Arundhathi Subramaniam Writes about our Crazy, Freedom-loving Ancestors

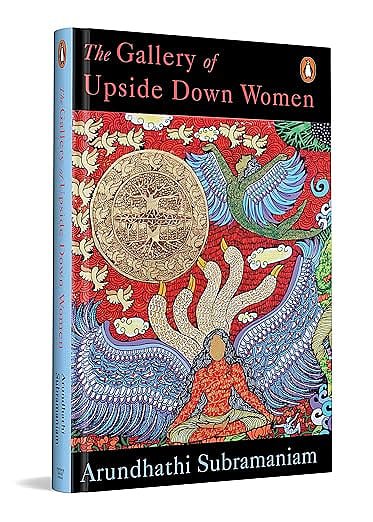

In Arundhathi Subramaniam’s newest collection, The Gallery of Upside Down Women, poems express a desire for a more permissive, imaginative world—one where faces are allowed the full spectrum of expression, where people are entitled to their quirks and harmless hatreds, and where one accepts with humility how little one truly knows. With inventive premises and striking turns of phrase, she questions, among other groups, the literary status quo—which poets and philosophies are deemed palatable, what motifs are defaulted to without an understanding of why, and what it means to write what one cannot possibly endure. The collection highlights language’s role in our self-deceptions and our undeserved erasures of others.

Much of the overt focus of these poems is on female mystics of whom Subramaniam has previously written in Women Who Wear Only Themselves (2021), a book of essays on spiritual travellers, and Wild Women (2024), an anthology of poems by Indian female mystics through the ages. But, here, the encounter is far more intimate. In skilful persona poems, she reanimates the “crazy, freedom-loving ancestors” she wishes she’d known sooner, inviting us to see them and their utterly human desires and failings as kin. She shows us how the world may perceive their lives as more deviant than they are in actuality. For these women, it was often the most ordinary difference in opinion, the slightest nuance, that set them on non-traditional paths.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Sacred verse has long entwined the mystic with the erotic, and The Gallery follows in that tradition—exploring the taboo desire to be tainted, to lose oneself to the god of no shame. Subramaniam’s portraits of mystics—Karaikkal Ammaiyar, Meera, Akka Mahadevi, Avudai Akkal—are steeped in a sensuality that heightens our awareness of the spirituality at stake. In ‘Where the Yoginis Wear No Heads,’ Lakshminkara sheds all her silks and all prospects of marriage, and with theatrical madness smears herself in ash from pyres. Avudai Akkal recognises “the master cannot / stay away when he senses ripeness.” Meera is similarly honest in her desire to be “stained” in becoming one with her god. The sanctity of god crumbles in these poems. These women reject sanitised reverence in favour of embodied truth and messy surrender. The contemporary and the mythic bleed into each other—into poems of fruit and sewing, aging flesh and cosmic memory, domestic acts pulsing with the quiet holiness of the everyday.

There is also space for quieter, but equally unorthodox, devotion. In ‘Just In Case,’ we meet those who leave nothing to chance, who pay their respects at every place of worship, regardless of denomination. It is as effective as following a single path, yet there is something wonderfully optimistic and expansive in this practice of communing, however busily, with each one. The poems provide a humbling reminder that the ways are myriad, but each is steeped in its own private logic.

A strain of strangeness anchors the collection. ‘The Great Mother’ honours the experience of seeing one’s mother grow old. In the poem, the daughter observes a powerful and eerie presence within her parent in that obliterating interlude before death. In ‘Some Said He Looked Like James Dean,’ a companion image is offered—an aging man’s next life is seen by his wife. A woman in a yellow saree remains outside the Taj Mahal and a man keeps the fabric of the universe sewn till one day he doesn’t. These brief portraits read like “graffiti on the stainless”—their significance at once devastating and fleeting.

There is no easy distance between the speaker and the mystics—no scholarly remove. Instead, there is a bearing-down into the body. The everyday becomes uncanny; the everyday becomes divine. I finished the book feeling unsettled in the best way—Subramaniam doesn’t hand us neat answers. She dismantles altar-like gestures around devotion and invites us into radical agency, into living that is reverent not in spite of dirt and doubt, but through it.