Fawad Fever

AS 2014’S FEEBLE monsoon faltered to a close, India burnt for Fawad Khan. The Pakistani actor had just crossed over into Bollywood with Khubsoorat, reducing women across the country ‘to wobbling blobs of jello’, wrote Shobhaa De in a thirsty column about ‘Fawad fever’. At the magazine where I worked, Khan’s hooded gaze from a colleague’s pinup distracted me each time I looked up from editing a story about Pakistani serials. The story’s hook was the launch of Zee Zindagi, a channel promising to bring the best Pakistani television. One of its flagship shows, the Khan-starrer Zindagi Gulzar Hai, went into reruns almost immediately after its India debut.

Much has changed in five years. As a response to the 2016 Uri attack, Zee Zindagi jettisoned its Pakistani offerings for Turkish, Latin American, South Korean and Indian programming, some of which was already in the pipeline. By 2019, rising tensions between the two countries led to a widely publicised demand to ban all Pakistani actors from working in India.

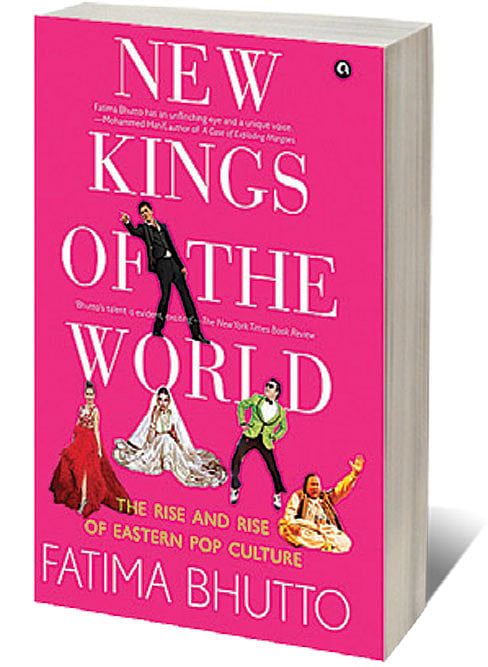

Khan or no Khan, it’s remarkable that a channel like Zindagi exists at all. Its imported shows, with dual Hindi and English audio feeds, include Fatmagül (Turkey), Snowdrop (Ukraine), Total Dreamer (Brazil), Boys Over Flowers (South Korea) and A Love Story (Turkey’s Bir Ak Hikâyesi, itself an adaptation of South Korean drama Sorry, I Love You). The rise of what Fatima Bhutto calls ‘Eastern pop culture’ is the subject of her latest book, New Kings of the World, in which the Pakistani writer reports broadly on three mainstream genres: Bollywood, Turkish serials called dizi and K-pop. The history of Zee Zindagi hints at the challenge of taking on such diverse topics in one project.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Though its title suggests a global overview, New Kings is best taken as a series of pieces exploring the journeys of these genres, Bollywood in particular. Bhutto acknowledges the brevity of her sections on Turkey and Korea (the Hallyu chapter is cast as epilogue); still it’s worth noting that about half the book feels like a chunky frame for a centrepiece interview with Shah Rukh Khan while he shoots an episode of Egyptian prank show Ramez Underground in the UAE. Khan’s role as Bollywood ambassador is well-worn territory, but the interview is a nuanced, fun read.

In general, Bhutto’s reported sections work best; besides the UAE, she travels to Turkey, Lebanon, South Korea and Peru (for a memorable bit about local SRK fans—though the connection between Bollywood and indigenous Andean horror films feels tenuous). Interspersed sections of exposition include useful context and data, but can be heavy-handed, like stock filters on an otherwise interesting snapshot of 2019.

In such sections, Bhutto looks (sometimes glancingly) at the role of government in cultural promotion, the rise of new distribution platforms and technologies, the issue of representation and changing audiences—but she mostly elides these observations in favour of evidence that Eastern pop culture presents a family values-driven challenge to the empty, hyper-capitalistic entertainment of its American counterpart. This argument feels laboured at times; perhaps shedding some of the ballast of political context and historical exegesis might have allowed her subjects to rise above a need to definitively map the diverse, shifting terrain she’s surveying, which she aptly calls a ‘challenge to American soft power’.

This soft power is epitomised in New Kings by almost cartoonishly ‘American’ shows like Dallas and Dynasty, lumped together facilely as examples of hollow capitalist entertainment. Bhutto doesn’t dig too deep into why global audiences, even if elite, took pleasure from these shows, and though her reporting suggests that the ‘good old Asian values’ of Eastern pop culture may be co-opted as easily by capitalist, patriarchal or patriotic agendas, New Kings is more celebratory than critical. What Bhutto captures, if not explicitly, is that the trajectory of non-American pop culture isn’t necessarily a vertical ‘Rise and Rise’, but an ongoing lateral circulation—sometimes influenced by the ‘West’, sometimes performing the ‘East’ and sometimes breaking down such boundaries.