Himalayan Wonder

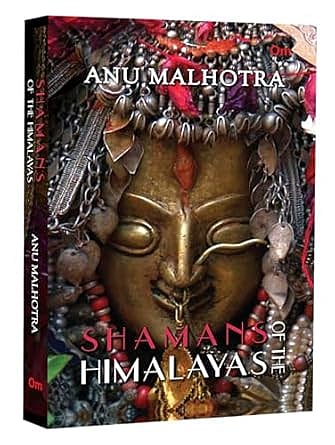

AS YOU WOULD EXPECT in a book written by an acclaimed filmmaker, Anu Malhotra’s Shamans of the Himalayas is filled with striking images of seers, oracles, exorcists et al from across the Dev Bhoomi (literally, land of the gods) in Himachal Pradesh’s Kullu Valley. But for Malhotra, the journey of documenting these traditions began with a man blocking her shot during a work trip to Himachal. Devotees of Hadimba Devi, the patron goddess of Manali, were carrying a palanquin bearing the idol and dancing to music, when suddenly Malhotra’s camera-line was blocked by a man who approached the palanquin with a sense of purpose.

“Then, to my astonishment, the man began trembling, shaking violently, and suddenly started jumping up and down, shouting aggressively. The villagers, while giving him space, gathered around him, listening respectfully. He stood before the palanquin, gesturing animatedly as he addressed the crowd. I watched in amazement this strange scene. His once unremarkable face had transformed—now thunderous, with flashing eyes and exaggerated gestures.”

This encounter, recalled in the book’s prologue, encouraged Malhotra to engage with Dev Bhoomi and its belief systems from a place of deep respect and intellectual curiosity. Whether one “believes” in shamans or possession or the idea of alternative consciousness is beside the point. These traditions exist, they are incredibly important to millions and this by itself makes them worthy of the kind of critical attention that Malhotra brings to the endeavour. Shamans of the Himalayas is based on her documentary series of the same name, telecast by Discovery in 2013. While shooting for the series between 2008 and 2010, the filmmaker spent a lot of time immersed in the lives of these shamans and their followers. During an interview, Malhotra spoke about how her training as a documentarian (she has made several award-winning travel films and documentary series since the 1990s) was a key to the process.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

“I have been documenting tribal cultures in my work for over 30 years now,” says Malhotra. “In the early 2000s my films on the Apatani tribe of Arunachal and the Konyak people of Nagaland were released. When I was working on those projects, I understood that you have to gain a deep and intimate knowledge of the cultures that you are capturing on your camera. There has to be a sense of humility about the experience. You have to earn respect, you have to earn trust and I think I am a non-judgmental, open-hearted person.”

Indeed, the level of access Malhotra is readily given across Dev Bhoomi is remarkable. She describes the everyday lives of the villages and small towns who coalesce around a local deity—and often, this deity seems to have a say in just about everything. Marriage dates, job prospects, mystery ailments; the deity is consulted in everything and Malhotra’s descriptions of the same are one of the book’s principal pleasures. They also emphasise an important philosophical aspect of the whole ecosystem—this is a living deity. The animate status of the deity is not just taken for granted in Dev Bhoomi; it is often the basis for an entire administrative setup.

“Because the deity is considered to be a living, breathing entity,” Malhotra says, “There is a whole office of sorts devoted to their needs. The pandit, whose family has been serving this role for generations, is the overall man-in-charge. Then there is a store manager who takes care of the idols and the deity’s jewellery and so on. There are musicians who have been trained in the songs favoured by the deity. In this way they all serve the will of god.”

As Malhotra is careful to note in the book, hyper-local, region-specific traditions, shamanistic or otherwise, are shaped in part by their encounter with Brahminic rituals. Often, the resultant ‘hybrid’ modes of religious practice cannot be pigeonholed as either orthodox or progressive. This aspect is brought out beautifully through the story of a female shaman (a rare phenomenon), a middle-aged woman named Tuli Devi. Tuli is a medium for Navdurga Ma, a composite Devi representing the nine forms of the goddess worshipped during the nine days of Navratri. In a male-dominated world, she has carved out a niche for herself, with her unique variations on shamanistic practices. And yet, Tuli only began her journey when she realised that as a woman, she did not have unfettered access to her cherished deity. On certain days and during certain rituals, women are not allowed. Necessity dictated the direction in which culture flowed, something also suggested by the fact that many of Tuli’s followers (as Malhotra points out) are lower-caste women, migrant labourers working in Himachal. Far from home, they lack support structures and to them, Tuli is, depending on the day of the week, priest, teacher, healer, psychiatrist and probably a few other roles we are not privy to.

“For me Tuli was one of the most special stories in the book,” Malhotra says. “She is a true original, not just in the way she conducts herself but also in the way she created her own little traditions, her unique way of doing things. The fact that she is a female shaman, a rarity, is very important to her followers. When they receive the word of the goddess through Tuli, her female followers feel like they have one of their own to turn to when they’re facing any issues in life.”

As a filmmaker, Malhotra is aware of the fact that possessions and shamans are quite ‘trendy’ at the moment, from a pop culture point of view. Several mainstream Indian films have featured similar depictions in recent times—Stree and its sequel Stree 2 spring to mind. The Kannada blockbuster Kantara featured an extended climax where actor Rishab Shetty enacts divine possession (by the deity Guliga Daiva) in a memorable, much-lauded performance. Indeed, during our interview Malhotra mentions that for her, Shetty’s performance was the closest an actor has come to showing the audience the effects of divine possession. But she is also aware of the responsibilities that creators have when it comes to depicting indigenous belief systems.

“James Cameron had to create a Pandora in order to discuss issues of colonisation and environmentalism et cetera,” says Malhotra. “But I always say that in India we have so many Pandoras of our own, which we know so little about. These are cultures that can teach us so much about our contemporary lives and how to improve them, how to be healthier, happier, more compassionate and less wasteful.”