How love and compassion survived Partition

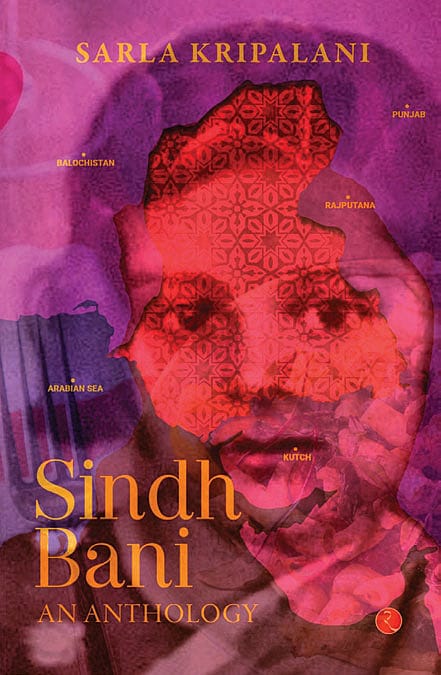

THERE ARE BOOKS that chronicle history, and there are books that resurrect it. Sindh Bani by Sarla Kripalani— brought to life anew by her daughter Manjeet Kripalani—is one such act of resurrection. It is less an anthology and more a threnody, a tapestry of memory spun from a land that exists now only in longing.

Before Partition, Sindh was a civilisation of confluence. A place where the Indus flowed like a sermon, where Sufi fakirs sang beside Sikh saints, where Hindu merchants prayed at both temples and dargahs, where Bhakti and Sufism blended into one melody of devotion. Sindhis were never defined by dogma; they were merchants of compassion and carriers of culture. And when Partition cleaved the land, they became merchants once more—this time of memory, rebuilding the world from exile and enterprise.

Sarla Kripalani, born in Karachi in 1930, now deceased, writes as both witness and wanderer. Her Sindh Bani begins with recollections of a childhood gilded with affection and shaded with loss. We meet Dewan Dialmal Doulatram, who foresaw Partition long before it came; we wander through fragrant banknotes, family feuds, the laughter of friends, the tears of farewells. These stories recall the Sindh that thrived before it was torn apart.

The book’s second movement is a bridge—‘Aaya Pir, Bhagga Mir and Other Sindhi Proverbs’—a bilingual bouquet of wit and wisdom. Each proverb gleams with the distilled intelligence of a people who survived without land yet never lost language. Here, one senses the rhythm of a civilisation that saw the divine in humour and humility alike. The Sindhi tongue stands as metaphor for what the Sindhi spirit has always done: translate loss into laughter, distance into dialogue.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The final section, Sarla’s translation of TK Mirchandani’s work on the Sindhworki apprenticeship system, reveals the other side of the diaspora’s glittering success—the toil of young boys sent abroad by the Sethias, trading childhood for commerce, innocence for ambition. Their stories are the unsung footnotes of global Sindhi prosperity.

But what makes Sindh Bani remarkable is not nostalgia alone, it is continuity. By publishing her late mother’s words, Manjeet Kripalani transforms remembrance into renewal. A daughter editing her mother’s voice is itself an act of cultural inheritance, a gesture that mirrors the Sindhi condition: nothing owned, yet everything carried forward.

Across the world, the Sindhi diaspora has done precisely that. From LK Advani to Ram Jethmalani, from the Hinduja family to Lata Krishnan in Silicon Valley, from the Tulsianis of Hong Kong to the Harilelas of Kowloon, Sindhis have rebuilt not just their fortunes but their faith in life itself. They are cosmopolitans with

caravan hearts, businesspeople with bhajan souls.

Sarla’s prose glows with the radiance of that spirit. She is gentle, unsentimental, and deeply human. Through her eyes, the reader glimpses a world where embroidery and education, prayer and play, were all acts of art. In her Sindh, even the dust was sacred, because it held the footprints of many faiths walking side by side.

Sindh Bani is not just the story of a province lost—it is the anthem of a people who refused to vanish. It reminds us that identity is not geography but grace, not possession but persistence. The Sindhis, rendered homeless in 1947, turned migration into mastery. They made the world their Sindh—building homes, schools, temples, and fortunes wherever they went, but never ceasing to sing of the river that once bound them.

To read Sindh Bani is to hear that song again: of water and wanderers, of exile and endurance, of mothers and daughters who kept faith with memory. And in that song lies a quiet revelation—that what was lost in Partition was land, but what survived was love. The Sindh that still sings is not on any map. It beats within the Sindhi heart.