The Artist of the Possible

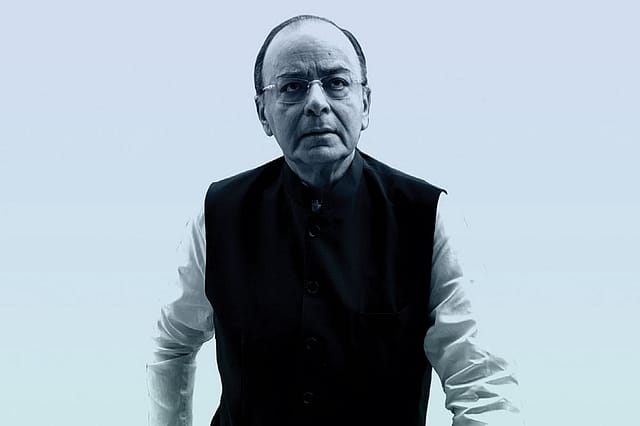

IN QUICK SUCCESSION, destiny has been unkind to a series of BJP leaders. Arun Jaitley is the latest. Several people have written obituaries about him. They touch on different facets of the man and his life. If you read them, you wonder about whether they refer to the same individual. Indeed, there were many parts to Jaitley: student leader, member of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, the Emergency era, the Jana Sangh and subsequent BJP period, successful lawyer, cricket enthusiast and administrator, the Vajpayee-Advani days and gradual buildup of the BJP, minister in the Vajpayee Government, BJP spokesperson and voice of the Opposition, formal leader of the Opposition in Parliament, minister in the first Narendra Modi Government, blogger, a media-friendly politician and a loyal friend to those who were his friends.

Inevitably, there has been much more focus on Jaitley as Finance Minister in the first Modi Government. Had health not intervened, he would almost certainly have been the finance minister in the second Modi Government. We have perceptions about a finance minister's role. After all, once every year, he/she is the face of the Government, standing up in Parliament to present the Union Government's Budget.

There is a narrow view of the Budget and there is a broad view. In the narrow view, the annual Union Budget is a statement of the Union Government's receipts and expenditure and no more. A large part of public expenditure occurs at the level of the states. There is a disproportionate amount of attention attached to the Union Government's Budget. Rather oddly, attention, including the media's, rarely focuses on state government budgets. For instance, desired public expenditure is in social sectors. There is a Seventh Schedule to the Constitution. Under the Seventh Schedule, most social sectors are either in the State List or in the Concurrent List. There has been discussion about whether the economy is in a cyclical or structural downturn. When it is diagnosed as the latter, people have come up with a list of structural reforms. If one considers that list, most structural reforms concern factor markets. Therefore, they are in the State List or the Concurrent List.

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

For the Union Government, receipts can be tax or non-tax. Non-tax receipts are primarily, though not exclusively, through privatisation. There is an important difference between disinvestment and privatisation. The second Narendra Modi Government has a list of proposed privatisation of Central Public Sector Enterprises (PSEs). Since 1991, when has there been a systematic process of privatisation, one that has been done and not merely contemplated? Memory is myopic. If we cast our minds back, we will say that the systematic privatisation exercise was during the Vajpayee Government. Unless we have read these recent obituaries carefully, we may not remember who was the disinvestment minister in the Vajpayee Government, when disinvestment became a ministry rather than a department. It was Arun Jaitley.

