How non-violent was Gandhi?

Jacques Le Goff, the renowned French historian, springs to mind. In one of his books, he historicised the bitter disputes that pitted Protestants against Catholics in the sixteenth century. During these conflicts, Protestants vehemently criticised Catholics for their belief in Purgatory, which Martin Luther termed as "the third place." This "invented" realm—the "other world"—is not mentioned in the Bible.

Let’s consider another “invented” realm: Direct Action. This term is deeply ingrained in the collective memory of South Asians. Contemporary archives reveal that Direct Action is a significant part of the subcontinent’s political and mobilisation“Bible.” It has been used by the Congress, Communists, Unionists, Muslims, and almost everyone in the past. It’s a striking slogan, a steel intent, and a catchy headline for the press. If only we had a historian like Le Goff, we could have written a history of Direct Action, as he did with ‘The Birth of Purgatory’.

However, with our historical plight, direct action gets encapsulated in a single date: August 16, 1946. It was a day of protest by the All-India Muslim League to demand the creation of a separate Muslim state, Pakistan. The day became indispensable to the national histories of both India and Pakistan, with synonyms like the Great Calcutta Killing. Four days of massive Hindu-Muslim riots in Bengal’s capital between August 16 and 19, 1946, resulted in 5,000 to 10,000 deaths and 15,000 injuries. These riots are likely the most notorious single massacre of the 1946-47 period, marked by widespread violence across the subcontinent. East Bengal, Bihar and others joined in.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

Direct Action was not meant for Calcutta alone. It was sub-continental and intercontinental. In Bombay, it was about a complete hartal. Muslim students were kept out of schools and colleges, and shops and business houses remained closed. Mohammad Ali Jinnah addressed a meeting at Mastan Talao, Nagpada, immediately after the Jumma prayers. Ensuring communal harmony, League volunteers moved about persuading Muslims not to gather in the streets. Local newspapers thus reported. Five thousand miles away in London, Leaguers led by the president of the London branch, Mohamed Abbas Ali, marched through the city’s principal streets for two hours. It was quiet and peaceful.

