The Threat from the Tablighi Jamaat

THE GREATEST GLOBAL health catastrophe of our time has helped shine a spotlight on the role of religious evangelists and other fundamentalists in spreading the China-originating Covid-19 disease. In a number of countries, from the US and Israel to Iran and Indonesia, religious zealots—whether Christian, Jewish, Shia or Sunni—have resisted adhering to government stay-at-home orders.

In some cases, their disobedience has led to spiralling Covid-19 infection rates. In Israel, for example, Ultra-Orthodox Jews account for 12 per cent of the country's total population but as much as 60 per cent of its Covid-19 cases in major hospitals, compelling the government to start policing Ultra-Orthodox Jewish neighbourhoods in order to protect the wider population.

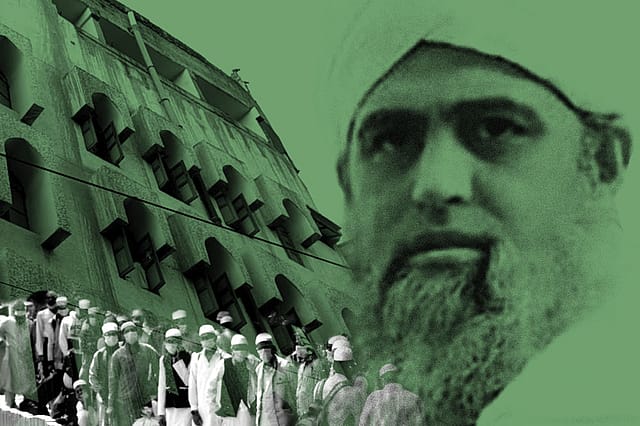

But no group has played a greater role in spreading the deadly coronavirus far and wide than the Tablighi Jamaat ('Proselytising Society'), a transnational missionary movement of the Deobandi branch of Sunni Islam that boasts more than 80 million members across the world, including in Europe and North America. It was founded in 1927 near New Delhi in Mewat, Haryana, by a prominent Deobandi cleric, Maulana Muhammad Ilyas Kandhlawi. Some commentators, not familiar with its ideology or larger goals, have presented in benign light the puritanical Tablighi Jamaat, with its wandering bands of preachers.

In truth, the Tablighi Jamaat represents a fusion of religious obscurantism, missionary zeal and an enduring commitment to global jihad—a toxic cocktail that holds long-term implications for international security and for modern democracies. Basically, the Tablighi Jamaat shuns the modern world and urges its followers to replicate the life of Muhammad and work towards creating a rule of Islam on earth.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Its revivalist and regressive ideology is espoused by radical preachers and Islamist televangelists, such as Junaid Jamshed and Tariq Jamil, both Pakistanis. The Tablighi Jamaat claims to be apolitical, but its ultimate goal—triumph in global jihad—underscores its very political mission.

To be clear, the Tablighi Jamaat itself is not a hotbed of terrorism, despite some individual acts of terror by its associates. However, the ideological indoctrination it imparts to the largely illiterate and semiliterate youths it enlists helps to create recruits for militant and terrorist outfits. It has long served as a recruiting ground for terrorist groups, ranging from Al Qaeda and the Taliban to two of its spinoffs—the Harakat ul-Mujahideen and the Harakat ul-Jihad-i-Islami. The Harakat ul-Jihad-i-Islami has proved a security challenge for India in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) and in states like Gujarat where it has taken over mosques from moderate Muslims and installed radical clerics.

A bigger challenge has been posed by the other offshoot, the Harakat ul-Mujahideen, an internationally designated terrorist organisation. Founded by the Tablighi Jamaat's Pakistan branch, the Harakat ul-Mujahideen, as the UN has put it, "was responsible for the hijacking of an Indian airliner on December 24, 1999, which resulted in the release of Masood Azhar". Azhar was not the only terrorist released from Indian jails to meet the demands of the hijackers of the IC-814 flight.

In an ignominious episode unparalleled in modern history, then Indian Foreign Minister Jaswant Singh flew to Taliban-held Kandahar to hand-deliver Azhar and two other terrorists: Omar Sheikh, a purported financier of 9/11, whose subsequent conviction for journalist Daniel Pearl's 2002 murder was recently overturned by a Pakistani court; and Mushtaq Zargar, who went on to form the Al-Umar terror group. Azhar, for his part, established the Jaish-e-Mohammed, a front organisation of Pakistan's rogue Inter-Services Intelligence agency. Just the way India's terrorists-for-Rubaiya Sayeed swap in 1989 aided Pakistan's "politico-military decision", as Benazir Bhutto put it, "to start low-intensity operations" in J&K, the Kandahar cave-in led to a qualitative escalation in crossborder terrorism.

The Tablighi Jamaat came under intense scrutiny in the US after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. "We have a significant presence of Tablighi Jamaat in the United States," the deputy chief of the FBI's international terrorism section said in 2003. "And we have found that Al Qaeda used them for recruiting now and in the past."

