Nehru Vs Patel: Dissimilar Disciples, Common Cause

THE PATEL VERSUS Nehru debate is as old as Free India's history. Or perhaps older. Therefore, it is only natural that every time someone wants to spite the main opposition Congress—an emaciated party which, for all practical reasons, is remote-controlled by the Nehru dynasty—the 'if Patel were Prime Minister' argument gets lapped up for political posturing more than anything else. What gets buried in this melee is the tragedy that the RSS-BJP doesn't have an icon other than Nehru's own comrade-in-arms—his deputy in the Union Cabinet, a true-blood Congressman, a leader and unifier who had publicly aired his sharp disapproval of the RSS's ways—to invoke in order to trash the legacy of the first Prime Minister of India.

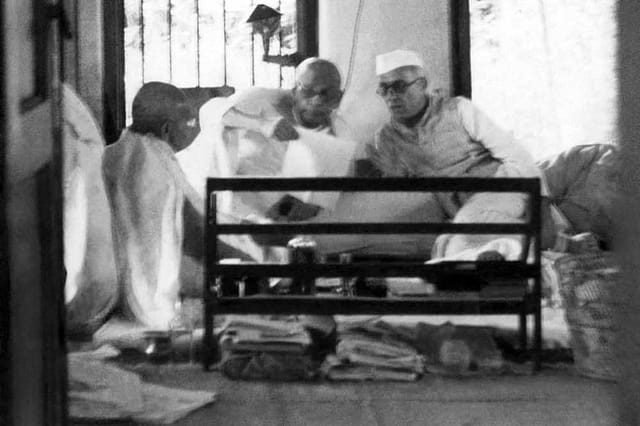

Far more than irony, the fight to appropriate Patel's legacy puts the spotlight on the Right's search for someone who could give it a piece of history that has evaded it. Nehru and Patel were rivals and they almost came to a public spat on one occasion, but many letters exchanged between the two prove that far from being locked in a mutual battle of self-interest, both these great men acted as a check on each other. Besides, despite points of friction, at the end of the day, Patel did accept Nehru as his leader.

They differed vastly in their views, but then the Congress of the time was an umbrella organisation that sheltered a constellation of views and counter-views, though there were aberrations. While Jawaharlal Nehru wanted the first Indian Governor General Chakravarti Rajagopalachari as President of India, Patel threw his weight behind a person more inclined to his views, Rajendra Prasad, who cleverly stated that he would withdraw from the race if both Nehru and Patel concurred over the question. That never happened, and Prasad became the country's first president. It is not that Rajagopalachari could be bracketed as a Nehru loyalist; rather, he was one whom Mahatma Gandhi had often looked up to as an alternative to Nehru himself. Rajaji and Nehru weren't on the same page on myriad issues, as a realignment of forces would confirm later.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

The deep differences between Patel and Nehru were also palpable when Patel backed Purushottam Das Tandon as Congress president even as Nehru pitched Acharya Kripalani, never a good friend of the Prime Minister, to take on Tandon. But Tandon won. When Patel was alive, Nehru clearly adopted a give-and-take approach and played his cards cleverly—as did Patel. It is another story that Nehru ensured that Tandon, often portrayed as a Muslim- baiter, exited nine months after Patel's death. Tandon resigned on September 10th, 1951, at an emergency high-level meeting of the Congress, which elected Nehru as the next president. The resolution was tabled in the meeting by Nehru man Govind Ballabh Pant.

Despite their ideological sparring, viewing the Patel-Nehru relationship in black-and-white terms could be a grave error for anyone in an influential position; for, that could help generate one falsehood after another in place of historical facts. Theirs was a complex relation, and both belonged to a generation whose values are incapable of being judged by contemporary political yardsticks and without a proper sense of history. Of course, as Open columnist Shashi Tharoor and several historians have pointed out earlier in their books, Nehru and Patel came to a major confrontation only over the issue of East Pakistan. There again, when Nehru challenged Patel to a public debate, the latter, despite his formidable strength in the Congress party, chose to give up and endorse Nehru's views, a confirmation that their ties cannot be properly understood without factoring in their ideas on propriety and safeguarding of political interests. Strange their friendship may have been, but it endured turbulent times both before and after freedom.

