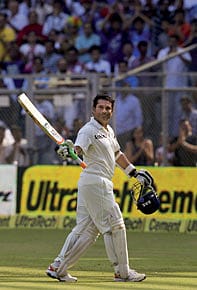

The day he was God with a bat of clay

From an India of mediocre cricket writing comes a minor classic on Sachin Tendulkar's inglorious Final Test

Reading greedily about the game is the mark of a true cricket devotee. In India, however, cricket- writing is a bastion of journalistic mediocrity, which forces the literate Indian fan to survive on a diet of foreign writing. The best of this is to be found in the London newspapers (accessible online), where the game is still paid its due respect by writers of real pedigree. The correspondents on India's sports pages are invariably trundlers—the Paras Mhambreys and Suru Nayaks of the keyboard—who specialise in a banal and un-penetrative form of medium- paced reporting, with no swing, no cut, no seam, and no variation.

The Indian cricket fan, ill-served for years by Indian cricket writers, has, at last, a reason to rejoice: Dilip D'Souza, a Mumbai-based journalist, has published a book called Final Test, on Sachin Tendulkar's last Test match for India in November 2013. It is an unusual cricket book, being both unyieldingly microscopic and sweepingly contemplative, and brimming with digressions into politics, literature and sociology. It is an account, also, of India's penchant for reverence, and of the unselfconscious way in which the country came to worship this always-dignified overachiever 'from the heartland of middleclass Maharashtra'.

D'Souza's is a tick-tock narrative which focuses chronologically on the three days of the Test against the West Indies at the Wankhede, from the very first ball, bowled by Bhuvneshwar Kumar to Chris Gayle—'who knocks it firmly away to…well, who else, for this first ball of his farewell Test? Tendulkar…'—to the last ball, bowled before lunch by Mohammad Shami on only the third day of an embarrassingly one-sided Test. Shami bowls, 'and just like that, Shannon Gabriel's middle stump is flat on the ground,' giving India victory by the sort of margin the West Indies once meted out to opponents: an innings and 126 runs.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

This book is not a love-letter to Tendulkar, who many (but not D'Souza) believe to be the finest cricketer to have played for India. It is, instead, an unsentimental but always gracious account of the last occasion Tendulkar turned out to play for his country. D'Souza writes not merely of the action on the field—the strokes, the runs, the wickets, the collapses— but also of the adulation of Tendulkar by Indian cricket fans. He is critical, and rightly so, of the way in which the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) gave Tendulkar a retirement Test that was tailored as closely as a bespoke suit of clothes to the great batsman's personal measurements.

What a borderline-sycophantic farewell it was, with the BCCI bending over double to accommodate Tendulkar with a series of two Tests 'jimmied into the regular schedule, the hand-picked venue, the mediocre opposition, the assurance of being selected for a final two Tests, the over-the-top hype.' Tendulkar retired after his two-hundredth Test, a statistical pinnacle unlikely to be scaled by another cricketer, what with the continuing devaluation of Test cricket as the currency of excellence. But D'Souza does not shy away from asking whether the Mumbaikar deserved to have been playing at all, given the frankly un- impressive form he had shown over the two previous years.

Final Test is a chastening, and occasionally rather amusing, account of how a team game can be hijacked by sentiment toward one man. Cricket has always been the least collective of all the team sports, but this last Test of Tendulkar's came to be such a brazen one-man tamasha that all the other players—and there were 21 of them—were reduced to supernumerary status. Spare a thought for poor Shivnarine Chanderpaul, the Guyanese batsman, whose one hundred and fiftieth Test match this was. No other West Indian had reached this milestone—Courtney Walsh, long retired, is the next best at 132 matches—and yet there was scarcely a public acknowledgement of Chanderpaul's feat in all the fanfare over Tendulkar.

D'Souza stops short of blaming Tendulkar himself for this unseemly overkill. The deification of "Sachiiin-Sachin"—the chant by which Indian crowds pay him obeisance—was not the cricketer's own doing. He had God-like status thrust upon him, and having had that happen, did what any other rational being would have done in his position: He retreated into a fiercely protective privacy, into the fortress of his family, and comported himself in public with a dignity and caution that added a further layer of bullet-proofing to his persona.

D'Souza is not a cricket writer by profession, and is at his best when he addresses issues that lie 'beyond the boundary'. As he describes the proceedings at the Wankhede, he dwells on the irony of the press box there being named after Balasaheb Thackeray, the Maharashtrian strongman-chauvinist who was no friend of the press, and whose followers once dug up the pitch at the ground to prevent Pakistan from playing there.

In writing about the atmosphere at the ground—the son et lumiere, as it were—D'Souza chides the BCCI, a body bloated with wealth, for treating the paying spectator with such contempt. Nothing escapes his critical eye, not even the relentless ads for 'fairness' creams that blight Indian stadiums, endorsed by cricketers who ought, he suggests, to be setting a better example. (Heartbreaking, here, is a digression in which D'Souza tells us of how he and his wife tried to adopt a child from a Mumbai adoption agency. Late in the process, he discovers that there had, in fact, been a child who was available, but had not been offered to the couple for adoption—because it was thought to be too dark-skinned.)

This is the India in which Tendulkar played. Flawed, fevered, hierarchical, complexed. D'Souza is our guide to it over three days: three days of abjectly uncompetitive cricket played before a Sachin-mad country that had eyes only for one man.