A War’s Best Gift

Afghanistan has a cricket team. As it aspires to enter the World Cup, a journalist remembers his encounters with players and how they learnt the sport

I saw them first in the shadow of Kabul's infamous Ghazi Stadium, where the Taliban used to execute people. A pallid dusk was falling over the dusty city, and I spotted this group of young men playing cricket. The stadium, of course, was used mainly for football matches, and the ball was kicked all around in the city and in the villages. But this was the first time I saw some people playing cricket in Afghanistan.

A day earlier, a young boy had run up to me as I waited for a local at Asad Khayil, a dun-coloured village of high-walled mud homes, dry streams, parched farms and grape orchards in the north of the country.

"Want to play cricket?" he said, gasping for breath. "I heard you [are] from India. You want me to bowl to you?"

I looked at him, bemused. The boy flicked back his Shoaib Akhtar locks and grimaced.

"I bowl fast and I bowl good. Someday you should check me out."

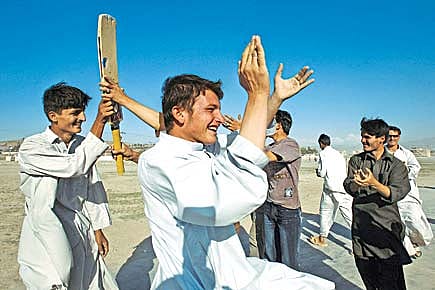

I will come another day and play with you, I told him. It was getting late, and I had to return to Kabul. Suddenly, it all began making some sense near the Ghazi Stadium. I asked my driver to take a turn in the pell-mell traffic and ended up near an unkempt garden where cricket was being played.It turned out to be a practice session for the Afghan national cricket team. They were playing on three uneven, dusty grass pitches—and aiming to reach the finals of the ongoing World Cup qualifiers in South Africa.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

It was an audacious attempt at a berth in the 2011 edition by a bunch of plucky greenhorns who believe that they are as good as many teams in the world. [At Pretoria, although their hopes were dashed by a six-wicket loss to Canada, they did score a shock win over Ireland.] Commentators in South Africa, where the recent qualifiers were played, were not calling the Afghan team the "romantics' choice" for nothing.

Where else in the world has cricket taken birth in such tragic circumstances? In a strange way, the bloody war which wreaked the country for nearly a quarter of a century helped introduce cricket in Afghanistan. Millions of refugees crossed the border into refugee camps in Pakistan after the Soviet invasion in 1979.

And Afghan cricket was born in the fetid lanes of Karha Garhi and Shamshatoo in Peshawar, where young boys played 'tapeball' cricket, cutting out wickets from tree barks or just having shoes for stumps.

When the war ended and the Soviets departed, many of the refugees returned home with the game. But when the warlords plunged the country into an internecine civil war in the mid-1990s, the refugees returned to Peshawar, and the young boys again began to hone their game, playing club cricket in the claustrophobic camps in a lawless frontier city. As I was sitting in the ochre dusk of Kabul with a bunch of unusual cricketers, the story of the birth and rise of cricket in Afghanistan unravelled.

Raees Ahmadzai, ex-captain, now "six down batsman, off-break bowler and training to be international umpire" (Afghanistan has some 30-odd registered cricket umpires), told me the story of how the cricket bug infected Afghan refugee boys as they played the game and watched it on TV to while away the desultory, hot days. "We formed the Afghan Cricket Club there with six-seven boys. Youngsters would watch India-Pakistan games on TV. Suddenly, the camps were hooked on the game," he said.

The badly wounded Soviets retreated in 1989 after a decade of futile war. Many refugees returned home, and many others remained at the camp. The cricket continued.

The Afghan Cricket Club became the champion club in Peshawar thanks to a club cricket tournament in 1993. Two years later, in 1995, Afghan authorities recognised cricket as a sport. Next year, as the country was wracked by civil war, the few refugees who had returned home again trudged back to the refugee camps of Peshawar. Three years later, the first official Afghan team travelled to Peshawar under the Taliban to play a

friendly tournament.

"If there had been no war, maybe cricket would have never come here or become popular here," one young cricketer told me.

He was possibly right. Who cared about cricket in a rugged nation of warrior men? Buzkashi—a sport in which competitors on horseback drag a dead calf over a scoreline—and football were the favourite sports; volleyball and body building had also caught on over the years. The cities are full of gymnasiums with gaudy Schwarzenegger posters. I had passed one called Youth of Asia on the way to Ghazi.

