Desmond Tutu: Why the late Archbishop of Cape Town matters after the devastation in Gaza and Ukraine

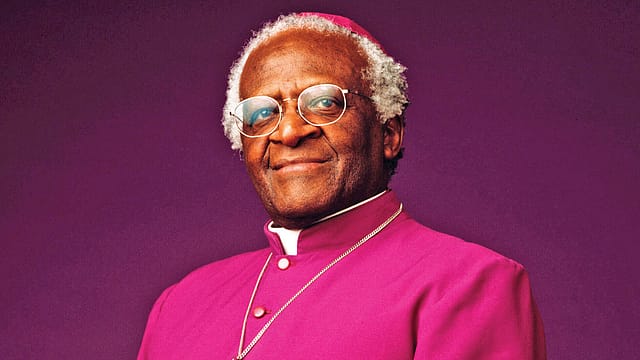

IT IS A PROFOUND HONOUR TO DELIVER the Desmond Tutu International Peace Lecture—an occasion that calls not merely for remembrance, but for moral reckoning. We gather in the shadow of deepening global polarisation, amid conflicts that fracture communities and ideologies that harden hearts. And yet, in this moment of uncertainty, we invoke the name of a man whose life was a luminous testament to the power of moral courage, prophetic witness, and radical compassion: Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu.

Desmond Tutu’s legacy is often framed by his role in dismantling apartheid—a struggle that earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984. But to confine him to that chapter alone is to miss the full breadth of his moral imagination. His fight was never only against racial injustice in South Africa; it was against every system that denied the dignity of the human person. He stood, unflinchingly, for women’s equality, for the rights of LGBTQIA+ people, for the protection of our planet, for the oppressed in Palestine, and for the poor and marginalised across the globe. His was not a selective conscience—it was a universal one. “You can change the world,” he said.

And he was universal in his causes. He once declared, “I will not worship a homophobic God.” And in that single sentence, he shattered centuries of theological complacency. He reminded us that faith, if it is to be worthy of the divine, must be expansive enough to embrace all of humanity. That it must be a force for liberation, not exclusion. That it must speak truth to power, even when power wears the robes of religious authority.

Indeed, Tutu was often ahead of the institutional church. For eight years, he campaigned tirelessly for the ordination of women as priests in the Anglican Church of Southern Africa. He did not wait for consensus; he led with conviction. And when he titled one of his books God is Not a Christian, it was not a provocation—it was a plea. A plea to recognise that the divine cannot be confined by doctrine, denomination, or dogma. That God belongs to us all, and that our humanity is bound together in ways that transcend creed.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

At the heart of Tutu’s philosophy was the African principle of ubuntu: “I am because you are.” It is a concept that defies the atomisation of modern life. It insists that our destinies are intertwined, that our flourishing depends on the flourishing of others. In a world increasingly defined by borders—physical, ideological, and emotional—ubuntu is a radical act of resistance.

Tutu’s values were not abstract ideals. They were lived convictions. He embodied forgiveness—not as a passive gesture, but as a fierce commitment to healing. He championed truth—not as a weapon, but as balm. He practised justice—not as retribution, but as restoration. And he believed, with every fibre of his being, in the inherent dignity of every human soul.

These values remain urgently relevant today. In an age of algorithmic outrage and tribal politics, we need moral courage that refuses to be silenced. In a time of ecological collapse, we need to preserve our planet with a compassion that extends to future generations. In a moment of religious strife and xenophobic conflict, we need faith that unites rather than divides.

Desmond Tutu did not merely speak these truths—he lived them. And in doing so, he left us not just a legacy, but a challenge. A challenge to reimagine coexistence. To build peace not on the absence of conflict, but on the presence of justice. To see in every stranger a reflection of ourselves.

Let us begin then, not with nostalgia, but with resolve. The resolve to carry forward the torch that Tutu lit—not as passive admirers, but as active inheritors of his moral vision. The resolve to be a “ripple” in that “tidal wave of change” he evoked.

