Karur Stampede: Trial by Tragedy

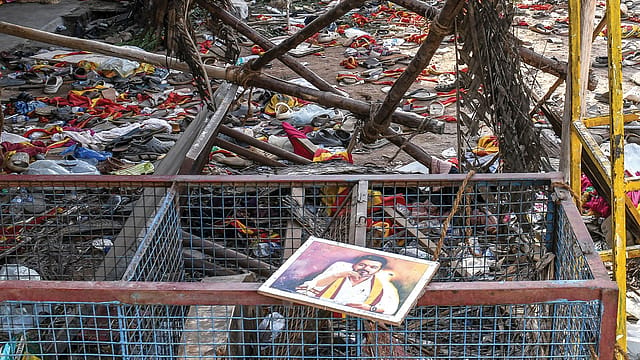

THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT BEFELL actor-politician Vijay’s rally on September 27, killing 41 and injuring dozens in Karur, Tamil Nadu, is still being unpicked, but some facts are indelible. Permissions were granted for far fewer than the 25,000 (police estimates) to 60,000 who turned up. The actor’s arrival was rescheduled, and even as his caravan idled, the restless crowd surged forward. Barricades were bent and the stampede was sudden, brutal and uncontainable as the crowd folded in on itself.

The FIR charges Vijay’s closest lieutenants with culpable homicide not amounting to murder, accusing them of negligence, endangerment and disobedience. Vijay is not named, but his abandoning the scene and issuing a condolence post hours later has done no favours to his image. While both the ruling Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and the main opposition party All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) initially refrained from taking potshots at the actor, there is an unshakeable sense that the dead in Karur might become part of a campaign against the new political experiment launched by Vijay which may have suffered a serious setback.

The debate that rolls across the state is: Was Vijay the victim of a conspiracy, trapped by rivals eager to blunt his rise? Was he made a scapegoat by a state government eager to shield itself from its own lapses in crowd control? Or was this precisely proof that being a celebrity is not a guarantee of being fit for leadership? Every possibility has its chorus, its evidence and insinuations. But what no one disputes is that Karur is the hinge. Tamil politics, crowded with strongmen and dynasts, has been waiting for Vijay, the star who can match DMK and AIADMK for street power, the only other figure besides Rajinikanth to inspire persistent speculation. Rajini retreated before even beginning. Kamal Haasan remains stranded as an ineffective political presence. Vijay, by contrast, had seemed serious, disciplined, cautious: he built a party from his fan network and duly invoked Periyar—minus the atheism—and Ambedkar too, declaring himself a lion who would not bow to either DMK or the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). At his party’s Madurai conference held on August 21, he told a crowd that the 2026 election would be a “direct fight”, his party against the ruling DMK, no alliance, no compromise.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

But weeks later, in Karur, the gap between performance and presence was exposed when Vijay returned to Chennai even as the town reeled under the tragedy. “My heart is shattered. I am writhing in unbearable, indescribable pain and sorrow that words cannot express. I extend my deepest condolences and sympathies to the families of my dear brothers and sisters who lost their lives in Karur. I pray for the swift recovery of those receiving treatment in the hospital,” he later wrote, the words a poor substitute for his absence at Karur Government Medical College and Hospital, which DMK and opposition leaders have since visited to meet the injured and bereaved families.

Long before Karur or active politics, Vijay had been staging politics in another medium. Cinema was his rehearsal hall. For two decades, his screen roles built a template of the rebel, the conscience-keeper, the man who stands against corruption, corporate greed, state neglect, the man who would not only fight but also explain, in set-piece monologues, why the contest mattered. In Thamizhan (2002), he played a law student who rails against injustice in the courts. In Kaththi (2014), he doubled as farmer and imposter, standing against a corporate land grab. In Mersal (2017) he carried his anger into healthcare, a doctor raging at corruption in hospitals and government. Sarkar (2018) was almost pure politics: a businessman returns to Chennai to cast his vote, finds it stolen, and launches a crusade against the system; by the climax, Vijay is exhorting citizens to reclaim democracy. To say Vijay was preparing for politics is to state the obvious. By the late 2010s, it was not just his fans who saw the inevitability; political analysts noted how carefully Vijay was embedding political thought into popular cinema.

Off-screen, the scaffolding was being laid. His fan clubs, the Vijay Makkal Iyakkam, initially organised around film releases and birthday celebrations, evolved into service organisations, organising blood donation camps, relief work during floods and cyclones and welfare drives. When the official announcement of TVK came in February 2024, Vijay arrived with an archive of speeches that his followers already knew by heart, with a political lexicon borrowed from not just his roles but also Tamil history. The question still is not whether Vijay can summon a crowd but if the gatherings translate into votes that alter Tamil Nadu’s entrenched bipolar map.

