the story of humanity through families. It’s a wide-ranging and spirited account that unfolds across geographies, narrating world events via the Caesars, Incas, Ottomans, Mughals, Bonapartes, Habsburgs, Zulus, Rothschilds, Rockefellers, Churchills, Kennedys, Castros, Nehrus, Pahlavis and Kenyattas, among others. It’s a mix of well-known figures from the past as well as lesser-known names including Hongwu, the founder of the Ming dynasty, Hawaiian conqueror Kamehameha and Moroccan pirate-queen Sayyida al-Hurra. During a Zoom interview, Montefiore speaks about history writing, Putin, why this book almost killed him, and more. Excerpts:

How did this book come about and why did you frame it in terms of families?

As a historian, I’ve always wanted to write this book. I happened to be about to start it when the lockdown happened. I actually started writing it on the first day of lockdown in 2020. That was brilliant, because I needed focus. People have asked me to do a world history, after I did the Romanovs book, and the Jerusalem book. I felt that so often in world histories the human element is missing. You get lots of lists of commodities and technological improvements and industrial developments. And you don’t get the human element, the idea that there are really people involved in this. And even in books that I really admire, like those by Jared Diamond and Yuval Harari, I got that impression. So I tried to think of a way to put the human back into a world history. And I came up with this very simple idea that families are the essential unit of human life from the beginning, and even now in the 21st century. So the idea is simple: to combine the span of world history with the juice, the grit of human biography.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

When you do something with such a vast scope, is it daunting at the outset? What were some of the challenges?

It’s incredibly daunting. Writing this book almost killed me. There were times when it was really a struggle. I just couldn’t sleep, I was thinking all the time of stuff I needed to do, work I needed to master. The essence of writing the book is that you have to master a lot of subjects. And mastering them means deciding on an outlook. But then you also have the narrative challenges, how to link everything together. You don’t want to write a book that’s just a series of separate chapters. Everyone’s done that already, many times. The whole point about this book is that it’s a single narrative. From the Stone Age to the Drone Age, if you like. So that was a great struggle. And of course, the great questions are what to put in, what to cover and what to leave out. And when you’re doing a family history, obviously you have to make big decisions about families, which to include and why. Oftentimes, there are great dynasties like the Medici or the Habsburgs where they dovetail perfectly with great artists that I wanted to include anyway. Or for example, the Bavarian king Ludwig the Mad, he dovetails perfectly with Wagner. There are lots of examples where you can see why I included some people and not others. Some of them just selected themselves. For example, in India, the Mughals or the Nehru-Gandhi family, were obvious ones. Because the Nehru-Gandhi family is a way of telling the story of the first 60 years or so of the world’s greatest democracy.

Which were some major families that got left out?

I missed out the Thai royal family and the Thai kingdom. I wanted to put much more about Thailand but I chose instead to include Cambodia, that was a trade-off. I chose to cover Albania instead of Croatia, for example. I was more interested in Romania. I know Romania better than I know Bulgaria.

This is a work of synthesis, as you say, but much of your previous work has been archival. Which is more enjoyable?

Well, I love archival work. And I think every historian you speak to will tell you that archival work is the most exciting, because you’re actually holding papers, written by Catherine the Great or Stalin. So, nothing beats archival work. But this is a book I always fantasised about writing, because I was never interested in just reading about the Tudors in Britain. I was always a bit bored by that. I always wanted to write about India, about Tibet, about China, about Africa. And I’ve always been reading world history. So, in many ways, this is my dream book. And I think this is the book that I’m most proud of in my career.

What interests you about power or looking at power that flows through families particularly?

I’ve described myself as a historian of power. And that’s why many of the families in the book are what I call power families. Some of them are in democracies, like the Nehru-Gandhis, but some of them are essentially, autocratic monarchies, like the Kims of North Korea or the Assads in Syria. I’ve always been fascinated by how power works. I studied it at university. All my books have been about that in some form or other. Family is a different thing. Family takes it a step further, because family allows you to give continuity, to have a feeling of human life developing. And, of course, that’s the attraction also, of families as political institutions. Power families seem to be a mirror of ordinary families. And yet, they’re different. They offer continuity, reassurance, stability. In fact, most kinds of political institutions are trying to achieve those things too, trying to achieve stability in a turbulent world. That’s why I think that family rule has been the predominant ruling institution in the whole of human history.

We have power families in India, and globally too. So, what is the inherent attraction of having ruling families even in a democratic system? How does that happen?

It’s very attractive because you have this aura of reassurance, stability, continuity, which are very attractive features. They are really the things that we seek in all political systems, and all political systems are designed to achieve those things that are quite hard to achieve in a wild, crazy world. And the great thing about what I call ‘demo dynasties’, in other words, dynasties in democracies, is that you get all the advantage of the experience of their advisors, someone who’s brought up understanding how power works, but you can get rid of them too. And that’s the great thing about the democratic system. It’s inconsistent; you can elect very inexperienced people, you can elect the wrong people, but you can get rid of them too, either at the ballot box, or in the workings of the democratic system, as we’ve been seeing in England recently.

But you did not write about the British Royal Family, why not?

Because I’m a student of power, and they don’t have any power. I didn’t write about any of the constitutional monarchies: Sweden, Belgium, Luxembourg, or Britain. I didn’t write about the British Royal Family, because their importance is symbolic. In this book, I’m more interested in the Kim Dynasty of North Korea than I am in the Windsors.

What do you make of the Harry and Meghan documentary?

