The Whole Hague

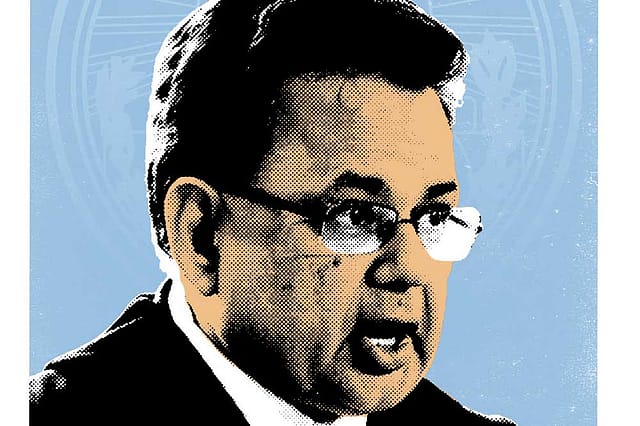

THE TEMPERATURE HAS been taken. And the UK—if it wasn’t clear so far—has been found ill. For the first time in the history of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the country will not have a judge sitting at the court. In its place will be Justice Dalveer Bhandari, the Jodhpur-born Padma Bhushan-conferred former Indian Supreme Court judge whose term as the ICJ judge was otherwise coming to an end in February next year.

The five permanent members of the UN Security Council, which includes the UK, have had a vice-like grip on power throughout the history of the organisation. Their power isn’t just limited to within the Council. They ensure that their nominees are elected to all key UN offices. There is a convention, for instance, that each of the five members will have a sitting judge at the ICJ. There has been only one exception until now, from 1967 till 1985, when there was no Chinese judge. The remaining 10 seats are shared by the rest of the world, usually allocated in this manner: three seats to the Asia Pacific region, three to Africa, two to Latin America and the Caribbean, two seats to Eastern Europe and five seats to Western Europe and others.

Five judges, from India, the UK, Brazil, France and Somalia, were up for re-election this year. And until recently, it was speculated that except for India, whose judge would have to compete with Lebanon’s Nawaf Salam, all the others would be re-elected. But after five rounds of voting, four judges from Brazil, France, Somalia and Lebanon got elected, leaving two serving candidates Bhandari and the UK’s Christopher Greenwood to compete for the only spot. Greenwood had the majority in the Security Council and Bhandari in the General Assembly. Another six rounds of elections took place, but the deadlock continued.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

To both the UK and India, this appears to have become, among other things, a prestige battle. For the UK, to show that it still matters in the world. And for India, to assert its presence in what it believes is an altered geopolitical landscape, and in the process also allowing it to gauge the true value of its many strategic tie-ups. Among other things, Bhandari’s election would also mean he would be part of the ICJ bench adjudicating the case of Kulbhushan Jadhav, the Indian national sentenced to death by a Pakistani military tribunal.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, the two countries no doubt stepped up their diplomatic efforts. According to media reports, India pushed the line that Bhandari had won the majority but was being kept out by the elite at the Security Council. Lobbying from India, these reports say, was taking place at the highest levels, with Narendra Modi and Sushma Swaraj bringing up the matter at diplomatic interactions. India apparently also created a separate cell, headed by a joint secretary, to coordinate the campaign within the External Affairs Ministry.

There was talk that a joint conference between representatives of the Security Council and General Assembly could take place. But the UK withdrew its candidate, saying, “The current deadlock is unlikely to be broken by further rounds of voting.”

For post-Brexit Britain, India will be an important trade ally. And such an impasse would probably hurt. Greenwood’s withdrawal letter among other things made it a point to cite the UK and India’s ‘close ties’. And the UK’s Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson told the House of Commons, “As the House will know, a long-standing objective of UK foreign policy has been to support India in the United Nations.”

The election was of course not about who among the two was the better judge. Perhaps like all such elections at the world body, it was about the importance of ties, about diplomatic pull and push, jockeying and lobbying, and the altering power-equations in a fast-changing world.