Weird Indian Jobs

Presenting seven Indian jobs that you would not have believed existed.

They photograph the dead, check the stitching of cricket balls, hand a token to the driver of a moving train, use myths to challenge beliefs of a corporate culture, move around the country updating maps, record the history of families, physically change tram tracks to keep them on their course—these are jobs that do not belong in an office, jobs that are nobody's ambition because they are beyond our imagination.

Photographer of the Dead

The glass-covered wooden shelves inside 63-year-old Bilal Nisar's studio near the Burning Ghats of Varanasi are lined with pictures of people—some postcard size, others blown-up like posters—all dead.

It was in 1966 that Nisar first understood the profit potential of clicking photos of the dead. He was paid Rs 150 for taking shots of a dead neighbour. Nisar says he felt "odd" receiving money for capturing such a picture, but an unusual business plan was born that day. And more than four decades later, he has reached an understanding with himself. "It is work, and whether the person is dead or alive does not matter. When I click the dead, I do it as an art. After all, it is the last time the family will get a chance to be photographed with that person," says Nisar.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Since Hindus believe that one can attain moksha (salvation) by dying in Varanasi (formerly known as Kashi), large numbers of people come to this city to die, and the belief ensures that fires never go out on the ghat (river bank). Nisar's studio never shuts either. One of his effective sales techniques is to simply ask, "Need a photo?" to relatives carrying bodies past his studio. Few say no. Many even see it as the last wish of the deceased party's soul.

Nisar approaches his subjects just as aesthetically as photographers of the living. He lines up the women (only male members are allowed on the cremation ghat) and directs them to hold the body in various poses. As soon as he's done shooting the grim scene, Nisar sprints back to his studio. "It takes about three hours for a body to burn. By that time, the photographs are ready," he says. A postcard-size photo is priced at Rs 60, 4×6 size is for Rs 90, 5×7 is for Rs 120 and 8×10 comes at Rs 225. All photographs are in digital colour and given in triplicate. — Haima Deshpande

The Pointsman

Ismail has been a pointsman for over five years, as an employee of Indian Railways. He is a 21st century man doing a 19th century job. Ismail is an essential part of an old signalling system that requires a pointsman to hand over a token to the train driver, to ensure that it is safe for the latter to continue the journey on that track. To do his job, Ismail has to stand precariously close to a moving train, on the edge of the railway platform—his arm stretched out holding a cane ring with a metal ball attached to it. He makes a split-second connection with a man inside the train, which could be travelling at 100 kmph. Roukdi Station—situated between Miraj and Kolhapur in southwest Maharashtra—is one of the few places in the country that still uses this system. It was introduced by the British in stations situated along single-line railway tracks. This mechanical system is mostly redundant now, with most stations switching to electronic systems instead. Ismail is happy for change to come his way. He says several times he's been smacked in the face by errant tokens flung by drivers. "Some people do it on purpose." — Ritesh Uttamchandani

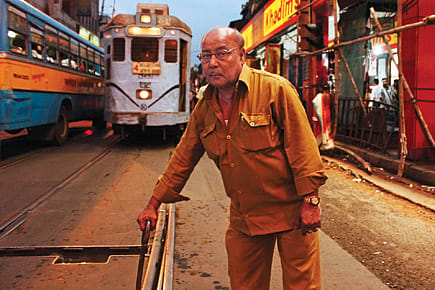

The Traffic Cleaner

The Calcutta Tramways Company calls Akhtar Hussain a traffic-cleaner. It does not accurately describe what Hussain does: he is responsible for changing the tracks of a tram so that the vehicle keeps to its designated course. Hussain has executed this responsibility for 30 years now. He spends his days standing at various street intersections in Kolkata, waiting to hear the bell of a nearing tram.

Trams were first introduced to Kolkata in February 1873. Today, Calcutta Tramways Company puts 170 tramcars on 68 km of tracks everyday. There are 119 different points where tracks have to be changed. And many of them—especially places where tracks run through the middle of busy thoroughfares—are dangerous. Hussain pushes the rails with a steel rod to send the tram down the correct route.

It's a hazardous job. "Many of us have been knocked down by speeding vehicles when we step on the roads to change tracks. I suffered a fractured leg after being hit by a vehicle some years ago. Many have died as well," he says. And for this monotonous but crucial activity, Hussain earns Rs 15,000 a month.

He is now posted at the Hatibagan crossing in north Kolkata. His day starts at 4 am—for the first tram that rolls out of the depot 15 minutes later. He's on duty till noon, which marks the end of the first shift. Until he begins again the next day. — Jaideep Mazumdar

The Map Maker

Jay Kumar is a cartographer. His occupation is neither odd, nor specific to India. But the challenges he faces while doing his job as a surveyor are very peculiar to this country. Kumar is general manager, projects, at MapmyIndia, a company that provides navigation system solutions. MapmyIndia was the first to map many parts of the country, way before Google Maps got there.

MapmyIndia has charted 1.7 million km in India. Around 400 surveyors walk or drive through the country to update their maps. But mapping India can be a dangerous and frustrating exercise. There are no rules or systems that operate the same way in two places. For instance, Mumbai is building-oriented, while Delhi is marked by colonies. And there's no information, from whatever source, that can be completely trusted. As Kumar found out when his team set out to map Uttarakhand. "We just had a Survey of India map, which wasn't detailed. What was shown as a straight road would turn out to be zigzag, 400 km would in reality be 500 km." Then there's the problem of names. Every cartographic system expects a road name. In India, roads either don't have a name or have far too many. Cadell Road in Mumbai is known in five ways; Kochi is known as Kochi, Cochin and Ernakulam.