Our obsession with the Union Budget is because taxes changed every year. Which products have been taxed more? Which prices have gone up? This is the reason for the classic hype and secrecy traditionally associated with the Union Budget. The worst example was in 1988-1989, Narayan Dutt Tiwari's 'sindoor' Budget. In my view, tax reforms are about simplification, standardisation and stability, so that tax rates do not change on a yearly basis. That's the way tax compliance costs and tax harassment decline. This is work in progress. It is by no means the case that we have reached the ideal goal. There is resistance. Witness the way, because of the downturn, every sector clamours for special treatment. That special treatment effectively boils down to fiscal concessions. If there is special treatment for sector A, it is extremely difficult to resist special treatment for sector B. That's the way the tax structure becomes complicated. On indirect taxes, there are import duties and domestic indirect taxes. For import duties, the cleaning up started with Manmohan Singh as Finance Minister in 1991. That too is work in progress (WIP). We have not yet completed cleaning up. First, there is a basic Customs duty and there is a countervailing duty (CVD), meant to ensure that imported goods do not have an unfair advantage (safeguard and anti-dumping duties are different). CVD has to be set equal to domestic indirect taxes, provided one can clearly establish what domestic indirect taxes are. But until the indirect tax structure is cleaned up, it is difficult to establish this. Consequently, we can lose trade disputes initiated at the World Trade Organization (WTO). Second, in the absence of domestic indirect taxes being cleaned up, it is difficult to introduce a WTO-compliant system of export incentives, technically different from export subsidies, which are illegal. Third, what should be the structure of import duties? Most people will say a lower duty for raw materials, a higher one for intermediates and a still higher one for finished products. However, de facto, it is impossible to clearly determine what is raw material, what is intermediate and what a finished product is. That's the reason cleaning up import duties still remains WIP. Ideally, there should be a single import duty for all products. But, in practice, few are likely to accept this.

Let me not digress too much. Let's turn to domestic indirect taxes and the Goods and Services Tax (GST). By the same token, I think there should be only one single GST rate. There are few takers for this view. How can 'elitist' items be taxed at the same rate as items of mass consumption? In cleaning up domestic indirect taxes, we had the Value-Added Tax (VAT) and we then transited to GST. The merits of GST have been stated for one and a half decades. There are valid criticisms of GST as it stands. First, not all products are part of GST. Second, there are too many rates. Even if one does not accept the idea of a single rate, there should be no more than three rates. Third, procedures are too complicated. Fourth, since many products are in the exempted category, the Government has lost revenue. Since state governments have been guaranteed revenue compensation, through the GST Council, states have argued for more products to be moved to the exempted category. Fifth, since there is a threshold, medium and small enterprises (MSMEs) are sometimes outside the GST chain. Therefore, large enterprises find it better to import than source domestically from MSMEs. Details apart, the GST process is not as simple as it should have been. There are two ways to look at GST. In a federal structure, the Union Government cannot introduce GST unilaterally. States have to be part of the process. We could have debated for another one and a half decades, waiting for consensus on that ideal GST.

Alternatively, we recognise GST is WIP and has blemishes. However, let's introduce it and we will tweak it as we go along. The second is a pragmatic way. Many former finance ministers have claimed credit for GST. The fact remains that it was Arun Jaitley who could generate that political consensus across political parties and across Union and state Governments. The fact remains there has never been a vote in the GST Council. Even if we have complaints about GST, it will be churlish not to give credit to Arun Jaitley.

On direct taxes too, there is an agenda of simplification. That involves elimination of exemptions and without such elimination, direct tax rates (both personal income and corporate) cannot decline. This remains even more of WIP than GST. However, elimination of tax exemptions, and its link with reduction in rates, was first mentioned by Arun Jaitley in one of his Budget speeches. And it is during his tenure as Finance Minister that the Task Force on Direct Taxes, which has recently submitted its report, was set up.

I have talked about taxes. Let us move on to the Union Government expenditure. There too, we need streamlining, no annual variations. This is even more of WIP. Unlike the GST Council, we have no Union-state institutional counterpart that will evolve consensus on public expenditure, bearing in mind the Seventh Schedule. But here is some of Arun Jaitley's legacy as Finance Minister. First, the Plan versus non-Plan distinction was abolished. Second, following recommendations of the 14th Finance Commission, the untied share of states in the divisible pool of taxes was increased from 32 per cent to 42 per cent. Given the pressures on Union Government finances, this wasn't easy to implement. Third, through a Committee of Chief Ministers, there was some attempt to rationalise Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS), though recommendations fell far short of what was required. Revamp of the Central sector (100 per cent funded by the Union Government) and Centrally sponsored (part contribution by state governments) remains WIP. Lest I forget, in Jaitley's tenure as Finance Minister, there was no deviation from the fiscal consolidation agenda.

Reforms are about competition. Competition requires free entry and exit. There can't be competition with the former but without the latter. In the first Narendra Modi Government, he was also the Minister of Corporate Affairs. Before the Insolvency Code, there were no satisfactory exit provisions for unincorporated enterprises. And before the National Company Law Tribunal, errant promoters had no compulsion to exit, but could game the judicial system.

I have listed out some elements of an impressive legacy.