I am an Indian Member of Parliament from the south-western state of Kerala, representing its capital, Thiruvananthapuram, for the last sixteen years. So, I was gratified to learn of an odd but pleasant connection between my constituency, Thiruvananthapuram, and Desmond Tutu. When I arrived in Cape Town, I heard from Professor Binu Luke, a medical practitioner from Thiruvananthapuram, that he is the project lead of the North-West University’s Desmond Tutu School of Medicine, which is expected to start in 2028 in Tutu’s birthplace, Klerksdorp. Dr Luke added that not only is he a doctor from Thiruvananthapuram but an Anglican to boot like the Archbishop, and a regular worshipper at the Anglican Church of Christ in my constituency.

That connection reminded me that if Archbishop Tutu taught us anything, it is that religion can be both balm and blade. Across history—and across continents—faith has been invoked to heal, and to harm. It has inspired movements of liberation, and justified systems of oppression. It has built sanctuaries of refuge, and walls of exclusion.

Today, as societies wrestle with questions of identity, belonging, and belief, religion remains a potent force. But too often, it is weaponised—used to draw boundaries rather than build bridges. We see it in the rhetoric of nationalism cloaked in religious garb. In the persecution of minorities or the defenestration of immigrants in the name of purity. In the silencing of dissent as heresy. In the conflation of divine will with political power.

And yet, Desmond Tutu’s theology offered a counternarrative. He believed that faith, at its deepest, is not about dogma; it is about dignity. Not about orthodoxy; it is about empathy. Not about exclusion; it is about embrace. Not about prejudice; it is (as he showed along with the Dalai Lama) about joy.

The “Arch” understood that peace is not merely the absence of war. It is the presence of justice, the restoration of relationship, the recognition of shared humanity. And to build such peace requires more than policy—it requires moral imagination.

What is moral imagination? It is the ability to see the world not only as it is, but as it could be. It is the courage to envision reconciliation where others see only revenge. It is the audacity to believe that enemies can become neighbours, that strangers can become kin. It is the capacity not just to sympathise but to empathise, to see ourselves in the plight of others.

In our fractured world, this imagination is in short supply. We are trained to fear difference, to retreat into echo chambers, to flatten complexity into caricature. But Tutu’s life reminds us that empathy is not weakness—it is strength. That solidarity is not surrender—it is salvation.

How, then, can societies rediscover this moral imagination?

First, by reclaiming the sacredness of the other. Tutu often said, “If you want peace, you don’t talk to your friends. You talk to your enemies.” This was not naïveté—it was prophetic realism. It was the recognition that peace cannot be built on selective compassion. That the humanity of the other is not negotiable.

Second, by cultivating spaces of encounter. Peace is not forged in isolation—it is born in relationship. In shared meals, shared stories, shared struggles. In interfaith dialogue that moves beyond tolerance to transformation. In civic spaces where disagreement is not a threat, but a gift. We live in a world where political rivals distrust and demonise each other, see each other as enemies and not just adversaries. Tutu taught us to look for the humanity in the other side and to find a space to meet it.

Third, by telling the truth. Tutu’s leadership of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was grounded in the belief that healing requires honesty. That we must name the wounds before we can bind them and heal them. That silence is complicity, and denial is violence.

And finally, by embracing vulnerability. Moral imagination is not built on certainty—it is built on humility. On the willingness to be changed by what we hear. On the courage to admit when we are wrong. On the grace to forgive, and to be forgiven.

In this moment of global reckoning, we must ask: What kind of faith will we practice? What kind of peace will we pursue? What kind of humanity will we honour?

Let us choose the path that Tutu walked. The path of radical empathy, of courageous truth-telling, of unflinching hope. Let us imagine peace—not as a distant ideal, but as a daily discipline. And let us build it, together.

If we are to reimagine coexistence in our time, we must begin with a simple but radical proposition: that the world’s faith traditions, at their deepest, are not in competition. They are in conversation.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu understood this profoundly. Though rooted in Christian theology, his moral compass was not confined to one creed. He saw in every faith tradition a reservoir of wisdom, a call to compassion, a summons to justice. He believed that the spiritual and ethical foundations of religion could be harnessed—not to divide humanity, but to unite it. That was why it was so fitting that the first Desmond Tutu Memorial Lecture was delivered by the Dalai Lama.

