The Dead Do Speak

The US court summons to Kamal Nath and the Congress for the '84 riots should shame us

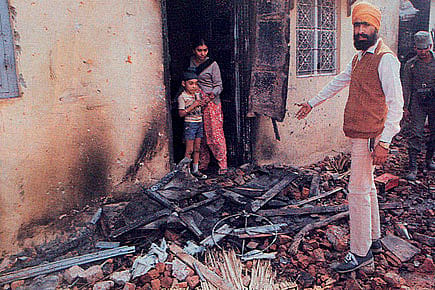

For 26 years an FIR on the death of at least 20 Sikhs in Hondh village of Rewari district in Haryana has been ignored. The survivors who moved to Ludhiana have at last dared to voice what happened in their village shortly after the assassination of Indira Gandhi. Busloads of men from outside the village came and torched their houses, burning people alive. This happened under the Congress government of Bhajan Lal, which was responsible for the humiliation and harassment of thousands of Sikhs even before the assassination.

Incidents such as this, reported and unreported, have long shadowed the Congress since 1984. The party has been unable to shake off charges of having perpetrated the massacres because it has never attempted to ensure justice was done to the victims. Leave alone a sense of remorse, leaders charged by independent commissions and by victims with leading mobs at the sites of violence were subsequently rewarded with plum posts, including positions in the Union Cabinet. The careers of men such as HKL Bhagat, Jagdish Tytler, Sajjan Kumar and most blatantly Kamal Nath are ample evidence. Kamal Nath's case especially rankles because there have been deliberate and repeated attempts to underplay his presence at the head of a mob at Rakabganj gurdwara that burnt two men to death a few hundred yards from the country's Parliament.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

Finally, hearing a class action suit, the US District Court for the southern district of New York has issued summons to the Congress and Kamal Nath for 'conspiring, aiding, abetting and carrying out organized attacks on the Sikh population of India in November 1984'. In case either fails to respond within 21 days, judgments by default will be entered.

One possible response to the summons is to invoke our national sovereignty and say that US courts neither have the jurisdiction nor the right to ask questions about events that took place in India. But that argument would have merit if the criminal justice system in India had shown the potential for delivering justice against the powerful.

In India, a judgment on the Godhra case has just been passed and 11 men have been awarded death. Valid questions on the scope of the evidence suggesting conspiracy have been raised, but at least the judicial process in the case is underway. What is striking in this context is that cases that involve the powerful largely fail to end up before the court; it is largely men such as those who have been convicted in the Godhra case who end up being arrested and charged by Indian investigating agencies.

The culpability of men in power is as much for what they did, as for what they did not do. If Kamal Nath led a mob, Modi did nothing to stop others from doing so. When men such as Narendra Modi and Kamal Nath are less hindered by the judicial process, one as a BJP chief minister, the other as a powerful Congress minister in the Central Government, when thousands of deaths in Gujarat and in Delhi go largely unpunished, what right do we have to question the jurisdiction of a US court?

In all this, there is little room for partisan reactions. We will, of course, have Narendra Modi's supporters who had raised issues of national sovereignty when he was denied a US visa now gloating over these summons. And we will undoubtedly see questions of national sovereignty being raised by Congress loyalists. This extends to the media, where political partisanship has become a way of life.

Perhaps, it is once again necessary to invoke the example of the 2G scam. It took revelations on the Radia tapes, revulsion with a cosy world that thought it ran the country without a care, for the CBI to finally gather the courage to interrogate corporate heads who had been considered untouchable in India.

If stories such as deaths in Hondh do not move us to ask questions of our government, it is difficult to see what will. Violence by the powerful and our failure to punish them is perhaps the strongest taint on our democracy. One of the strongest charges ever brought against the idea of democracy has been the possibility of majoritarian tyranny. In the labels—'BJP' and 'Congress'—that we affix on Narendra Modi and Kamal Nath, we forget that in both Gujarat and Delhi a minority was deliberately targeted, and that we as a nation have been unable to deliver justice. As long as such men remain free, as long as we lack the ability to bring them to justice, we will lack the right to question a US court, we will lack the right to claim that we have been able to give minorities the safeguards that the Constitution so admirably promises.