India is also landmark-driven. But some landmarks like Dhaula Kuan in Delhi don't exist anymore, while others change too often. Surveyors are also expected to note physical attributes like road width, dividers, manholes and sometimes even the circumference of trees or the number of barbers in an area—if the client demands it.

Cartography is also particularly dangerous in India. Cartographers, or surveyors, have been mistaken for municipal officials and terrorists. Over the years, Kumar has picked up several lessons, such as: always alert the local police in advance and secure their permission. It avoids the unnecessary arrest of team-members. — Shubhangi Swarup

The Ball Inspector

No one grows up dreaming of being a cricket ball inspector. Yet, the designation exists wherever cricket balls are made. Without the oversight of inspectors, a defective cricket ball could find its way to an international game, and who knows what would happen then.

At 61, Wasi Khan, chief ball inspector at the Sanspareils Greenlands (SG) factory in Meerut, has scrutinised cricket balls for nearly half his life. Kailash Anand, proprietor of SG, knew Khan from their playing days when they were in college. In 1982, Anand invited him to join SG as a cricket specialist. Bored with his assignment as a clerk at State Bank of India, Khan accepted.

Until recently, Khan inspected each Test-quality ball personally. This meant looking at 425 balls over two-and-a-half hours every day. He studied the lacquer coating for blemishes, the lip (where the two halves are joined), size, and stitches across the seam. "Now there are boys who do this for me," he says. "I check what they have approved, and notice they still make mistakes. It should take them another two years to get it completely right." Once in a while, he pops into the inspection room to show how a master does it: against the daylight coming through a window, he turns the ball slowly, waiting for a defect to reveal itself. If something's wrong with a ball, it is tossed into the pile meant for school and club cricket. The best ones get to play international cricket.

For the last 15 years, SG has supplied balls to the BCCI for international cricket. If an SG ball does not last as long as it should, the Board informs his company. Complaints come directly to Khan. That is not a happy position, but he says all he can do is what he's been doing all along.

The technique SG employs to create balls is also dependent on variables like leather quality, but Khan says it's unlikely that errant balls can slip through the quality dragnet. He knows the process inside out, and can tell you things like why producing balls with a less prominent seam needs threads made of nylon, not linen-cotton. It is this knowledge that he hopes to pass on before he moves from SG in two years. "I'm losing interest now," he says, "I'd like someone younger to take over. But they don't let me go." — Rahul Bhatia

Chief Belief Officer

His visiting card states his designation as Chief Belief Officer, but what is Devdutt Pattanaik's place in the Future Group's corporate structure? "I challenge your belief. I tell you where your belief is coming from. I tell you where your belief is going. I use various methods to do it. I show them, 'This is your belief. Is this the way you want to continue?'," he says.

After graduation, Pattanaik worked in marketing, sales, and as an executive assistant for 14 years. He grew popular for his lectures on mythology, and wrote books and a column on the subject. One reader of his newspaper columns, Kishore Biyani, offered him a job. In 2008, he joined Future Group and began spreading the light.

Pattanaik uses mythology to show employees an Indian way of thinking. So how does he apply it to management? "Do you know Vishnu?" he asks. "What are the things he holds?"

I don't remember.

"About 80 per cent of your readers know it. Your vision is limited… In his hands are a conch shell, wheel, mace, and lotus. Shankh is about communication. Chakra is about rhythm and regularity. Mace is about discipline. Lotus is something you give people when you appreciate them. Now look at what management does. You have to communicate, review, punish and discipline, and reward. If you do this rhythmically, your company will grow," he elaborates.

Pattanaik handles his image carefully. His website features a video called The Making of Devdutt… His pictures are what he wants them to be, his voice is even, and his smile, unsettlingly constant. The only time it breaks is when I ask him, "How do you convince people that…" He interrupts to remind me that as Chief Belief Officer, he does not convince people, he converses with them. "If they take something out of our conversations, good. But if they don't, that is up to them." — Rahul Bhatia

Community Genealogist

Forty seven-year-old Nemichand Bhat is a genealogist. In Rajasthan, a Bhat maintains the records of over 2,000 families, tracing their ancestral roots back some 300 years. Nemichand's father and grandfather were genealogists, as were their forefathers. The Bhat records births, marriages, stories and memories, helping each generation of the family maintain a sense of identity.

It's an important task in a place like Rajasthan, where few things are as important as exclusivity of caste and community. "If anyone marries outside his community," Nemichand Bhat says gravely, "then he will be disinherited. Naturally, I will have to cut out his name from the family tree." So, every time a marriage proposal is mooted, the family goes into a huddle with their Bhat, who then traces the bride or groom's antecedents.

"A Bhat must have a prodigious memory and orderly mind, so that he can devise an efficient filing system," says Nemichand. A Bhat travels about 200 days of the year; the remaining period at home, he makes detailed entries in the Book. For his labours, a successful Bhat like Nemichand makes about Rs 8,000 a month, besides gifts in kind. While it is the men who practise the profession, female family members help by duplicating the Book.

Nemichand Bhat was a young boy when he accompanied his father on his rounds. After a brief stint at the village primary school, he adopted his family's hereditary profession, and found that he enjoyed the nomadic nature of the job. He is confident his art will never die, because human beings will always want to know who they are, and where they come from. — Mini Chandran Kurian (The writer is the author of Folk Yatra)