One Hundred Years of Good Girlitude

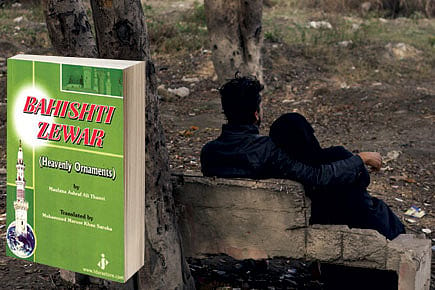

The lessons of Bahishti Zevar, advising Muslim women to defer to their husbands and never consider them their equals, are still popular with talk show hosts in Pakistan

In January, a morning talk show host in Pakistan managed to achieve something few have: evoke outrage from all sections and classes of society.

The host, Maya Khan, accompanied with a band of women and a TV crew, decided to go to a public park in Karachi, Pakistan's largest city and its former capital, and question couples why they were there, and if their parents knew what they were doing. When the programme aired, anger at Khan brewed from social media websites and newspaper op-ed pages to the streets. "Who does she think she is?" questioned Karachi's residents, while others thought they'd give her a taste of her own medicine and posted photos of her partying online.

Khan may have assumed that she could be a guardian of female morality—in her defence, she claimed she had received complaints from parents concerned about 'immoral activities'.

Over 100 years before Khan decided to investigate 'immorality', Maulana Ashraf Ali Thanvi had the same idea. A Deoband scholar, Thanvi was deeply concerned at how Hindustan's women had destroyed their faith, to the extent that this 'destruction' had spread to the world they inhabited, the children they were raising and even (one can almost imagine Thanvi gasping) their husbands. He feared that it would reach an irreversible state if someone did not step up to educate women. But Thanvi found existing literature lacking or incorrect, and so took on the task of developing a guide to serve generations of women and ensure that their children did not go astray.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

While Khan channelled her outrage into her show, Thanvi wrote a seminal book: Bahishti Zevar. His concern suff-uses this painstakingly comprehensive book, which seeks to educate the Sub-continent's Muslim women on how to conduct themselves in society and at home according to religious norms.

From matters of inheritance and divorce to health, education, prayers and the correct forms of address, or how to behave with in-laws or prepare sherbets, Thanvi covers it all in 11 chapters, in the hope that he could reverse the decay of female society.

Maya Khan was later fired from her job but Thanvi's ideas received a warmer reception—Bahishti Zevar is probably considered one of the most influential book on the Subcontinent on the role of women.

Decorated versions of Bahishti Zevar were once given to women as part of their dowry. Today, a translated version in English often surfaces on Facebook as a source of amusement, while others have deemed it 'vulgar', posting select passages online as proof. It is ironic that the arbiter of modesty has been deemed so a century later, but certain subjects covered in the book are still far too risqué to discuss in society.

Thanvi doesn't believe in evolution and this business of descending from monkeys, but he guides women through masturbation, wet dreams and the need to bathe after 'jawani ka josh' (youthful passion) has overcome them, if a hand has wandered downward (of its own accord, one wonders), or if a man has touched a woman he mistakenly thought to be his wife.

'Women should not bathe in front of other women,' he writes, but provides no explanation or context. He warns readers to maintain minimal contact with their husbands' brothers, almost acknowledging a culture in which men have lusted after their brothers' wives.

Acknowledging marital relations, he advises women that they can express affection for their husband while fasting, but 'don't lie next to him if you can't 'control' yourself'. He continues in this vein, declaring that a woman's relationship with her husband is even better than prayer: 'A husband and wife sitting together, talking of love and laughing, is better than praying.'

At other times, his tone is accusatory; he wonders aloud at double standards and scolds the reader, inducing a sense of guilt for straying away from religion.

'It is a grave mistake to consider your husband your equal,' he warns. 'After all, your husband's status is greater than your father's.'

That revelation is several hundred pages into Bahishti Zevar, but Thanvi has been leading up to it all along. Subservience, he says, is the key to a happy marriage and a woman must never complain of her lot in life, but must soldier on.

While publishers today may have asked Thanvi to footnote his edicts, he often gets away with loosely sourcing them. Elsewhere, he relies on hadeeths (sayings of Prophet Muhammad) and supplements his guidance with accounts of the Prophet's family and companions.

His need to reconnect women with religion ensures that he scrubs their lives clean of any of the traditions of the Subcontinent: do not treat a pir like a male relative, do not light lamps at graves, do not sing and dance.