And indeed, across the world’s religions, we find common ground. The golden rule—“Do unto others as you would have them do unto you”—echoes in the teachings of Jesus, the Hadith of the Prophet Muhammad, the ethics of Confucius, the dharma of the Buddha, the laws of Moses, and the Upanishadic vision of the self in all beings. These are not marginal teachings. They are central. They are sacred.

I am a Hindu, and I learned from the great preacher Swami Vivekananda, who took Hinduism to the world in the late 19th century, that Hinduism stands for “both tolerance and universal acceptance. We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions as true.” As a young student of history, I had learned that tolerance was a virtue, that a tolerant king was good because he allowed you to practise a faith different from his own. But what Vivekananda taught is that tolerance is really patronising: the tolerant king is in effect saying, “I have the truth, you are in error, but I will magnanimously grant you the right to be wrong.” Whereas what Hinduism preaches is not tolerance but acceptance: “I believe I have the truth, you believe you have the truth; I will respect your truth, please respect my truth”. That is the best possible recipe for coexistence and harmony in a multi-religious world. Vivekananda often recited an ancient hymn, the Shiva Mahimna Stotram, to the effect that as different streams originating in different places all flow in different ways into the same sea, so do all paths lead to the same divinity. He repeatedly asserted the wisdom of the Hindu belief that Truth is One even if the sages call it by different names. Vivekananda’s vision was summarised in the credo sarva dharma sambhava (all religions are equal).

Yet too often, religion is reduced to boundary-making. To identity politics. To tribalism. We forget that the word “religion” itself comes from religare—to bind together. Not to bind in chains, but in kinship.

What would it mean, then, to reclaim religion not as a barrier that excludes non-believers, but as a bridge that unites those of all faiths, and none?

It would mean recognising that every faith tradition carries within it a vision of peace—not merely as the absence of violence, but as the presence of dharma, the force that maintains righteousness in the world, ensuring a universal moral order. It would mean lifting up the prophets and sages who called for justice, even when it was inconvenient. It would mean listening not only to the scriptures, but to the silences between them—the places where humility dwells.

It would mean building interfaith coalitions not just for dialogue, but for action. Action for climate justice. For refugee protection. For gender equality. For the dignity of the poor. It would mean seeing the church, the temple, the synagogue, the mosque—not as rival fortresses, but as neighbouring wells from which humanity draws its moral sustenance.

Tutu often spoke of the “rainbow people of God”—a vision not of uniformity, but of unity in diversity. He believed that difference was not a threat, but a gift. That the divine is too vast to be captured by any one tradition. That we must approach each other not with fear, but with reverence. Similarly, Hinduism has taught me that the truth is plural, that there is no one correct answer to the big questions of creation, or of the meaning of life. The greatest truth, to the Hindu, is that which accepts the existence of other truths.

This is not to deny the real tensions between religions. History is replete with conflict. But as the late United Nations Secretary-General, my boss for many years and a predecessor on this platform, Kofi Annan, put it, “the problem is never with the faith but with the faithful.” For all religions, after all, preach the virtues of peace and loving others. And the history of faith is also replete with cooperation—with shared rituals, shared fasts, shared festivals. With moments when people of different faiths stood together against tyranny, against apartheid, against genocide, or in India, against Partition.

But that is history, some will say. So must it just be relegated to the past? In our time, we must cultivate what Tutu embodied: a theology of embrace. A spirituality of solidarity. A faith that does not ask, “Who is my neighbour?” but declares, “Everyone is.”

Let us then draw from the deep wells of our traditions—not to quench only our own thirst, but to offer water to others. Let us build bridges of peace—not on the shaky foundations of tolerance, but on the solid ground of acceptance of each other, of shared moral purpose.

And let us remember, as Tutu did, that the divine is not a possession. It is a presence. A presence that calls us, again and again, to love.

Yet, even as we seek and find and express that love, we must acknowledge that to stand for peace in our time is to walk a tightrope across a landscape of contradictions.

