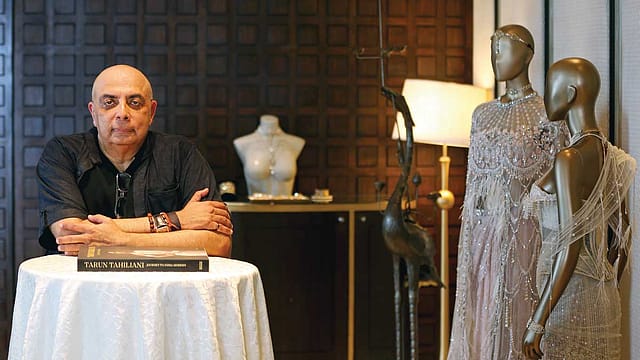

Tarun Tahiliani: The Gentle Rebel

THE PASSAGE OF time is subjective—sometimes crawling, at other times sprinting. For Tarun Tahiliani, time has passed much too quickly. The Delhi-based couturier recently marked 30 years of running his eponymous label, in tandem with his showcase at India Couture Week (ICW) 2025. The daylong event started with a pre-show lunch and finished with an evening presentation at The Oberoi, New Delhi which is also marking its 60th anniversary. The luxury hotel chain shares a special relationship with Tahiliani as he designed the staff's original uniforms.

The collection, titled, Quintessence, spans all his signatures. Think embellished corsets and dresses that brought 1920s flappers to mind, sensuously draped sheer ensembles, lehengas and sarees showcasing the fashion house's take on Kashida embroidery and Pichwai art. Embellishments abounded, from intricate embroidery to Swarovski crystals (a longstanding Tahiliani favourite) and pearls to the embellished red and gold bridalwear that continues to dominate Indian couture. "We want to focus on the core experience of luxury inside out," Tahiliani had said during the pre-show lunch, "in everything from the way you get in, the olfactory, the sound, lighting and the experience of seeing the clothes." Scenographer Sumant Jayakrishnan brought alive a salon style presentation, reminiscent of early 20th-century Parisian couture shows.

Tahiliani calls couture a "research lab to do things," to explore new techniques, ideas, and the limits of what needle and thread can achieve. "The couture and bridal buyer in India has become more discerning. Whether it's beautiful is subjective, but we want the clothes to flow. It's about fit, and luxury being in your own skin," Tahiliani adds. "We are in a different position to do that, from even five years back. We've learnt a lot since."

Five years ago, Tahiliani celebrated his studio's 25th anniversary—but that moment, marked by soirees and a coffee table book launch, has turned into a pitstop in his journey. In 2021, Indian fashion conglomerate Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail Limited (ABFRL) announced a strategic partnership with Tahiliani, acquiring a stake in the couture business and inking a deal to launch Tasva. A contemporary premium Indianwear brand for men, Tasva has over 60 stores across India and has brought Tahiliani's signatures to a new audience. Last year, during the October edition of Lakme Fashion Week x FDCI, Tahiliani also debuted OTT, a luxury pret-a-porter label for contemporary apparel celebrating India Modern, an aesthetic that has come to represent designs that reinterpret Indian textiles and crafts for a global 21st-century audience.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

IN 1987, TAHILIANI—a Wharton Business School graduate—and his wife, Sailaja (known to most as Sal) started the multi-designer store Ensemble. "I'd nothing to do with fashion," he says. "I was selling oil field equipment, which was our family business." Sal had modelled, from Pierre Cardin in New York to campaigns for the saree brand Vimal where she met the late designer Rohit Khosla. Conversations with Khosla, who Tahiliani calls "a godfather to all of us", sparked the idea for Ensemble, which began in an empty space in the Lion's Gate (Fort), Mumbai—where the store remains. Now helmed by Tina, Tahiliani's sister, it has stores across the country and retails some of India's biggest designers.

A few years later, in 1990, Tahiliani enrolled in a programme at Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) New York. Education felt imperative as he discovered his interest in draping and a desire to refashion it: "If I didn't know how to cut, or the principles of it, how could I explain it to my tailors?" He ran a design studio in New York but missed India too much. Besides, friends in finance and investment banking insisted that India was about to change in the face of economic liberalisation and he would do well to return. So, he did, launching his eponymous label in 1995 and moving from Mumbai to Delhi where he has lived and worked since—building a "crummy little studio" into a sprawling atelier in Gurugram and a network of stores across the country. Tahiliani narrates all of this in a matter of minutes, saying. "When something goes fast, it's a good sign."