The Beginnings of Violence

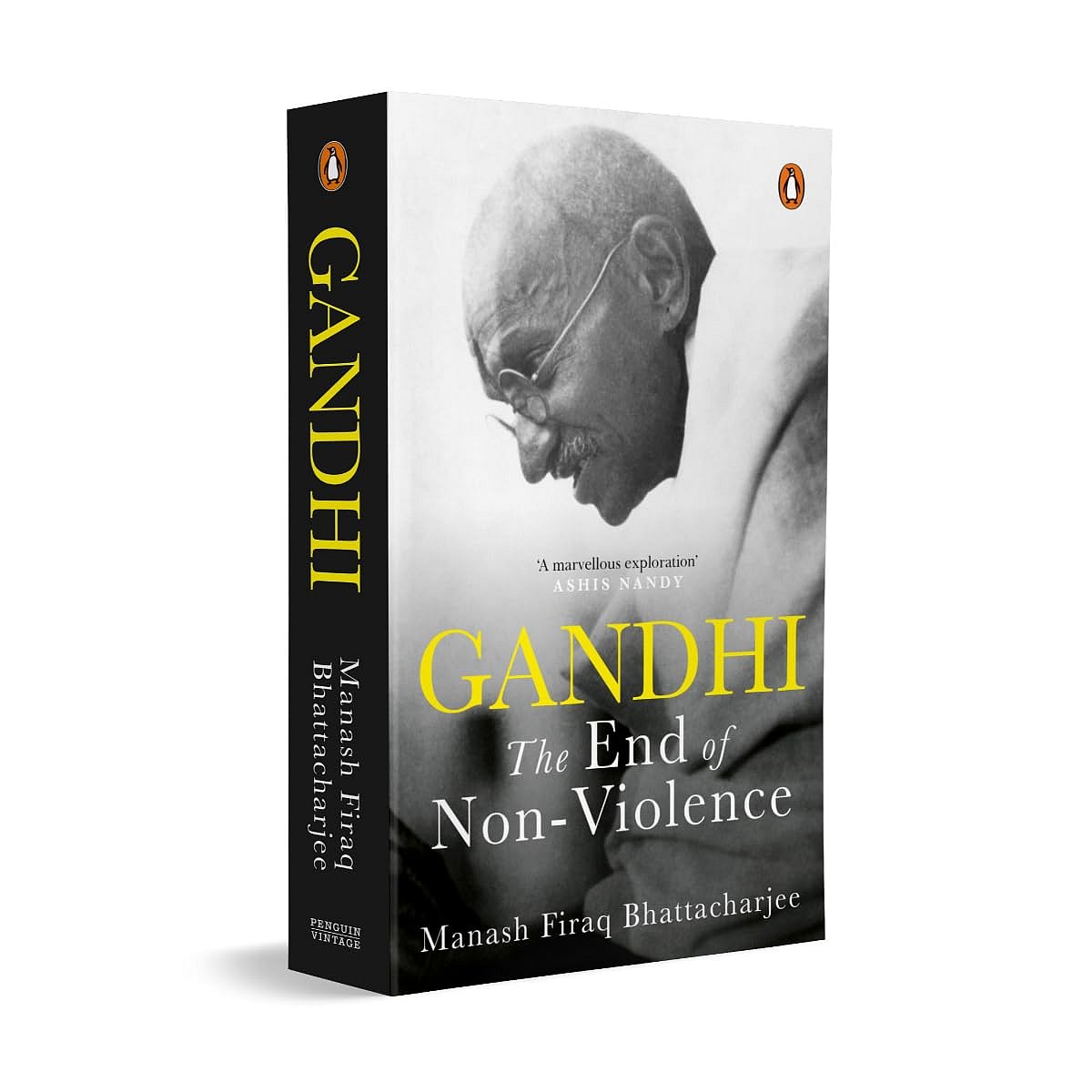

Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee is back with a brilliant read. The book promises to be “a combination of intellectual history and political history.” What’s the subject? The last phase of Gandhi’s life. It begins with the winter of 1946 and ends on 30 January 1948. In between, it celebrates Gandhi’s heroics in Noakhali, his move to Bihar, his return to Calcutta, his time in Delhi and eventually his assassination at the hands of a Hindu terrorist. It meticulously records the details. Never missing a bit. The form is the essay. The sub-headings are pensive. The book reads like a long essay with thought-out breaks to implant the axes of space and time. The author clarifies right at the outset that he has not set himself up for a larger story of partition. He only thinks about “Gandhi, Partition, non-violence, violence, genocide, ethics and truth.”

Bhattacharjee writes beautifully. He is a stylist. His frequent dabbling in poets and lesser-known quote makers, and philosophers is endearing and enlightening. He comes out as a restless theorist who is out there to encapsulate the contradictions of Gandhi well enough. Readers are acquainted with the likes of Étienne Balibar, Emmanuel Levinas, Jacques Derrida, et al. We have known individuals like Ambedkar, Savarkar, Aurobindo, Sharddhanand and Vivekanand. We also get to know the Finnish poet and aphorist, Pavvo Haavikko. On listing the kinds of histories-- two or four-- Bhattacharjee had many options to choose from. By going with Haavikko’s “the pathetic and the factual” histories, he brings fresh air laden with deeper perspectives. The book is full of such improvisations. Spread over five chapters with a flowing and rich introduction, the book makes for a serious reading. Not a page-turner. Not thefun kind.