WE LIVE IN A WORLD where the language of human rights is often spoken most fluently by those who violate them. Where the rhetoric of peace is deployed to justify war. Where the enduring of one set of horrors is cited to justify the infliction of another set of horrors. Where terrorists inflict violence on the innocent and claim to be doing so in the name of God. Where the victims of violence are judged by their geography, their religion, their colour, their strategic value. And where geopolitical interests routinely distort justice and truth.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu refused to play that game. He stood for peace—not selectively, but consistently. He spoke out against apartheid in South Africa, and against the occupation of large parts of Palestine. He condemned terrorism as a “scourge” that involved “terrible deeds of cruelty”. He condemned violence whether it came from the state or the street. He challenged injustice whether it wore the mask of ideology or the robe of religion. He did not ask whether a cause was popular—he asked whether it was just.

This moral consistency is rare. It is uncomfortable. It is costly. But it is essential. Because peace cannot be built on double standards. It cannot be sustained by silence. It cannot be negotiated in rooms where the powerful speak and the powerless are merely spoken about. Where some are actors on the global stage and the others are mere extras, shuffled about like pawns to do the others’ bidding.

To stand for peace today means asking hard questions:

• Why do some lives seem to matter more than others?

• Why are some invasions condemned and others ignored?

• Why are the rights of the rich worth so much more than the dreams of the poor?

• Why are some refugees welcomed and others turned away?

• Why are some truths amplified and others buried?

These are not, as some will allege, political questions. They are moral ones. And they demand a moral response.

Tutu understood that neutrality in the face of injustice is not virtue—it is complicity. He reminded us that silence is not peace—it is the absence of accountability. That reconciliation without truth is not healing—it is erasure.

In a world of shifting alliances and strategic interests, we must reclaim the language of peace from the calculus of power. We must insist that justice is not a bargaining chip. That human dignity is not negotiable. That truth is not relative to the interests of the strong.

This requires courage. The courage to speak when it is inconvenient. To stand with the marginalised when it is unpopular. To challenge our own governments, our own institutions, our own communities, our own political parties, and sometimes even our own religious leaders, as Desmond Tutu did.

But it also requires humility. The humility to listen to those whose pain we have ignored. To learn from those whose histories we have erased. To recognise that our moral vision is always partial, always in need of expansion.

And it requires solidarity. Not as a sentiment, let alone a slogan, but as a strategy. As a commitment to build alliances across borders, across faiths, across struggles. As a refusal to let the powerful define whose suffering counts.

This is why we need to recommit ourselves to the United Nations. As someone who served the UN for nearly three decades, from 1978 to 2007, I witnessed firsthand its evolution from a Cold War battleground to a post-Cold War laboratory of global cooperation. I was part of its efforts to protect refugees and its struggles to build peace. I saw the UN falter in Rwanda and Srebrenica, and rise to the occasion in East Timor and Namibia. I saw it struggle with bureaucracy and politics, yet persist in its mission to feed the hungry, shelter the displaced, and give voice to the voiceless. Today, when people decry its failures over Gaza and Ukraine, I acknowledge again that the UN is not perfect—nor was it ever meant to be—but it remains indispensable.

As someone who spent much of his adult life in its service, I remain convinced that the UN matters. It matters to the refugee seeking shelter, to the peacekeeper standing guard, to the diplomat negotiating a fragile truce. It matters to all of us who believe that cooperation is not weakness, and that justice is not a luxury. The United Nations remains an indispensable symbol—not of perfection, but of possibility. As Dag Hammarskjöld said, it was meant “not to take mankind to heaven, but to save humanity from hell”. In the aftermath of its 80th anniversary, its challenge is to become more representative, responsive, and resilient in a world that needs principled global cooperation more than ever. To abandon it would be to abandon the very idea of our common humanity. Our own survival and that of the only universal world organisation we have, the United Nations, depends not on nostalgia, but on renewal. And that renewal begins with the recognition that in an interconnected world, no nation is truly sovereign unless all are.

I had the great honour of meeting Desmond Tutu at the United Nations, as well as outside it. Tutu’s life was a masterclass in moral consistency. He did not flinch. He did not equivocate. He did not tailor his conscience to the times. Let us honour him not just by quoting his words, not even by echoing his ideas, but by living his witness. Let us stand for peace—not as a slogan, but as a standard. Let us speak truth—not as a weapon, but as a light. And let us remember: the arc of history does not bend on its own. It bends when we pull it—with courage, with clarity, and with love.