At the party’s conference in Madurai held in August, the stadium was filled to the brim, a show of strength meant to answer doubters. Vijay carried himself as though AIADMK’s decline and BJP’s perceived irrelevance in the state had left only him as the counterweight to the DMK political machine.

“He thought he could show his power and strength through large crowds, which backfired with his third meeting. Vijay can at best split a small fraction of DMK votes as he is targeting the anti-BJP and Dalit votes. But in reality he is not a presence on the ground,” says an AIADMK source. AIADMK, led by Edappadi K Palanisamy, incidentally conducted a rally at the same place in Karur, Velusamypuram, a day before the ill-fated event. Palanisamy, who has not ruled out an alliance with TVK, refrained from hitting out against the actor, preferring to blame the state government for an alleged lack of sufficient crowd control measures, a charge the MK Stalin administration has denied.

In striking contrast to AIADMK’s alliance politics, the clarity of Vijay’s positioning has been hard to miss. A few days ago, in Namakkal, on his first foray into the Kongu belt in western Tamil Nadu, he told supporters “A vote for DMK in the 2026 Assembly election is a vote for the BJP,” and accused the AIADMK of “inappropriate and opportunistic” ties with the saffron party. He vowed that TVK “will never make any compromises with the fascist BJP regime,” keeping both DMK and BJP in his crosshairs, the former as its political enemy and the latter its ideological foe.

Some political observers have drawn parallels with the late Captain Vijayakanth, whose Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam (DMDK) polled nearly 8 per cent in 2006, climbing to 11 per cent in 2009, before allying with Jayalalithaa’s AIADMK in 2011 and briefly leading the opposition with 29 seats. But the party’s dependence on alliances eroded its identity and it collapsed once the honeymoon ended. More recently, Kamal Haasan’s Manitha Needhi Maiyam (MNM) and Seeman’s Naam Tamilar Katchi (NTK) have collected between two and seven per cent of votes, enough to spoil margins but not sufficient to claim power. Vijay is entering at peak stardom, unlike Vijayakanth in 2005, but the precedent is sobering: Tamil Nadu’s third fronts often rise quickly, then plateau or get absorbed.

Raveendran Doraiswamy, a political commentator, insists Vijay is “untested, unproven, at zero per cent with a registered party,” dismissing him as an “arasiyal viyapar (political trader)” lacking an ideological core. “He is self-centred and an introvert, and therefore ineligible to lead people. Votes that were veering towards Vijay will now be mopped up by NTK,” Doraiswamy says. Other observers have pointed to the thinness of policy detail in speeches. There were broad strokes—clean governance, women’s safety, rejection of dynastic corruption—but little by way of specifics. No manifesto, no articulation of how TVK would govern a state of 80 million.

Still, Vijay’s ability to command attention is valuable currency. He is the rare figure who can draw youth in droves, rally villages as well as cities, and some believe, split the vote in the northern districts like his predecessor Vijayakanth did. But now, Karur is testing Vijay in a way that no film has. Politics in Tamil Nadu has always turned on such moments. DMK and AIADMK have endured calamities, corruption charges, splits and betrayals but their cadres and institutional heft allowed them to absorb the jolts. Vijay, who once supported Jayalalithaa in her campaign for power—“like a squirrel” according to his father—leading to the nickname anil (Tamil for squirrel) being given to Vijay fans, is now the man who came late to his rally and took no accountability for the tragedy. Some of Vijay’s supporters have suggested a political conspiracy, arguing the state moved with uncharacteristic speed to “frame” TVK while dragging its feet on other tragedies. The reason for the sudden alacrity, they say, is because the government saw in Vijay a genuine threat.

Vijay’s popularity remains, but the Karur incident complicates his politics, perhaps irrecoverably. Tamil politics has a way of testing leaders by fire. Karunanidhi survived the dismissal of his governments and the splits in his party. Jayalalithaa endured corruption charges and even jail and returned more powerful. MGR himself faced mutinies, illness, and controversies. In each case, survival depended not on avoiding crisis but on absorbing it, transfiguring it into strength. If Vijay can own Karur, apologise, reorganise TVK, then it could become his initiation.

His most recent release, The Greatest of All Time (GOAT), in September last year, came across like a farewell tour stitched into genre clichés. The announcement that his next, Jana Naayagan, would be his final outing is a strategic signal that he intends full commitment to politics. Vijay’s timing, entering at a moment when DMK and AIADMK are both vulnerable to anti-incumbency sentiment and generational churn, gives him a window. But elections are built and won on booth committees, polling agents and candidate networks. Can TVK deploy viable candidates in 234 seats? Can it provide the financing, backrooms, alliances, and local leadership to sustain year-round politics? It remains to be seen.