Having discussed the eloquence, now some matters of fact. The last days of Gandhi are a well-discussed trope. In the ever-expanding Gandhiana, the heroics of Noakhali and its thereafter have been often discussed. Of course, through the partition literature. Contributors like Suranjan Das, Rakesh Batabayal, Mohammad Sajjad, Papiya Ghosh, Debjani Sengupta, Anwesha Roy, and Joya Chatterjee immediately come to mind. Bhattacharjee has engaged with most of them and enriched his position and of his interlocutors. However, a petty question remains. Why has the “peace mission” of Gandhi had such a finite and limiting history? Is Noakhali crucial to us like Ceaser crossing the Rubicon? It seems, just like the Rubicon, Noakhali became a metaphor on which the hopes of non-violence and peace were preserved. Historians could’ve asked why Gandhi never travelled to the western borders, where the partition carnage became fiercely unforgiving within a few months after Noakhali. Delhi, anyway, was closer to Amritsar and Rawalpindi than Noakhali and Patna.

Bhattacharjee, as an act of intellectual history, is right in asserting that “Gandhi was un/doing politics, and un/making history.” His choice of focusing on a specific political moment sharpens the thesis. Gandhi in his book materialises as a “thinker-practitioner”. But as it often happens with intellectual histories done for predominantly semi-literate peasant societies, the context of the state and society goes missing. The excessive dependence on the “Collected/Selected Works” makes these histories Carlyle-like. We will return to it.

Anatomy of Communal Violence

Bhattarcharjee begins with Gandhi’s first public statement on ‘Direct Action Day’. Speaking from Sevagram, Gandhi opined that Calcutta was “an ocular demonstration of what direct action is and how it is to be done…” He also called it “senseless violence”. This is the entry through which the author deep dives into his thesis. The problem with such an enterprise is the urge to come out with a model that defines violence and its non. Definitions are heuristics, a compromise, in the absence of a more fundamental understanding of things. That’s where the book gets stuck.

Categories. Kinds. Classifications. Were the rioters in Calcutta and Bihar only people: Perpetrators and Victims? Hindus and Muslims? Bourgeoisie and Proletariat? Zamindars and Peasants? Menacing Crowd? Goondas? Can we have the same categories for, let’s say, Moplah (1921)? For historians who have neatly categorised Moplah as “rebellion”, what stops them from meting the same treatment to Calcutta and Bihar?

Gandhi, in 1921, once said how his heart bleeds thinking “Moplah brethren have gone mad.” After three decades, everyone had gone mad in the subcontinent. However, our leaders, the history from above kinds, never learnt their lessons. They kept thinking in neat categories like most historians do today. They avoided the mess that people and their actions are.

It is very clear in the book. Even though the author depicts the Gandhian endeavour as a win, the bruises of loss are too stark to be missed. Gandhi, in his “last phase”, had gone so far on the highway of sainthood, and any alleyway to politics was not evident to him. The author, like many others, seems to celebrate it, others might disagree.

Since the author avoids locating the thinker-practitioner under the State, the politics of it, in which he lived, a few sources go missing. Think, for example, the various officials appearing as sources of history writing. One Lt Gen Tuker, Eastern Command GOC, comes to mind. In his memoir, Lt Gen Tuker recorded theaftermath of Noakhali Remembrance Day in Bihar. Women and their babies were cut up, butchered, with an obscene devilry that a civilised people cannot even conjure forth in their imagination. Tuker reports that when he asked a group of Hindu soldiers why they used their weapons against the gangs of killers (co-religionists) with such effect, they stated, “they would have liked to wipe them out after what they had seen.”

Similarly, responses to Bihar violence in November 1946 read differently when one approaches it through “colonial sources” like Wavell: The Viceroy’s Journal. AP Wavell, touring riot-torn Bihar, scathingly recorded his assessment of the local Congress leadership, referring to the chief minister, Shri Krishna Sinha, as a “gangster”. While appreciating that Nehru was trying to “check the troubles,” Wavell told Sinha in person “that his government has disgraced and discredited Bihar; that it was criminal folly to allow Noakhali Day to be celebrated… lowering the morale of the Police and [that,] in failing to control the Press, [his government] had led directly to the present tragedy.” Thankfully, Bhattacharjee relies on Mohammad Sajjad’s brilliant work on Bihar and some of these sources to rescue the tensions and contradictions of the times, not falling for the pitfall of having a clear-cut definitional communalism.

