Air Pollution: Breathing Death

DELHI-BASED ENTREPRENEUR AND former politician Yasmin Kidwai says that, a few months ago, she almost died. In November 2025, she stopped breathing for a while in what she felt was an “extremely traumatic” experience brought on by the Delhi smog—a thick blanket of poisonous particles floating in the moist, cold winter air. It was this “near-death episode” that set her thinking: isn’t it time that I move away from the national capital for at least three months in a year when the air pollution in the city rises to unimaginably high levels in winter? “I am still working on it although my plan has reached nowhere yet. That is the time kids come home from college. That is when I get busy with business activities. What do I do with my pets? What about my other priorities? I am still contemplating how to make it happen. We can’t live and work like this in Delhi forever,” she states.

Kidwai says she tries to stay indoors in the winter months from November to January, unless it is urgent for her to be present in person, to avoid yet another “frosty embrace of death”. Similarly, Rachel, a Germany-based MNC executive who resides in South Delhi, notes that she either works mostly from home during these winter months or plans holidays during the period, if it is possible. Then she warns, “Unless you have your air purifiers on in all your rooms, from my experience, indoor air pollution is no different compared with the high Air Quality Index [AQI] levels outside.”

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

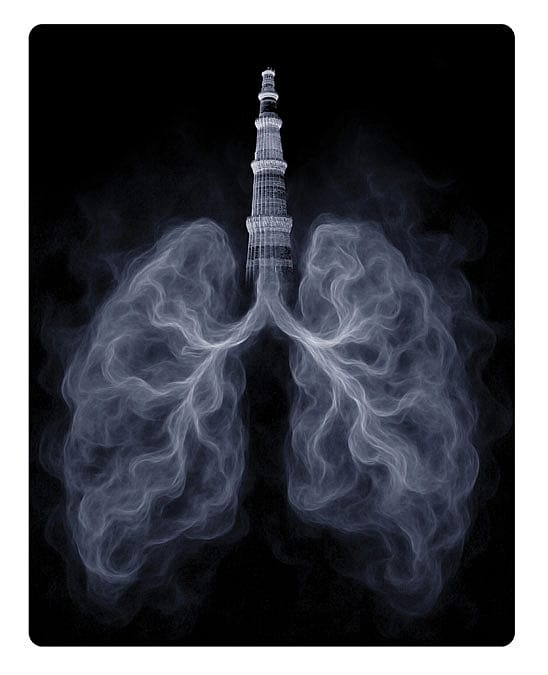

These experiences corroborate the shocking numbers published in the Delhi Statistical Handbook 2025 released on January 8, 2026, by the Directorate of Economics & Statistics and the Office of the Chief Registrar of the Government of NCT of Delhi. Deaths recorded in Delhi from respiratory diseases in 2024 stand at 9,211; the figure was 8,801 a year earlier and 7,432 in 2022, confirming a steady rise in respiratory and non-respiratory disease caused by air pollution indiscriminately claiming lives. Effectively, for Delhi, air pollution has become the modern Grim Reaper.

In the midst of uninformed comments from people occupying positions of power casting doubts about the health hazards of air pollution, especially in the face of scientific evidence to the contrary, Swati Kumar (name changed), a senior TV anchor, tells Open about her worries of continuing to live in Delhi—as well as about raising her son in the city: “A typical day starts with getting up with a headache every morning. For kids, it’s the worst. School holidays for a month or online classes don’t suit everyone. For kids like my son who have problems with social interactions, frequent school closure only adds to his woes.” She shares that the private school her son attends provides air purifiers but, strangely, teachers dislike them being placed in the classrooms because “they have this idea that classrooms are meant to stay open, not shut”. “I am finding it increasingly difficult to focus on work or get good sleep because of bad AQI. The outcomes are predictable: sore throat, groggy eyes,” she notes, adding that all this means using eye drops at least five times a day to look presentable on TV.