Over the three decades, and more, that Tahiliani has spent—starting Ensemble and then building his own label—in fashion, the industry has bloomed from a mere kernel of an idea to a behemoth. The brand has always been part of this zeitgeist, and Tahiliani has taken both success and setbacks in his stride. When India got its first fashion week in 2000, the designer was among the key figures propelling the movement and opening the market to the concept of ready-to-wear Indian ensembles. It also paved the way for international exposure. In 2003, Tahiliani showcased his designs at Milan Fashion Week, which swiftly brought orders from foreign stores.

Going through the archive of his earlier collections, one glimpses a design mind that has often worked faster than fashion in India has moved. Tahiliani has not won the market by conforming to it—but with a gentle, beautiful rebellion. If heavy bridalwear dominates Indian fashion, Tahiliani urges lightness and lehengas for dancing. If Indian couture is conflated with weddings, he changes its outline with jackets and dresses. Recalling how he once didn't want to do bridalwear or heavy zardosi, Tahiliani says, "Today, I don't mind because my bridalwear is beige. It is understated. It is what I like," he says. "You are always happy as a designer if you do what is your calling, versus what someone tells you that the market wants."

The market now is flush with fresh possibilities, and Tahiliani is making the most of it. Contemporary Indian fashion abounds in options—bridal clothing and occasion wear may still have a controlling stake, but ready-to-wear is bigger than ever, folding everything from luxury pret to handlooms and streetwear into its layers. "People have different tastes, they are exposed to different things. They are fashioning themselves differently," he says. Seeing a woman dressed in his jumpsuit at a wedding is no longer surprising. Nor is the growing demand for couture, even bridalwear, to be versatile and multifunctional. Some years ago, Tahiliani presented a Love & Relove campaign, pairing lehengas with sweaters, embroidered dupattas with pantsuits, and anarkalis with leather jackets.

WHEN OTT LAUNCHED last year, its collections instantly brought to mind the many experiments Tahiliani has worked into his oeuvre over the years: metallic dresses and Jamawar patterned corsets, the work of Indian artists printed on topwear, kantha overshirts and chikankari jackets. He is known as the master of drape, but he also incorporates a lot of Indian textiles and crafts using techniques distinctive to the studio. It is how, he says, textile traditions evolve, become more accessible and move from bridal and occasionwear into the everyday. "Our style in India is timeless. You can wear your grandmother's saree and it will look beautiful. We should retain that," he says. "I am constantly fed by what is Indian, and contemporising it. We have had to learn techniques and fitting from the West and perhaps production, but the sensibility and expression is our own."

In the years since the Covid-19 pandemic, Tahiliani has also expanded his model of artisanal collaborations. Many of his artisans have been with the studio for many years, and some even moved with him from Mumbai. But watching artisans migrate back to their homes during successive lockdowns marked a shift. "It was a big learning for us. We thought if we could do chikankari in Lucknow, why don't we do the same with other artisans too," he says. "A lot of people now work from Kolkata, Bhagalpur, Agra, Bareilly, and Farrukhabad. This was inconceivable before." Over the last few years, he has also streamlined his sprawling production into distinct departments and studios. Couture has its own team, and so do bridalwear, accessories, ready-to-wear, and menswear. Even skills such as draping and tailoring are being meticulously categorised—so every team works on an area of specialty. Archiving three decades of work is ongoing, from embroidery swatches to patterns and toiles.

But Tahiliani is far from done. He might well be enjoying himself more than ever. Ask which are his favourite collections and he speaks of his famous Kumbh-inspired collection from 2013 and the Kutch-inspired 2016 collection in the same breath as his latest designs. The Tahiliani aesthetic has found an appeal across generations of Indians—from the beauty mogul Shahnaz Husain, to young influential figures like Radhika Merchant-Ambani wearing his lehengas to her wedding ceremonies or actor Janhvi Kapoor dressed in his handwoven tissue skirt and corset, for Cannes Film Festival this year. Add to this, an ever-growing clientele seeking out his couture, draped ensembles, and other impressions of India Modern spread across multiple collections and business verticals.

"I don't have much of a life outside my studio," Tahiliani says, but it is not out of compulsion. To be with his teams every morning working on collections, to travel and visit crafts clusters from Kutch to Sambalpur, to reimagine how Indians want to dress whether they are in Delhi or in midtown New York—these are the ingredients of his fulfilling creative life.