The Original Game

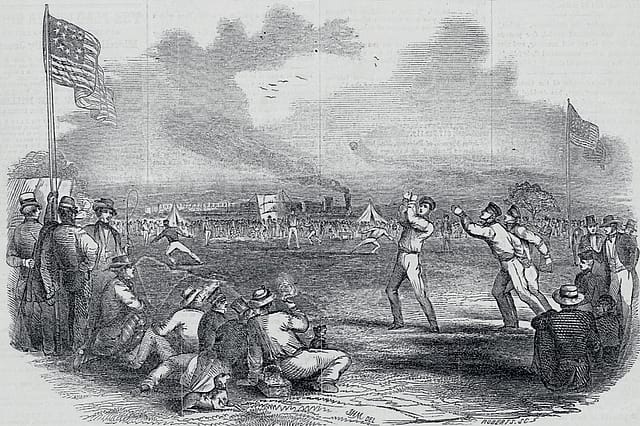

CRICKET, RECORDS indicate, remained popular in the Americas until the 1860s and the first recognised international match between Canada and the US was attended by over 10,000 spectators at Bloomingdale Park in New York in 1844. Tours to and from the US were common until the 1880s, and the best moment for US cricket came when a US side defeated the West Indies in an international match in British Guyana in 1880. Though matches between Americans and British residents were played on the American West Coast right through the 1880s and 1890s, cricket, by the turn of the century, had given way to baseball. By the end of the Civil War, baseball's ascendance to the top of the American sporting pantheon was inevitable, if not already complete. Though cricket had experienced a revival in the 1870s, it would never again compete with baseball as either a participatory or a spectator sport in the US.

The most compelling question to emerge from this development is simply "Why?" What were the factors that allowed baseball to prevail over cricket, despite the latter's longer history both inside and outside the US?

In the existing historiography that attempts to reconcile the cricket versus baseball conundrum, two interrelated themes emerge: the structure of the games themselves and the pervading cultural values of the US and other countries. Structurally, issues have tended to revolve around the time differential between baseball and cricket, the pace of play, and the spectator and player-friendliness of the two sports. Temporally, it has been explained that baseball offered a distinct advantage over cricket because it could be completed in a matter of hours, instead of days.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The difference in the pace of action between the two sports has also been emphasised. However, these barriers are not necessarily insurmountable or even valid. Melvin Adelman has in fact challenged both of these arguments in purely empirical terms. Temporally, he cites the fact that baseball teams met during two afternoons a week for practice as well as the fact that in England and in the US, artisans had found the time to play the game. In effect, it seems that at least from a participation standpoint, time was not a crucial element. Rather, it is baseball's ability to allow for a more intimate involvement of fans that is seen to stimulate its appeal. While this argument may possess a certain amount of merit in that it is factually correct, it does not help explain the popularity of cricket in other parts of the world, especially the Indian subcontinent.

Is the American sporting fan so unique as to require a more intimate view of the action? Additionally, these arguments fail to explain the enormous popularity of American football, which, when viewed live at the stadium, is notoriously "fan-unfriendly". The large field and the distant stands that characterise professional American football stadiums in the US have in no way hurt the sport's popularity, and attendance for the National Football League is healthy. Culturally, the supposed advantages of baseball over cricket become more diffuse. Cited reasons that baseball is culturally suited for the US rest on (among other things) its association with the season cycle, its trend towards extreme quantification, rural nostalgia, its ability to produce folk heroes, and as "a compensatory mechanism for the travails of industrial life", all of which are seen as something intrinsic to the American character. In trying to contend with these arguments, Jules Tygiel begins to scratch the surface of what seems to be the most compelling advantage of baseball over cricket. In labelling the preceding arguments as ahistorical, he states: "They describe values and attributes that Americans have grafted onto baseball after it became embedded in our culture."

In essence, because baseball was not established the way cricket was, it was shaped by the people who began to standardise it. It was natural that baseball would reflect the values of 19th-century America because it was forged during that era by people who held those values. Its destiny as a "national" game rested on its relative formlessness during that era compared to cricket, with its long (and foreign) history. Baseball's malleability during this time period inevitably led to it taking on "national" characteristics, a flexibility seen at the time as notable. In 1868, the American Chronicle of Sports and Pastimes claimed that baseball had changed more in 10 years than cricket had in the last 400. It also noted that this change had allowed baseball to reflect American values.

It is this question about the foreign nature of cricket that leads to the most compelling of arguments surrounding cricket and baseball. There exists a body of evidence that points to emergent American nationalism as a critical component of the battle for American sporting loyalty. American nationalism in the mid-19th century was still somewhat of a novel concept. Carl Degler has argued that the American nation emerged in part due to the Civil War, before which American nationalism was lacking. The threat of Southern secession and the potential for the US to break up less than a century after independence provided an arena where the nation was truly formed. It is therefore no surprise that an American sporting nationalism would assert itself at this time as well. Thus, the 1850s became the critical moment in this battle for sporting supremacy. As American nationalism emerged and strengthened, baseball, continually forged and moulded to suit the needs of Americans, began to assert a stronger hold on the American public, eventually pushing cricket forever into the margins of American sporting life. It was during this decade that calls for a national game were heard, and it was this decade that saw the term "national pastime" first written. The need to create a national game grew out of the American desire to "emancipate their games from foreign patterns".

Additionally, Porter's Spirit of the Times, a prominent sporting periodical of the time, demanded a game peculiar to the citizens of the US, one distinctive from the games of the British or the Germans. The New York Times also pined for the independence of American sport. Once baseball had become the unequivocal American sport, great pains were undertaken to protect its American heritage. It was this desperate need to divest baseball of its British origins that led to the creation and perpetuation of the Abner Doubleday myth surrounding baseball's creation. It began with a speech by Abraham G Mills in 1889, given in New York upon the conclusion of a baseball tour led by sporting goods magnate Albert Spalding. During the speech, Mills who was president of the National League at the time, claimed to have found definitive proof of the American origins of baseball, stating that "patriotism and research alike vindicate the claim that [baseball] is America in its origin". This claim was met quite enthusiastically by the crowd with shouts of "No rounders!"

This speech and the subsequent media support led sportswriter Henry Chadwick to defend the rounders theory, which had enjoyed popular support up until that point. Chadwick's 1903 article reasserting the English origin of the American game riled Spalding, a vehement defender of the American origins of baseball. Upon reading the article, Spalding set out to settle the issue once and for all. At his request, a special committee was formed to ascertain the true origins of the game. It included men of "high repute and undoubted knowledge of Base Ball" as well as two US senators and AG Mills. According to Seymour, "While the committee supplied the window dressing, AG Mills did what actual work was done."

After gathering evidence from a variety of sources, the committee issued its final report, the Mills Report, three years later. The report, dated December 30, 1907, affirmed the American origin of the game and officially ordained the myth of Abner Doubleday. The committee based its final report largely on the letter written by Abner Graves, who had claimed to have played baseball with Doubleday in Cooperstown. Graves claimed that Doubleday had spontaneously invented baseball in 1839. However, three central problems cropped up immediately: the Graves letter was written based on memories well over half a century old; Doubleday had never mentioned any exploits on the ball field and certainly hadn't made any claim to have invented a new game; and the fact that in 1839, Abner Doubleday was enrolled at the West Point Military Academy and did not take leave that year. It is possible that Doubleday had never even been to Cooperstown. However, the commission had spoken, and the myth was set into motion.