Classic Power Play

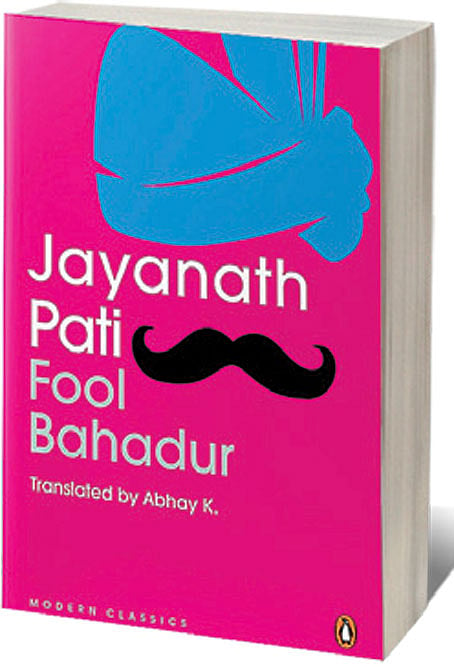

FOOL BAHADUR is the first extant novel we have in Magahi, a language spoken in the eastern regions of India, notably, Bihar, Odisha and Jharkhand. Magadhi, one of the more dominant Prakrits that flourished from the third century BCE onwards, generated many modern Indian languages, including Axomiya, Bhojpuri, Odia and the language we now call Magahi. Magahi always had a rich oral tradition of tales, sagas and folk songs but it was only in the twentieth century that written literatures began to develop. Jayanath Pati, who was a scholar, newspaper editor and writer, was one of the foremost figures of this transition, writing at the same time as Munshi Premchand. In fact, Fool Bahadur was published in the same year, 1928, as Premchand’s Gaban. Pati was also a lawyer and a committed nationalist, using his newspaper as a medium to spread ideas of Swaraj and self-determination.

Although Fool Bahadur is set in the tumultuous decade of the 1920s, the action takes place not on the national stage but in a district administration headquarters in Bihar, in the complex corridors of the Raj’s colonial administration, among lawyers and collectors and their deputies and assistants and all manner of high- and low-ranking policemen. Everyone is jockeying for position, each wants to be promoted to more power, more pelf, to the next professional designation and the next civic title, to the chance of getting larger bribes and wielding a bigger stick, as it were. Some part of the pleasure in reading Fool Bahadur lies in the recognition that even one hundred years later, the now fully Indian bureaucracy has lost none of its somnolence and remains the primary arena for petty corruption as well as full-blown malfeasance.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Fool Bahadur may purport to be a ‘novel’ in the large landscape of people and places that it suggests, but it is, in fact, a short story, numbering barely fifty pages in English translation. The plot is simple so I will not describe it at any length—suffice it to say that it involves nawabs and babus and mukhtars and bahadurs, there are tawaifs, those glorious perfumed creatures of intoxicating beauty and whimsical behaviour, for without them, every story from that period and that region would be dull and lifeless. There is even a twist at the end of the tale, a joke that perhaps meant more at the time of its writing than it does now.

Abhay K’s translation is breezy and confident, he is clearly enjoying the story anew as he moves it into another language. For my taste, there are rather too many footnotes. However, most of them explain bureaucratic ranks and designations and since the story is predicated on precisely these positions within the power structure, I suppose the translator had little choice. Abhay K also provides us with a detailed and enthusiastic account of Magahi’s linguistic history in his Introduction.

The 1920s and 1930s in the South Asian subcontinent were also a time of great and varied literary output— nationalist, realist, didactic, romantic. In Hindi, this period of vibrancy, political awareness and experimentation was supported by literary magazines and small presses. No doubt Pati felt a part of this ferment as a writer—his lost first novel, Sunita, resonates with Premchand’s Nirmala, in which a young girl is forced to marry a much older man, resulting in a painful tragedy. Pati was also consciously creating progressive literature in Magahi. Fool Bahadur is clearly meant to expose corruption as well as human greed and vanity. However, it seems to fall between satire and realism, giving us the full pleasures of neither. What it does do, nonetheless, is remind us, yet again, that much has been happening for at least a century in Indian languages that are not hegemonic or dominant, that we were always as multi-vocal as we are multivalent in our many cultures and civilisations.