China’s Ticking Age Bomb

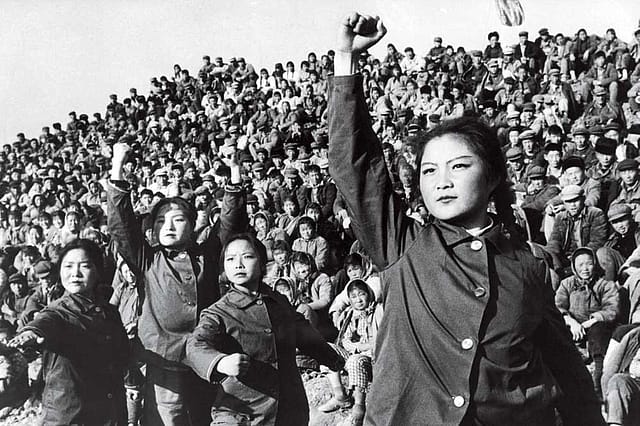

CHINA'S PRESIDENT-FOR-LIFE Xi Jinping is widely seen as the country's most powerful and ruthless leader since Mao Zedong. In a twist of fate, however, Xi now faces a blowback from one of Mao's most cherished legacies: the one-child policy.

Mao's diktat during the 1960s Cultural Revolution that left millions dead was meant to curb China's burgeoning population and reduce poverty. Nearly 50 years later, the one-child policy could stall Xi's ambition to make China the world's leading superpower in the next decade.

China is a rapidly ageing society. The median age of the Chinese population is 38.4 years. The median age of the US population is 38.1 years. The average Chinese is therefore now older, for the first time in recent history, than the average American. (The median age of the Indian population in contrast is just 28.4 years.)

This matters at several levels. As a country greys, the productivity of its economy falls. China's workforce is not only ageing, it is shrinking. The country's population has plateaued. According to estimates by the UN, India will overtake China as the world's most populous nation by 2027.

Xi was quick to recognise the danger. In 2016 he ordered an end to China's official one-child policy exactly 50 years after Mao first mandated it.

But it might be already too late. The damage has been done. Ironically, affluent young Chinese couples prefer to have just one child or none at all in line with trends in the West.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

While America's workforce remains relatively young and productive due to immigration and high fertility rates among migrants, China's ethnic insularity is an additional handicap. Not only does China discourage immigration but its brutal Sinification of Xinjiang and Tibet has led to reverse migration. China's diaspora—mostly young and educated—numbers 50 million, by far the largest of any country in the world (India's diaspora, at under 30 million, is a distant second.)

The other collateral damage an ageing society faces is rising pensions. These are financed by higher taxes. In effect, young Chinese will increasingly pay for the growing demographic 'bulge' of the elderly. Social tensions could rise as economic growth slows. China's total debt-to-GDP is 350 per cent—unsustainable in the long term.

Xi's recent actions have to be seen in the context of China's ticking age time bomb. Its crackdown on Hong Kong, military threats to Taiwan and human-rights abuses against Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang reveal a leader losing focus.

Xi's legacy project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), was designed to establish China's writ in an arc from the South Pacific to Eurasia and Africa. But beset by high debt, BRI is rapidly turning into a white elephant.

World opinion has meanwhile turned decisively against Beijing. Xi expected US President Joe Biden to be accommodating on trade and technology. But Biden has been tougher on Beijing than a blustering former US President Donald Trump.

The most telling indication of China's fall from global grace was the recent remark by the director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), Tedros Ghebreyesus, that he did not rule out the possibility the Covid-19 pandemic originating from a laboratory leak in Wuhan.

For over a year Ghebreyesus, an Ethiopian widely regarded as China's voice in WHO, had shielded Beijing from global condemnation for spreading the deadly coronavirus. His abrupt change of stance and tone is a warning to Xi.

Since he took power in 2012, Xi has bludgeoned all domestic opposition. Political rivals have been purged. Tech billionaires Jack Ma of Alibaba and Ma Huateng of Tencent, seen as future centres of power who could rally public opinion against the Chinese Communist Party, have had the ground cut from beneath their feet.

For Xi though, it's the greying of China and the ticking age bomb that poses the greatest threat to his legacy. Will it harden his posture with the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei in disputed areas of the South China Sea? When cornered, Mao lashed out at his perceived enemies. Xi, who possesses several of Mao's uncompromising traits, may do so too.

Xi's actions against India in eastern Ladakh over the past year are a grim augury. As the snow melts on the heights across the Line of Actual Control this spring, a defiant and globally reviled China could choose confrontation over conciliation.