Even Gandhi sounded astounded on March 7, 1947, while referring to the communal procession in Gaya where slogans of retributive violence were raised. Gandhi remarked: “I have heard that these people shouted Mahatma Gandhi ki Jai while carrying out the massacre.” Imagine, “‘Noakhali ka badla le karrahenge [We will avenge Noakhali]” with “Mahatma Gandhi ki Jai”.

Just 12 days later, Gandhi asked his Congress workers, “Is it or isn’t it a fact that quite a large number of Congressmen took part in the disturbances? I ask this question because people are making this allegation.” Even in these deadening depths of a crisis, Gandhi was keener on the moralism, and not the everyday-ness of the politics and mobilisation. He knew that a few decades back, in one of the first debacles, a few men burnt a thana in Chauri Chaura with “Mahatma Gandhi ki Jai” on their lips.

A Book for Contemplation

Bhattacharjee has given us a book for contemplation. Pyarelal, Nirmal Kumar Bose, and Syed Abul Maksud join hands with the descriptions of Mridula Gandhi (Manu’s diary), making the work descriptive and animate. Especially, Manu’s Diary from December 1946, when she joined Gandhi in Noakhali, until January 30, 1948, when he was assassinated, make the work amply rich and most of all, human.

It makes a compelling, and mostly emotional read if you agree with the author’s declaration that “It is not an exaggeration to say that Gandhi’s peace mission in Noakhali, Bihar and Calcutta has no parallel in the history of the violent twentieth century.” But if you are not merely content with the Noakhali peace or a deputation handing over a note of assurance to Gandhi in writing that there won’t be riots in Calcutta in August 1947, you seek more. A reader is well within their rights to ask why the riots, and the naked dance of communalism never stopped in contemporary India. A celebratory history of the Gandhian peace mission isn’t enough to answer it.

A reading against the grain suggests that many of these categories that danced naked, massacring each other, were created during the times when they should’ve been contained and neutralised. The author reminds us of March 28, 1947. In Jehanabad, Bihar. Muslims requested Gandhi not to bring up Noakhali in his speeches in Bihar as it would incite Hindus. Bhattacharjee reports, “Gandhi disagreed, saying that he had restricted himself from speaking much on Noakhali, but that Muslims should not expect him to keep silent on the atrocities in Noakhali.” Gandhi said that the ‘sins’ of both communities were of the “same magnitude and equally condemnable.”

In another instance in Bihar, Gandhi took along the traumatised children with him to walk the streets and witness the scenes of violence. The author, in cognisance with Gandhi, sees it as an act of overcoming fear and affirming the right of children to reclaim their space in devastated neighbourhoods. Can we all agree?

Can we concede that often, leaders from above didn’t understand the people from below? Like other Indian leaders, after the Direct Action Day, Jinnah had denounced the “fratricidal war.” A news magazine remarked, “Most observers wondered how Jinnah could fail to know what would happen when he called for 'direct action.'” Was Jinnah unaware that direct action in Calcutta would play out differently than in Bombay and London? Similarly, were Gandhi and Nehru heedless about how their people went mad?

Historians, as a group, often remind us of that one weary police officer in Calcutta in August 1946 who told a newspaper: “All we can do is move the bodies to one side of the street.” A clear-cut definition of communalism as “communal politics intercepting class antagonism” hasn’t led us very far. It just moves the bodies to one side of history.

Bhattacharjee could be read in several ways. His take on the “last phase” of Gandhi cannot be bettered soon. But those who care for the mounting dead bodies on the streets would like to exchange moralism for some pragmatism in history writing.