Speculative assertions and hypothetical questions like 'What if Sardar Patel had lived beyond December 1950?' or 'What if Nehru had died before Patel?' don't mean much if the intention is to fathom the depth of friendship or intensity of differences between the two. True, as Marxist scholar Perry Anderson has argued in his The Indian Ideology, Nehru, son of a wealthy man, had a sense of entitlement very early on and knew very well that he was promoting his daughter to the higher echelons of the Congress. Nehru wasn't a darling of Indian communists either, especially after the dismissal of EMS Namboodiripad's government in Kerala in 1959 over frivolous contentions, a decision that if he were alive, would surely secure full marks from Patel. In fact, their differences were far more nuanced to be left to mere politicians to gauge. They had, as new documents reveal, no differences over the use of force in many parts of the country to bring such territory under the Indian Union. The Hyderabad 'police action' of September 1948, codenamed Operation Polo, is a case in point. Recent outbursts over Kashmir also bring out the irrationality of casual assessments made about their differences, notwithstanding the personal attributes of these two individuals: one was a hedonist and the other a tireless worker.

More than anything, letters between Patel and Nehru point to mutual respect and the liberty to hit out at each other loudly or agree wholeheartedly. A celebration of that democratic spirit at the country's topmost levels during its most trying times, those fledgling years of independence, speaks of functionality rather than lack of it. Without their debates, the overall discourse would have been poorer.

The following is an excerpt from a letter Patel wrote to Gandhi about Nehru on January 13th, 1948, after having clearly pronounced their differences:

'The burden of work has become so heavy that I feel crushed under it. I now see that it would do no good to the country or to myself to carry on like this any more. It might do harm.

Jawahar is even more burdened than I. His heart is heavy with grief. Maybe I have deteriorated with age and am no more any good as a comrade to stand by him, and lighten his burden… and you have to again and again take up cudgels on my behalf. This is also intolerable to me.

In the circumstances, it will perhaps be good for me and for the country if you now let me go. I cannot do otherwise than I am doing….'

Nehru's reply to Patel (to the letter to Gandhi which was copied to him as well) was delayed by the assassination of Gandhi by Nathuram Godse.

Nehru replied finally to Patel on February 3rd, 1948:

'…Now, with Bapu's death, everything is changed and we have to face a different and more difficult world. The old controversies have ceased to have much significance and it seems to me that the urgent need of the hour is for all of us to function as closely and cooperatively as possible. Indeed, there is no other way.

I have been greatly distressed by the persistence of whispers and rumours about you and me, magnifying out of all proportion any difference we may have. This has spread to foreign ambassadors and foreign correspondents; mischief-makers take advantage of this and add to it. Even the Services are affected and this is bad. We must put an end to this mischief.

It is over a quarter of a century since we have been closely associated with one another and we have faced many storms and perils together. I can say with full honesty that during this period my affection and regard for you have grown, and I do not think anything can happen to lessen this. Even our differences have brought out the far greater points of agreement between us and the respect we bear to each other. We have even agreed to differ and yet carry on together.

I had hoped to have a long chat with you, but we are so terribly pressed for time that we can hardly see each other in private for long… such talks are necessary from time to time. But meanwhile, I do not want to wait for this talk and hence this letter, which carries with it my affection and friendship for you.'

As soon as he received the letter, Patel wrote back to Nehru, on February 5th, 1948:

'I am deeply touched, indeed overwhelmed, by the affection and warmth of you letter of 3 February. I fully and heartily reciprocate the sentiment you have so feelingly expressed.