Very little. I think it’s very boring and very unexciting. It’s totally unrevelatory, extremely portentous and self-indulgent, without really being at all momentous. I think it will change nothing. Like much of reality television of which it is a part, it will be quickly forgotten, and people will move on.

When you look at so many families across time and place, what were some of the commonalities, or were they very different?

They’re as dissimilar as political systems are dissimilar, in the sense that political families are very flexible, and quick to adapt. A family can be regarded as and promote themselves as a sacred monarchy, and a century later, they’re promoting themselves as representing nationalism, which is a completely different idea. And then they can become parts of the democratic system as all the constitutional monarchies have. So they’re very flexible. But what they have in common is there are always tensions within all families. This is why Samuel Johnson said, ‘Every family is like a little kingdom, and every little kingdom is like a little family’. Because there are tensions built in. The whole idea of political families is to provide stability. But it’s a balance. Within that institution, there are severe tensions between generations, between brothers. Of course, that’s true in every family, in fact, but it’s especially true in power families.

Why are historical subjects compelling topics for books?

I like the comment of Benjamin Disraeli, the British prime minister, who said, ‘When I want to read a book, I write it myself’. And that’s basically what I do too. With this world book, it was the same thing. I wanted to write something that was written in the way that I wanted to read. I like writing about great characters. I’m a little bored about writing about long periods of peace. I’m less interested in things that happen within England and more interested in things that happen abroad.

Having worked as a journalist, how does that inform your work as a historian, if at all?

I’m a great believer that journalism is very good training for writing both fiction and nonfiction. I was very lucky, because in the early 1990s, I was writing about the fall of the Soviet Union. I was a war correspondent in Chechnya and Georgia and all these places. It’s great training for a journalist to see how empires fall. And it was a great training for writing this book, that I’d seen a great empire fall. It’s very unique and lucky. And that’s one of the reasons why this book ends on the day of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. And I really wanted to bring it up to modern times, because it’s kind of fun writing about something that’s almost up to date.

Isn’t there a danger of some things being too close to write about with enough historical distance?

Of course. But it’s also fun to do. The closer one gets, the more likely one is to get the perspective wrong. And the perspective is the whole point of a world history. Nonetheless I’ve made a massive effort to reject presentism and reject following the blind fashions demanded by ideology of all sorts.

What is it about Russia that keeps you hooked on writing about it?

It’s a strange thing, I guess I have to realise I may never go back to Russia again. Russia really dominated the last 30 years of my life. I’m fascinated partly because its history is so dramatic, and dark, and complex. But also, my mother’s family are from the Russian Empire, and they escaped in 1904. When I was a little boy, I remember hearing about Russia and the stories of them coming out. And I think that was the start of my obsession with Russia.

Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. Had you seen that coming?

You can read about this in my Romanovs book, for example. The book has a conclusion about Putin, it just says, the imperial state of mind still dominates Russia. And that was published seven years ago. So, when he started amassing forces, I’d read carefully all the articles he wrote, the speeches he gave, and much of it mentioned Prince Potemkin and these characters from the 18th century that I had written about. And in fact, Putin had read Catherine the Great & Potemkin, my book on the subject, which is how I got access to the Stalin archives originally. So I took it seriously. A lot of people in England said, ‘Oh, the Russians will never invade because they like sending their children to British private schools, and they like being in London shopping in Chelsea.’ And I just said to them, ‘That’s what you think England is all about.’ But actually what they’re interested in is power in Russia, and Russian power in the world, which are two very closely allied things. And so I believed that he would invade. I wasn’t surprised when it happened.

And how do you see it ending?

In two ways. Either a stalemate; we’ll negotiate borders, a bit like the borders between Pakistan and India in Kashmir, or the borders between Israel and the Arab states negotiated in 1949, which will become the borders of Ukraine. And Ukraine will have to build its westernised democracy within these borders. But a better outcome would be if Ukraine manages to actually defeat Russia, because that will defeat an idea of Russia that it has of itself too. It will defeat the imperial, autocratic state of mind in Russia. That would be a great achievement, and an advantage for the world too. And if there was an actual defeat, that will also probably bring down Putin and his system. We hope.

You mentioned Putin allowed you access to the Stalin archives. How did that happen?

When I published that book no one had really written much about Catherine the Great or Potemkin [she ruled in Russia’s golden age and had several lovers, including a statesman and military leader called Grigory Potemkin]. Because they’d been completely out of fashion for 70 years under Soviet rule. And under Nicolas II and the Victorian czars, they were very embarrassed about the sex lives of that couple. They’d been kind of written out of history for the first two centuries. Essentially, Putin read the book. Putin was interested in the subject. In the year 2000, Putin was already fascinated by Ukraine and Crimea, he was obsessed. Because he said that I had shown these characters fairly, they asked, would you like a reward? And the reward would be working on Stalin’s papers.

Has history always been weaponised? Or are we seeing more of that in recent times?

I follow some of the historical debates in India, the debate on the Aryan origins and Empire, of course. And, it’s the same everywhere, actually. Though we think of it as something new, history has always been very politicised. Many historians in the book are killed for writing history. The fact is history has always been weaponised and is incredibly powerful. One of the big challenges of writing is to resist the pressures of the present, to resist ideological straitjackets. This is a challenge for Indian historians, as well as in England and America today. As for myself, in this book, I’ve made a real effort to resist both the traditional English approach to the British Empire, for example, but also to reject the progressive ideology that has racialised all history. And that’s a big influence of American culture on us. I’ve tried to resist both ideologies because they’re both wrong. I think all ideological approaches to history make no sense.