Alex Alexiev, the late American counterterrorism expert of Bulgarian origin, described the Tablighi Jamaat in an essay as 'wolf in sheep's clothing'. The hardcore jihadists the Tablighi Jamaat spawns in its ranks are later recruited by terrorist organisations as replacements for slain warriors. From Morocco and France to Indonesia and the Philippines, intelligence agencies and prosecutors have viewed the Tablighi Jamaat training as a stepping stone to membership in terrorist outfits. French intelligence officers, for example, called the Tablighi Jamaat the "antechamber" of violent extremism, according to a 2002 report in Le Monde.

The current pandemic, for its part, has shown how the Tablighi Jamaat's religious obscurantism, fanaticism, blinkered delusions of divine protection and open disdain for science can endanger public health and the larger social good. A prominent Tablighi Jamaat leader in Pakistan, Mufti Taqi Usmani, who is also a leading expert in sharia finance, claimed on national television that the Prophet, by coming in the dream of a Tablighi Jamaat activist, revealed "the cure for the coronavirus", which was the recitation of certain Quranic verses.

Amid the raging pandemic, the Tablighi Jamaat held ijtemas (or congregations) in several countries even after Saudi Arabia suspended the Umrah pilgrimage, Iran shut the holiest Shia sites and multiple Islamic nations closed mosques, including Jordan, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and Lebanon. Saudi Arabia, after closing off the holy cities of Mecca and Medina to foreigners, has asked the more than a million Muslims planning to perform the hajj from late July to indefinitely delay their trips, raising the possibility that the pilgrimage could be cancelled for the first time in more than 200 years.

For the Tablighi Jamaat, however, the fast-spreading coronavirus was no deterrent to staging ijtemas in several countries. Calling off any ijtema —which is an annual three-day Tablighi Jamaat congregation to help instil a sense of brotherhood and a commitment to jihad among its members—would have amounted to repudiating Allah's directive, according to Tablighi Jamaat clerics.

The Tablighi Jamaat's New Delhi-based chief, Maulana Muhammad Saad Kandhlawi, pushed innocent Tablighis into the jaws of the new disease by talking about the "healing power" of the "markaz"—the mosque-cum-dormitory complex that serves as the organisation's headquarters. Saad, the great-grandson of the Tablighi Jamaat's founder, told his followers that, in any event, the "best death" for any devout Muslim was in the markaz.

Saad's sermons that "Allah will protect us" were redolent of how Shia clerics earlier turned the holy city of Qom into Iran's Covid-19 epicentre. Indeed, Iran's outbreak of the disease began in Qom, which is visited by some 20 million pilgrims every year and where the 1979 Islamic revolution started. The ayatollahs who run the seminaries in Qom openly discounted the coronavirus risks. Mohammad Saeedi, the head of Qom's famous Fatima Masumeh shrine, released a video message calling on pilgrims to keep coming. "We consider this holy shrine to be a place of healing. That means people should come here to heal from spiritual and physical diseases," said Saeedi, who is also the representative of Iran's Supreme Leader in Qom.

The Tablighi Jamaat's ijtemas amid the pandemic unleashed the largest known viral vector in the Sunni world, spreading the disease in communities stretching from Southeast Asia to West Africa. The February 27th-March 1st ijtema of 16,000 activists at the Sri Petaling Mosque in Kuala Lumpur helped spread the disease to six Southeast Asian countries: Brunei, Cambodia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. Nearly two-thirds of coronavirus cases in Malaysia last month were linked to that ijtema.

The Kuala Lumpur gathering was followed by a much larger international ijtema at the Tablighi Jamaat's Pakistan headquarters at Raiwind, in suburban Lahore. A quarter of a million participants congregated in Raiwind on March 11th-12th before authorities privately persuaded the organisers to end the ijtema and disperse. But hundreds of participants contracted Covid-19. Within days, they spread the disease far and wide, not just within Pakistan, but also elsewhere—from Kyrgyzstan to Nigeria.

After Raiwind came the New Delhi ijtema from March 13th, although the province of Delhi (which includes New Delhi) had already declared Covid-19 an epidemic and prohibited all large events, besides shutting all schools, colleges and movie theatres. While a large throng packed New Delhi's Markaz Nizamuddin, Indonesia—in a last-minute decision—banned an ijtema in South Sulawesi just as it was about to begin on March 18th with nearly 8,800 participants. The Tablighi Jamaat initially resisted the Indonesian order but then complied by asking its activists to leave.

Despite knowing all this, including how the Kuala Lumpur ijtema helped spread Covid-19 across Southeast Asia, Indian federal and state authorities allowed the New Delhi ijtema to proceed. Maharashtra, in contrast, acted wisely by cancelling permission for an ijtema in Vasai. The New Delhi congregation stretched for 18 days until the final 2,346 holdouts were evacuated from Markaz Nizamuddin on April 1st.