We have both been life-long comrades in a common cause. The paramount interests of our country and our mutual love and regard, transcending such differences of outlook and temperament as existed, have held us together. Both of us have stuck passionately to our respective points of view or methods of work; still we have always sustained a unity of heart which has stood many a stress and strain and which has enabled us to function jointly both in the Congress and in the government.

… I agree with you that we must find more time for mutual consultations so that we can keep each other informed of, and in touch with, what is happening and we can thus resolve any points of difference that might arise.

We should also find an early opportunity to have a long talk and clear our mind of any doubts and difficulties that may be there. Continued harping on our differences in public or private is bad for us, bad for the Services and bad for the country. The sooner we set this at rest once for all and clear the murky atmosphere the better.'

Among the letters they would exchange over the next many months, at a time when Patel had already had a heart attack and then cancer in the stomach, both communicated on issues of differences, spelling out each of them clearly and opening their hearts out to protest and at times rail against each other (of course, in their own temperate ways). Their letters touched upon the military option in East Pakistan, quibbles over who did what in the bureaucracy and the need to keep the Cabinet in the loop on crucial decisions, among other issues. The letters offer an insight into the forthrightness of our topmost leaders of the Independence generation. In the case of Nehru and Patel, their combination seems to have ushered in—for at least several decades—political ethics that upheld democratic values as well as the consolidation of India's newly won freedom.

After Patel's death aged 76, Nehru displayed extreme shrewdness and dexterity in reining in his rivals within the Congress and the Cabinet; yet he remained a democrat in the sense of not letting the country slip into a dictatorial mode. For him, the persona of being a true democrat in the global scheme of things was paramount and his ambition to be recognised as a global statesman was evident. He also contributed immensely to the building of institutions in the country and their effective running. Would Patel have succeeded in containing socialism in India is another 'what if' that can be raised. While it is difficult to offer an answer, Nehru, with his quasi-socialist policies and progressive sounding speeches, was able to resist a movement that would have otherwise shaped up into a national phenomenon. Surely, the religion- obsessed political legacy of Gandhi also contributed greatly to the weakening of socialist movements in the country.

Patel was a pragmatist, a doer, and he certainly deserves credit for warning Nehru, a dreamer and a romantic who made several big mistakes to go with his stellar contributions to parliamentary democracy in the early years of our fragile freedom, about the intentions of the Chinese. Distraught about India's naive policy towards China, a country that had historically been a hard nut to crack for multiple colonial empires, Patel wrote a letter to Nehru a month before his death in November, 1950. Nothing could be more prophetic.

'… I am, however, giving below some of the problems which, in my opinion, require early solution and around which we have to build our administrative or military policies and measures to implement them.

a) A military and intelligence appreciation of the Chinese threat to India both on the frontier and to internal security.

b) An examination of military position and such redisposition of our forces as might be necessary, particularly with the idea of guarding important routes or areas which are likely to be the subject of dispute.

c) An appraisement of the strength of our forces and, if necessary, reconsideration of our retrenchment plans for the Army in the light of the new threat.

d) A long-term consideration of our defence needs. My own feeling is that, unless we assure our supplies of arms, ammunition and armour, we would be making our defence perpetually weak and we would not be able to stand up to the double threat of difficulties both from the west and north-west and north and north-east.

e) The question of China's entry into the UN. In view of the rebuff that China has given us and the method it has followed in dealing with Tibet, I am doubtful whether we can advocate its claim any longer. There would probably be a threat in the UN virtually to outlaw China, in view of its active participation in the Korean War. We must determine our attitude on this question also.'

If—and that is a big if—Patel had been alive to complement Nehru in his foreign-policy ventures in the decade ahead, especially when Chinese intransigence and the Indian position became too wide for comfort, perhaps things would have been different. But then again, perhaps not.

Most importantly, any disregard of facts needs to be called out. Instead of highlighting the Nehru-Patel differences, the current crop of politicians cutting across party lines could learn a lesson or two on how to disagree with respect and put the country's interests before their own.

Related stories