But the book also accounts for Subcontinental society: while Islam considers every man and woman equal, a section on arranging marriages takes deeply-rooted norms into account and notes that some marriages beyond your clan are 'beneath your station', a claim Mrs Bennett (of Pride and Prejudice) would have endorsed. Thanvi even provides detailed instructions on the legality of marrying a wet nurse or her children and also explains if one can marry adopted children, distant relatives or an existing wife's sister.

By the end of Bahishti Zevar, female readers are left equipped to deal with everything from cardiac disorders to a husband who spends all his time with a courtesan ('bazaari aurat'), even if reading it may fill them with outrage at Thanvi's misogyny and an overwhelming need to chuck it out of the window.

Thanvi is everywhere, from the bedroom to the prayer mat, often overbearingly so. In the wardrobe, he warns women not to wear shirts made of sheer fabric; layering it with a sheer scarf is even worse. Don't be vain; don't over-douse yourself with scent. He warns women not to eavesdrop on men, interfere in discussions or share conversations had with their husbands with other women.

He is at the doorway, ensuring women don't let their scarves slip off their heads. He's in the living room, asking women to maintain purdah from eunuchs and non-Muslim women and to never let a man catch sight of one's hair, not even discarded hair teased out of a comb.

In the kitchen, he guides women on how to make soap and write down household accounts. 'This is a very useful thing because you risk forgetting if you only memorise it and then your husband doesn't trust you.'

He is there when women are writhing with pain, telling them not to overexpose themselves if they need medical attention, not even to a midwife while in labour. There's a solution for everything: if you have a boil on your leg that needs attention, wear an old pair of pyjamas and cut out a hole around the affected area. He's in the medicine cabinet too. Bahishti Zevar states that alcohol is strictly forbidden, but you can use opium et al as a medicine, as long as it is in small amounts and does not intoxicate you.

Like in clan matters, Thanvi often comes across as being flexible in adapting to society, except when it comes to obedience, a key theme in Bahishti Zevar. A guardian, be it a father or husband, is the ultimate authority (though not superior to God or Prophet Muhammad, he warns early on). If a husband tells his wife "It is night" when it is actually day, Thanvi implores her to say, "It is night" to keep peace in the house.

While even he realises that a father cannot force a daughter who has come of age into marriage, the book is laughably vague on the concept of assent. When a father tells his daughter that he has arranged her wedding and if she cries, smiles or stays silent, either of the three should be considered as a 'yes'. People who insist on a woman's clearly stated verbal assent to a marriage are out of line, he writes, although men must be vocal.

Pakistani writer and literary journal editor Ajmal Kamal, in a series of columns on the making of the 'modern maulvi', noted that Thanvi 'does not favour granting a woman the right to make the most personal decisions of her life—marriage and divorce—because in his view she is deficient in both reason and religion, and therefore in perpetual need of someone to make these decisions for her'.

While the author advises women to educate their sons and daughters, in his view, it is sufficient for women to know how to write letters and manage household accounts. According to Bahishti Zevar, being literate also improves one's social standing. The section on letter-writing includes a sample communiqué from a father to his daughter. The 'father' sternly reprimands his daughter on not taking any interest in education, and reminds her that women who cannot read are looked down upon by society for being ciphers. 'I have heard,' the imaginary father writes, 'that some women have asked 'What is the benefit of teaching girls how to read and write, they should be taught how to sew, cook and embroider. By educating them, do they want them to be maulvis like men?' But Thanvi scoffs at Western education, even counselling parents not to marry their daughters off to men with a 'Western education' who may often say things that are not in line with what religion dictates.

Thanvi's successor in guiding young Muslim women of the land is not a Deoband scholar. In Pakistan, it's a woman with a Western education—albeit a PhD in Hadith Sciences from the University of Glasgow—who is now guiding women on religion. Widely credited with having reintroduced burkhas to Karachi's young women in the 2000s, Farhat Hashmi is one of the many self-styled female instructors who offer classes in religious education and cover many of the themes in Bahishti Zevar. But while reading this book is a personal experience, Hashmi has turned religious education into a social experience by delivering lectures at the houses of her followers, drawn from the elite of Karachi, and has a well-maintained website that features her teachings.

The Hashmi model has been replicated successfully. One centre, run by an Ahle Hadith mosque, advertises: 'Come and learn what our beloved deen (religion) says, in a calm, peaceful, air-conditioned, well maintained atmosphere through educated, pious and caring Mualimat (teachers).'

Decades after the publication of Bahishti Zevar, Hashmi is serving up an MP3 version of it, along with an option to exchange family gossip. While Deobandi clerics are busy dabbling in politics, it is Hashmi who has taken on the mantle of helping women find what she sees as the right path. But given that talk show hosts like Maya Khan still feel the need to investigate immorality, perhaps Thanvi and Hashmi have failed in their noble cause.