Kumar states that those lovely memories of winter mornings in Delhi’s famous parks Sunder Nursery and Lodhi Garden are gone. She and her husband have decided not to invest in a home in Delhi-NCR. “I have been travelling to other cities quite often. I feel a stark difference and a rise in energy and greater focus while I am elsewhere, especially in smaller towns,” she says.

Jyotika Rawat, a 26-year-old fitness enthusiast and coach from Delhi and a former professional boxer, has heard stories of children bearing the brunt of Delhi’s air pollution. What she confronts on a daily basis is a wall of smog dampening her efforts

to stay in shape by running. “I have been trying to improve my running capacity and achieve new goals to cover the distance of 5km. But in winter months, I am invariably behind the record I set for myself in the better months of summer, notwithstanding the heat. The whole thing leaves me exhausted, too, in winter, which is why I have shifted to running on the treadmill, which is not where I prefer to run,” she says.

Listed so far are troubles of the well-heeled who have the option of staying back home in the comfort of their purified homes although they need to step out and do work occasionally, and often on an optional basis, driving around in air-purified vehicles.

ON THE OTHER hand, for the poor, polluted air is not an inconvenience but an unavoidable occupational hazard that hurts health, shortens lives and reinforces inequality as a general failure of the system, which is quietly outsourced to private consumption.

As one of the fastest-growing major economies in the world, India was destined to face the problem of air pollution amidst a marked spike in vehicular emissions, industrial activity, dust caused by rampant construction—besides, of course, seasonal stubble burning by farmers in states close to the national capital. But policymakers, pulmonologists and experts state that we could also replicate plans successfully implemented by other countries and cities that had been through similar situations and had managed to reduce air pollution to viable levels through strict regulations, promotion of public transport, and a raft of other measures to save lives.

Now, the problem at hand isn’t limited to Delhi or other major cities or trade hubs alone, but other locations as well. Across the country, 1.7 million people died in 2022 due to exposure to PM2.5, an ultra-fine particulate pollutant, according to a report by The Lancet. The report, titled ‘The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change’ and released on October 29, 2025, cited more than 1,718,000 deaths attributable to anthropogenic air pollution (PM2.5) in 2022 in India, an increase of 38 per cent since 2010. It added that fossil fuels, such as coal and liquid gas, were responsible for 7,52,000 deaths, accounting for 44 per cent of the total. According to the report, coal alone caused 3,94,000 deaths. It also dwelt on vehicular pollution and toxic gases like nitrogen oxides and carbon monoxide. In 2022, the report said, the economic loss from premature deaths caused by outdoor air pollution was $339.4 billion in India, equivalent to 9.5 per cent of the country’s GDP. The report also talked about rising heat and indoor pollution besides cooking fuels that cause a major spike in mortalities in the countryside.

Policymakers and health experts say particles of size less than 5 microns are a major airborne concern and a health hazard, and these fine particles (PM2.5) deeply penetrate lungs and pose health risks by reaching deep lung tissue or even the bloodstream.

Dr Paramez Ayyappath, a noted pulmonologist who has worked in several North Indian cities, including Delhi, Ajmer and Jaipur, agrees that air pollution in India is not limited to Delhi alone although the situation in the national capital is inching from bad to worse each passing year. Delhi gets all the attention, he agrees, but adds that air pollution is a major concern in Kochi, too, a city where he is based currently. He attributes such phenomena to industrial pollution. Ayyappath, senior consultant of Pulmonology Division & Critical Care Medicine at Lisie Hospital in Kochi, says studies from Kerala have shown the irreversible nature of damage to the human body, especially lungs, on exposure to certain kinds of air pollution. “Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) following a massive fire at the Brahmapuram waste dumping yard in the state showed that the damage was not reversible, although the bias in the study was that we did not have the data for the tests before the exposure,” he says. Yet, data from people who were young and non-smokers showed substantive damage to lungs, even months after exposure. Ayyappath had previously worked at Delhi Indraprastha Apollo Hospital, Fortis Escorts Heart Institute, and others. He also said that cancers caused by air pollution have to be classified as non-respiratory illnesses linked to the menace.