Permitting this congregation has proved costly for India, including undermining the nationwide lockdown that has been in force since March 25th to combat Covid-19. Nearly a third of India's total number of Covid-19 cases has been linked to that gathering. Many contracted the coronavirus at the congregation, which they then spread to families and communities across India after returning home. Such has been the adverse fallout from the ijtema that the national lockdown is likely to be extended beyond April 14th.

The fact that many participants from other Islamic countries at the New Delhi ijtema misused tourist visas for missionary activity has also cast an unflattering light on Indian security agencies. Initial investigations suggest that some of the foreign attendees, including preachers from Indonesia and Malaysia, brought the coronavirus to the gathering.

Today, with prayer failing to keep the disease away, Markaz Nizamuddin—which Saad portrays as the most sacred place after Mecca and Medina—has been shut after being disinfected by the authorities. Saad, for his part, initially went into hiding to escape police investigations.

Looking ahead, the Tablighi Jamaat will not find it easy to repair the damage to its reputation. Long after the current pandemic is over, it will be remembered for the deaths and suffering that its ijtemas caused in many communities in the Sunni world. The ijtemas became rapid multipliers of the coronavirus.

The rancour over the Tablighi Jamaat's pandemic-related role could, in fact, exacerbate the factional infighting that has increasingly racked the organisation in recent years. The infighting largely centres on the leadership issue, with the more radical Tablighi Jamaat factions in Bangladesh, Pakistan and Britain challenging Saad's headship. The infighting has triggered even violent clashes between rival groups, resulting in multiple deaths.

Such violence has been recurrent in Bangladesh, which hosts the Tablighi Jamaat's Bishwa Ijtema (Global Congregation), supposedly the second-largest annual gathering of Sunni Muslims after the hajj. Bishwa Ijtema is held usually in January along the river Turag in Tongi, just outside Dhaka. The Tablighi Jamaat in Bangladesh, however, has split into two groups, with the more militant, anti-Saad faction supported by radical clerics and the hardline Islamist outfit Hefazat-e-Islam.

This faction, by staging a violent demonstration, forced Saad last year to return to New Delhi without joining the Bishwa Ijtema. At present, Saad's followers are not allowed into the Tablighi Jamaat's Bangladesh headquarters—the Kakrail Mosque in Dhaka.

In Pakistan, the longstanding military-mullah alliance, which has facilitated the military generals' use of terrorist proxies against India and Afghanistan, looks askance at the Tablighi Jamaat's global headquarters in New Delhi. Control over Islamist and terror groups is central to the generals' power at home and their regional strategy.

Not surprisingly, the generals have encouraged the Tablighi Jamaat in Pakistan to be independent of the New Delhi group. The Tablighi Jamaat in Pakistan maintains close ties with the generals, at whose behest it allows state-sponsored terrorist groups to enlist some of its best students for military training. Such transfer of students usually takes place at the Tablighi Jamaat centre in Raiwind, where the organisation's star recruits receive four months of special missionary training.

The generals' backing, however, has not protected the Tablighi Jamaat in Pakistan from attacks by jihadist groups that are outside the control of the military establishment. Several prominent Deobandi/Tablighi Jamaat clerics have been assassinated, including by the Pakistani Taliban—the Pakistan military's nemesis.

Maintaining state control over clerics is also the reason Saudi Arabia does not allow the Tablighi Jamaat to operate in the kingdom. A transnational Islamist movement headquartered in a non-Muslim country runs counter to the Saudi policy of keeping the religious establishment on a tight leash and using it to bankroll fundamentalist groups elsewhere.

Against this background, India's indulgent act in letting the Tablighi Jamaat hold its ijtema in New Delhi, despite pandemic-related state curbs, has stuck out like a sore thumb. National Security Advisor Ajit Doval's widely publicised meeting with Saad in the early hours of March 29th, to get the holdouts in Markaz Nizamuddin to leave, could weaken Saad's hand in the factional infighting.

More fundamentally, it is past time for India to recognise the threat from the Tablighi Jamaat's regressive ideology. That ideology is antithetical to secularism and democracy, including religious tolerance and separation of church and state. The Tablighi Jamaat, by not recognising national borders, also challenges the nation-state system.

No counterterrorism strategy can ignore the intersection between religious fundamentalism and violent extremism that this movement symbolises. Terrorist groups draw sustenance from the Tablighi Jamaat's ideology of Islamic revivalism. These groups also enlist some of those that the Tablighi Jamaat trains. In a limited number of cases, Tablighi Jamaat associates have directly committed acts of terrorism, including convicted Westerners such as 'shoe bomber' Richard Reid, 'American Taliban' John Walker Lindh, 'dirty bomber' José Padilla and 'Brooklyn Bridge bomber' Lyman Harris.

The manner the Tablighi Jamaat's obscurantism and obduracy contributed to the spread of Covid-19 is just the latest reminder of the group's threat to national and international security.