Anees Salim: The Heirs of the King

IN A PALACE an old king lies comatose, life slipping away from him. At first, we don’t know anything about the place, the period, or even whether this is a “realistic” tale, but the storytelling has a fable-like quality: it is divided between many narrators, all of whom are the king’s progeny.

The official sons speak first: the rival princes Moazzam—fat, alcoholic, childlike —and Azam, outwardly more poised but with a small addiction, or obsession, of his own. This is followed by a din of voices of illegitimate children. There is the stammering Hyder who is employed as a nurse in the dying ruler’s room: “The spacious bed looked like an oc... oc... ocean, and he, withered and tiny, a blue bedspread pulled up to his chin, like a man about to be drowned.” There is Zuhab, conceived in a village when the king’s train broke down there many years earlier. A young poet named Shahbaz, who lives in an alley, and the marble-playing ghost of his childhood friend Sultan, who died of the black fever at 13. Muneer the tailor, hoping to stitch a new fez and take it to the palace. The enigmatic Owais, constantly trying to get through to Cotah Mahal on the phone.

And there is Humera, the only woman in the group, whose mother wasn’t just a concubine or mistress but the king’s “lover”. Among the illegitimate children, she alone received birthday greetings from her father.

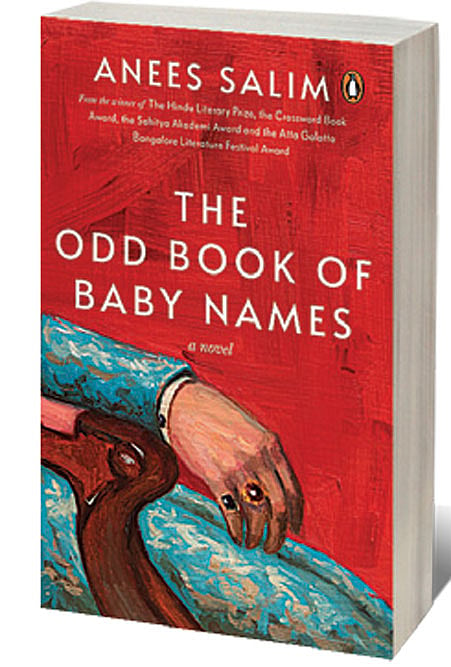

Thus unfolds Anees Salim’s sixth novel The Odd Book of Baby Names, taking us back and forth in time as personal histories—some of which intersect—are revealed. We also learn about a slim book in which the ruler had recorded the names of all his children—perhaps over a hundred of them. (“What necessitated such a cryptic register was the history of poor memory that ran in the family like an incurable disorder,” Azam tells us, a line that recalls themes from Salim’s earlier novels, especially The Blind Lady’s Descendants, 2014.) As names from this private journal are listed, the reader might inevitably become curious about the lives of those many other children. How big would a novel have to be to accommodate all of their stories?

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

It would have to be an epic, a baggy monster—but that isn’t the kind of writing one associates with Salim, who is a master of the small, intimate story that grows in the telling. Over the past decade he has been one of our finest novelists, winning accolades for a style that combines chatty, colloquial prose with sharp and poignant observations about families, communities and the conflicts faced by individuals within those groups.

As a long-time fan, I felt the special pleasure of sinking into a new Salim novel as soon as I opened this one: the mixing of moods, from throwaway humour to heartbreaking insight, the unexpectedly rude asides. Here is a description of a pitcher covered by a jacket in an attempt to make it look less ugly—but instead giving it the appearance of “a destitute man with amputated limbs, piddling drip by drip onto a bedpan”. And here is a depressed young woman pretending in turn to be herself and a “doctor who mended minds”, switching from one chair to another on opposite sides of a table, even ruffling her own hair. A funny passage where Shahbaz sings a love song that frightens a child. An irreverent but accurate-sounding description of a dead man on a couch, as a child might see him: “Bada Topiwalla lay almost smiling at the ceiling like saying hello ceiling how are you.”

As often happens in Salim’s work, the universal and the very particular move together: the clamour of competing voices represent a gamut of human experi-ences, but the characters are all Muslim, and there are culture-specific references, such as a passage where two boys anger a Quran teacher with a prank. As more details creep in, one gathers that the story’s present day is sometime in the late 1960s or early ’70s: there is a reference to a conver-sation set a few years after Nehru’s death; another reference to the king being on the cover of Time magazine in the 1930s. It is tempting to play connect-the-dots, to wonder if this ruler is a fictionalised version of a real figure (Jinnah would be one obvious choice), but such inferences aren’t necessary for a deeper appreciation of this story: this is not as pointedly allegorical a novel as, say, Salman Rushdie’s Shame or Midnight’s Children.

There are, of course, larger themes at play in this story of a ruler and his “children” from various classes and walks of life, forming an orchestra of aspirations and delusions. (“Each name had a meaning, a purpose” goes a passage that’s ostensibly about a large tree full of nests, “When all the birds sang together, the air was heavy with the sound of 100 maracas, probably 1,000.”) In a moving scene, one of the sons recalls his old father thinking he was once a circus-owner rather than a king. Perhaps any dying leader might feel similarly about his constituency. This is a story about life’s rich pageant—about our performances and acrobatics, the ways in which pleasures and disappointments criss-cross. I think of life as a game of hide and seek, one narrator says as he watches children playing that game—a boy tiptoeing up behind a girl who thinks she hasn’t yet been discovered, each face marked with a different sort of joy or anticipation.

Structurally this may be the most atypi-cal of Salim’s novels. It is the only one other than The Vicks Mango Tree (Salim’s first novel, published in 2012) that moves between multiple protagonists. In the other books, we were tied to the consciousness of a single person: the delightful Hasina in Tales from a Vending Machine (2013), working at an airport, dreaming of escaping on one of the planes she sees from the windows; Imran in Vanity Bagh (2013), an imam’s son living in a mohalla nicknamed Little Pakistan; the melancholy Amar in The Blind Lady’s Descendants, believing he was born into a doomed family, drawing morbid inspiration from an uncle who committed suicide; most recently the unnamed adolescent narrator of The Small-Town Sea (2017) who moves with his parents to the small coastal town where his father had grown up (and wants to die).

The effect of reading The Odd Book of Baby Names is trickier. One is more aware of the author’s efforts to distinguish one narrator from another (through Hyder’s stammer, for example, which gives his narration a distinct texture). Some voices are more engaging than others: I particularly liked the ones of Muneer, and of Humera and Shahbaz as their paths converge; Zuhab’s story was less interesting to begin with, but becomes more central as the book progresses—and as the narrative moves from small misdeeds to bigger crimes: from deception to possible incest to robbery to fratricide.

Much as I enjoyed this novel, I was also left with a niggling feeling of dissatisfaction at the end—as if it had wrapped up too abruptly and I hadn’t got to spend enough time with any one narrator. It’s a book of vignettes—a flash from one life here, another flash there—and engaging as the individual episodes are, Salim’s single-protagonist novels seem to have more depth. Perhaps because he is so good at chronicling a specific life over a span of time, with new revelations coming at intervals (while we are also allowed to conjecture the unreliable aspects of the narrative). One of this book’s most funny-sad descriptions is that of the unconscious king’s farts playing “a sad tune” (perhaps like a jester with a bugle in that circus?) and providing the only sign that he is alive. It made me wonder what this novel might have been like if his had been the sole anchoring voice, with the others floating around it as an accompanying chorus.