Senior Delhi-based pulmonologists as well as some government officials agree that tourism to India may also be affected because of the failures of state and Central governments to adequately address the threat. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified several health risks and vaccination recommendations for travellers to India, according to reports.

According to various studies and disclosures by doctors, some of the most common respiratory health conditions due to air pollution in India are asthma, pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Children and the elderly with a propensity for lung infection are at extreme risk of air pollution. Ayyappath adds that air pollution of the type prevalent in India and other North Indian cities across Uttar Pradesh and Haryana that figure on the top 10 list of most polluted cities can cause damage to a baby while it is still in the womb. “Premature deliveries, abnormalities, malignancies and cardiovascular complications are also caused by air pollution—not just asthma, pneumonia and upper and lower respiratory diseases,” Ayyappath stresses. In fact, several studies have pointed out the dangers of air pollution in India for foetuses. For instance, a report was published in The Lancet Planetary Health in December 2024 about the effect of PM2.5 exposure and mortality in India. An article on the official website of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health quoted a co-author of that study, Dr Joel Schwartz, as saying, “We found that every 10 microgram per cubic metre increase in PM2.5 concentration led to an 8.6 percent increase in mortality.” Schwartz, a faculty member in the Department of Environmental Health at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, went on, “The increase was even larger for 10 microgram per cubic metre increases in PM2.5 from levels below the Indian guidelines of 40 micrograms per cubic metre… Delhi may get the headlines, but this is a problem all over India, and nationwide efforts are needed. Coal burning electric plants need scrubbers, crop burning needs to be limited, and most importantly, the government needs to recognise this as a major issue.”

Hyderabad-based Dr Raghavendra Reddy, a pulmonologist, says that it is not just fine particles that are causing major respiratory and other illness linked to air pollution, but a mix of pollutants, from PM2.5 to nitric oxide to carbon monoxide to hydrogen sulphide to a cocktail of others, he notes, adding that it is affecting infants and the healthy population, leaving them with long-term health problems. He says that exposure to air pollutants also exacerbates any existing health condition because the inflammation caused by previous infections makes a patient more vulnerable to health problems than before. “Your common cold has become longer than before. Similarly, all kinds of illnesses get worsened because of the damage caused to your body by air pollution,” he says, emphasising that people end up becoming hypersensitive to a range of allergens and irritants, significantly expanding a patient’s propensity to develop various health conditions. Reddy warns against policymakers being in denial, stating that a simple PFT test of a young man or a woman in a place hit badly by air pollution versus in a remote Indian location where the air is breathable is enough to prove the ill-effects of breathing polluted air. He calls for a comprehensive survey to establish the real extent of the health scourge. Reddy notes that while coastal cities have the advantage of flushing polluted air out of the city thanks to strong sea breezes, Delhi being a landlocked city is at a disadvantage.

Now, let’s return to the class angle of the air pollution problem. Instead of solving the crisis created by mismanaged consumerism and growth, the administration appears to be looking the other way as private players jump in to promote further consumerism. As of now, what is happening in India is that the market, especially in air pollution-hit North India, is flooded with air purifiers by companies of all sizes from various continents as urban Indian homes and offices rush to purify indoor air. Lately, a few entrepreneurs seeking to strike it rich have started businesses to install centralised air purifiers (like centralised air-conditioners). Car purifiers too are selling out at great speed, as are “mobile air purifiers” that one must wear around the neck. Effectively, business enthusiasm is replacing state apathy. This has led to the poor, who cannot afford air purifiers, being hit the worst as the authorities fail to fix the fundamental problem of air pollution through regulations and a raft of other measures successfully tried in many parts of the world, including big cities such as Beijing and New York.

The disaster is at our doorstep and the time to act was yesterday. Nothing less than a Herculean effort is now required to pull us back from the brink.