As we draw these reflections to a close, we must return to the crucible in which Desmond Tutu’s moral vision was most severely tested: the aftermath of apartheid.

In the wake of unspeakable violence and systemic dehumanisation, South Africa stood at a crossroads. The world expected vengeance. Many demanded it. But Tutu, entrusted with chairing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, offered something far more radical: not amnesia, not impunity, but a path through truth to justice—and through justice to healing. He understood that forgiveness is not the opposite of justice. It is its companion. That truth-telling is not a substitute for accountability—it is its foundation. That reconciliation is not a shortcut around pain—it is a journey through it.

In the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, victims were invited to speak their truth. Perpetrators were required to confess theirs. The goal was not to erase the past, but to confront it. Not to forget, but to remember rightly. Not to punish for punishment’s sake, but to restore the moral order that had been shattered.

This model has inspired post-conflict societies around the world—from Rwanda to Colombia, from Northern Ireland to Sierra Leone. And yet, the work of reconciliation remains unfinished. In many places, the wounds of war are still raw. The ghosts of colonialism still haunt its survivors and their descendants. The call for moral atonement falls on deaf ears in the countries that benefited from colonialism. The machinery of impunity still grinds on in too many places. And injustice, oppression, subjugation, genocide or terrorism all stalk too many human beings in too many places.

What does Tutu’s vision demand of us now? It demands that we reject the false choice between peace and justice. That we insist on both. That we recognise that healing requires truth, and that truth requires courage.

It demands that we listen to the silenced. That we centre the stories of survivors. That we dismantle the systems—legal, economic, ideological—that perpetuate inequality and exclusion. That we confront the perpetrators of terror, rather than sympathise with their heartless justifications. That we challenge the structures that exclude, and clamour to change them into places of inclusion.

And surely, perhaps above all, it demands that we reclaim hope—not as starry-eyed optimism, but as defiant realism. As the stubborn belief that the world can be remade, that what is wrong and unjust need not remain so in perpetuity. That the arc of history can still bend, and that it always bends toward dharma.

In a world riven by war and terrorism, by climate collapse and mass displacement, by rising authoritarianism, hostility and xenophobia, it is easy to despair. But despair is a luxury we cannot afford. As Tutu reminded us, “Hope is being able to see that there is light despite all of the darkness.”

So, let us ask: How do we cultivate a global ethic that affirms the dignity, equality, and sacredness of every person? We begin by teaching our children that no one is born to hate. That every human being carries within them the image of the divine. That our differences are not threats—they are threads in the tapestry of our shared humanity.

We continue by building institutions that reflect this ethic—schools that teach empathy, courts that uphold justice, economies that serve the common good, media that amplify truth over fear.

And we persevere by embodying this ethic in our daily lives. In how we speak. In how we listen. In how we broaden, not harden, our hearts towards those with whom we disagree. In how we show up for one another—not just in moments of crisis, but in the quiet, unseen acts of solidarity that stitch the world back together.

Let me end, then, not with a lament, but with a call to action.

Let us be the generation that refuses to be divided by fear or hatred. Let us be the citizens who speak truth even when it trembles in our throats. Let us be the believers—of every faith and none—who choose love over hatred, justice over vengeance, courage over comfort, principle over the uneasy compromises of pragmatism. Let us be the builders of bridges, the architects of inclusiveness, the healers of wounds, the promoters of hope. Let us be the ones to keep the lamps lit in the gathering gloom, the ones who hold aloft the flickering flames of hope and faith even in the midst of an intensifying darkness.

For the world does not need more cynics. It needs more Tutus, or at least more Tutu-like souls—fierce in their compassion, joyful in their resistance, relentless in their belief that peace is possible, optimistic in their determination to do their part to bring it about.

Let us begin anew. In the realisation that we are bound together.

I am because you are.

And together, we can still shape a world worthy of our children’s dreams.

I salute the blessed memory of Desmond Tutu.

(This is an edited version of the Desmond Tutu International Peace Lecture 2025 delivered by Shashi Tharoor in Cape Town on November 20.)