I met Abdul Shokoor, a soft-spoken wiry leg-spinner and cloth merchant. Cricket is a fickle vocation in Afghanistan. Players get a salary of around 800 afghanis (that's roughly Rs 800) a month from the government. So many of them have a second job or small business to live on. There is no other way. They have small allowances, but big dreams and big heroes.

Shokoor told me of his love for Sachin Tendulkar and Shane Warne, but his hero was the swashbuckling frontier hero Shahid Afridi. "We like players like Sehwag, Afridi, Dhoni and Gilchrist," Shokoor told me. "They hit the ball hard and they play fast."

The game was catching on like wildfire, Shokoor said. Children were playing the game anywhere—on bombed-out farms, on dirt tracks, on the sprawling mud courtyards of their homes. In Jalalabad, not very far from Pakistan and where Osama bin Laden once lived and flourished, the game was the most popular.

"We have six grounds in Jalalabad where boys play cricket there. It's a rage there," he said. It was not Jalalabad alone—cricket was now being played in at least 28 of the 34 provinces, up from just four provinces before the fall of the Taliban eight years ago. Kandahar, Logar and Khost, all restive southern provinces with a resurgent Taliban flexing its muscles, had seen an 'explosive' growth of cricket, he said.

But the Taliban, who hated most sport, appeared to have a soft spot for the game, the cricketers told me. Allah Dad Noori, who led the team under the Taliban regime, will tell you the story, they said. So I went looking for him.

I found him talking on his mobile phone, in a corner, stitching up a small business deal.

"I was luckier than most of the refugees. My father was a currency trader, so he began his business in Peshawar. We rented a place in the city, so we didn't have to live in the camps," Dad Noori said. He bought kits for his camp friends and played camp cricket. When he returned to Afghanistan after the civil war ended and the Taliban came to power, he found himself leading the team. Dad Noori told me the curious story of how a reviled, pariah regime actually supported cricket. "Mullah Rabbani (one of the founders of Taliban) was a fan of the game. He even lobbied the Asian Cricket Council to get recognition for Afghan cricket. His plea was ignored," he said. Afghanistan became an affiliate member of the ICC only after the short war and the end of Taliban rule in 2001.

Six provinces had begun playing cricket during the Taliban regime, Dad Noori said. And the Taliban men themselves were turning up to watch the dustbowl matches in the countryside. "I remember one game we were playing. A Taleb came with a gun. He watched a full day of cricket. Then he came up to us and asked if he could play too," Dad Noori said.

And what happened, I asked.

"He put down his gun, picked up the bat, and joined the game. So cricket did bring some peace too," he guffawed.

The only caveat, says Dad Noori smiling, was that games should halt during prayer time.

So when the Kandahar and Nangarhar provincial teams forgot the condition during a closely fought match in Kabul in 1997, the Taliban's vice and virtue squad turned up, stopped the match, thrashed the players and arrested a dozen of them. "The other players just ran for their lives down Kabul streets. It was quite a sight," he said.

Then adds, "All that is a thing of the past. Now we look ahead to more glories."

Today, there was no lack of pluck for the Afghan cricketers. The team has fared well in a number of international tournaments: runners-up in the Middle East Cup, beat six English second-division sides during the first tour to England. The under 15-team emerged runners-up in the Asia Cup in Dubai. Two years ago 20-year-old fast bowler Hamid Hassan became the first Afghan cricketer to turn out for the MCC at Lords.

A couple of the fast bowlers even had a stint with Dennis Lillee in Chennai.

Raees Ahmadzai reeled off the achievements breathlessly and said the time is not far away when they will take on the game's big teams. "We have great fast bowlers. They are faster than Indian fast bowlers. Hamid Hasan has clocked speeds of 145 kmph. Shahpur Zaman has clocked 140 kmph."

What about the batting?

"Don't underestimate that too," Ahmadzai said, raising a finger. "We score 230 to 240 runs in 20 overs. Mohammed Nabi hit 14 sixes in an innings against MCC. I and Nabi scored 164 runs in the last seven overs against the MCC." Ahmedzai took a deep breath and continued—the best was yet to come.

"In one match we bowled out Brunei for nine runs after scoring 375. Nine runs! We won by 364 runs. If we last out 50 overs we can score over 300 runs on any pitch."

All this took my breath away.

This is Afghanistan, after all. Two days ago, not very far away, a man dressed as a beggar had boarded a bus carrying policemen and blown himself up. Thirty-five people had died. The explosion shook the area and the shock wave from the blast had sent a friend's car, travelling a kilometer behind the bus, up in the air. But the cricketers near the Ghazi never missed practice.