Lisbeth Salander and Literary Vampirism

The rule is that there are no good translators; there are only butchers who write like dilletantes, and dilletantes who dip their pens in eau de cologne

—Jean-Paul Sartre

The words of a dead man are modified in the guts of the living

—WH Auden

Lisbeth Salander is still alive and kicking ass in the gritty underbelly of Stockholm. Or is she?

As thriller buffs across the world know, Lisbeth is the fiercely combative heroine, a sort of geek-goth latter-day Modesty Blaise, of Stieg Larsson's Millennium Trilogy, the international bestselling series that was published after the death of the author.

Some claimed that Larsson's work lacked the literary quality and psychological complexity of Henning Mankell's Kurt Wallander books about the ageing, diabetic detective who, even as he explores the world of violent crime, is assailed by intimations of his own mortality. But such carping criticisms were drowned out by the ringing of cash registers as Larsson topped the charts of global bestsellers and became the most neon-lit name in the increasingly modish genre of Scandinavian noire.

When last seen, in the final book of the Millennium Trilogy, The Girl Who Played With Fire, Lisbeth was acquitted of a framed murder charge, with the help of Mikael Blomkvist, the uncompromising investigative journalist of Millennium magazine, and exposed a high-level political conspiracy hatched by an inner circle of the Swedish secret police, Sapo.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

With Larsson dead, that seemed the end of the line for Lisbeth, much to the dismay of her countless fans, whose already formidable numbers swelled following the making of not one but two movie versions of the first book of the Trilogy, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo.

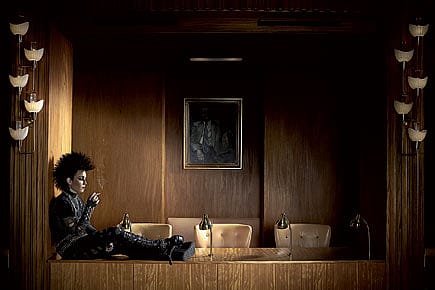

But going by the publishing world's marketing mantra that nothing succeeds like reincarnated success, a born- again Lisbeth has made a comeback, along with Larsson's other Millennium characters, in David Lagercrantz's The Girl in the Spider's Web. This time round, the fearless heroine in her punk outfit of black metal-studded leather and her genius-grade computer hacking skills gets herself enmeshed, together with Blomkvist, in a tangled web of transnational corporate skullduggery centred around computer scientist Frans Balder who is the world's leading expert on the emergent technology of AI, or Artificial Intelligence.

Fearing for his life, and of that of his eight-year-old son, August, an autistic mathematical prodigy, Balder contacts Blomkvist, who goes to meet him in the midst of a raging Stockholm snowstorm only to find that the scientist has been fatally shot only moments earlier. In the meantime, Lisbeth has through a different route got involved in the case.

With her passionate commitment to fighting injustice and protecting the vulnerable—a response honed by her own abused childhood, and the brutality of her sadistic father, a Soviet defector who was protected by a top-secret clique within Sapo—Lisbeth rescues August literally from under the gunsights of a deadly assassin and plunges into the Darknet, the secret digital layer that lies below the Net, to take on a ruthless gang of cyber-criminals led by the enigmatic Thanos and with clandestine connections to both the American National Security Agency and the Russian Duma.

At stake is not only her own life, and that of August, but also the incalculable implications, both in economic and bio-philosophical terms, that Artificial Intelligence has for the destiny of civilisation, when machines can far out-think humans.

The well-executed action scenes are leavened with thought-provoking ethical and moral insights into the cutting-edge realm of AI. 'Computers will start enhancing themselves at an accelerating pace… and become a hundred, a thousand, ten thousand times cleverer than we are… how do you think a computer would feel when it wakes up to find itself … controlled by primitive little creatures like us. Why should it put up with that?… The risk is that everything we know about the world will cease to be relevant, and it'll be the end of human existence.'

Lagercrantz is an acclaimed Swedish writer and crime journalist, and he makes a valiant attempt to fill the shoes of Larsson. But, like all those who attempt sequels and follow in the footsteps of other authors, he is handicapped by a disadvantage inherent in such spin-offs.

Sequels are a form of resuscitation, but instead of achieving a living resurrection, more often than not all that such acts of literary vampirism do is give rise to revenants, a tribe of walking undead, who while looking and even sounding like the originals lack the lifetide of blood, the pulse beneath the skin, that animated the originals from whom they have been cloned.

Adrian Conan Doyle, Arthur Conan Doyle's son, tried to replicate Sherlock Holmes but succeeded only in mummifying the sleuth and turning him into a Madame Tussauds effigy. Kingsley Amis and Sebastian Faulks, both notable writers, managed to produce, respectively in Colonel Sun and Quantum of Solace, a James Bond who at best rated 0061/2 out of 007.

Despite such cautionary tales, sequels continue to be in vogue. A copycat Hercule Poirot exploit, The Monogram Murders by Sophie Hannah, has just been released. Also in the pipeline is another Holmes, written by Anthony Horowitz with an as yet undisclosed title, and Faulks has been commissioned to ring for PG Wodehouse's 'gentleman's personal gentleman' in the forthcoming Jeeves and the Wedding Bells. Devotees of the celestial Plum will be heard muttering "Hell's bells!" in rejoinder to such sacrilege.

Lagercrantz has just about managed to pull it off in his first Millennium outing. But he would be well advised not to essay a follow-up which Lisbeth fans might dismiss as 'The Girl Who Created a Storm in a Teacup'.

(Jug Suraiya is a writer and columnist)